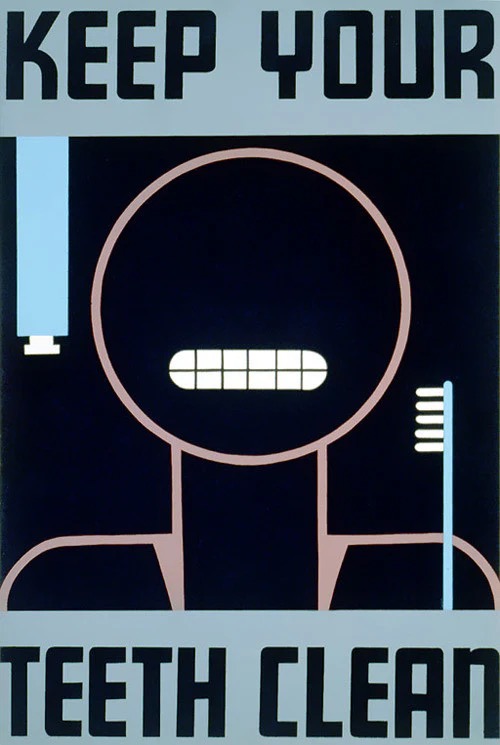

Two of my favorite books this year were not about comics specifically but about the larger visual culture in which comics emerged during the first half of the American 20th Century. Christopher Long’s overview of commercial graphic ideas, Modern Americanness: The New Graphic Design in the United States 1890–1940 takes us from the poster art craze of the 1890s to the streamlining motif that flourished in late 1930s graphic storytelling. And Ennis Carter’s Posters for the People: Art of the WPA reproduces nearly 500 of the best posters from the New Deal-funded Federal Art Project of the 1930s. Between the two books we peer into a comics-adjacent history of commercial art and how it was incorporating design ideas that expressed the experience of modernity and absorbed some of the artistic concepts of formal modernist art. Although neither book mentions cartooning per se, their subjects are engaged in the same cultural project as cartoonists – to find visual languages that capture and often assuage the dislocations of modern change.

Continue readingTag Archives: painting

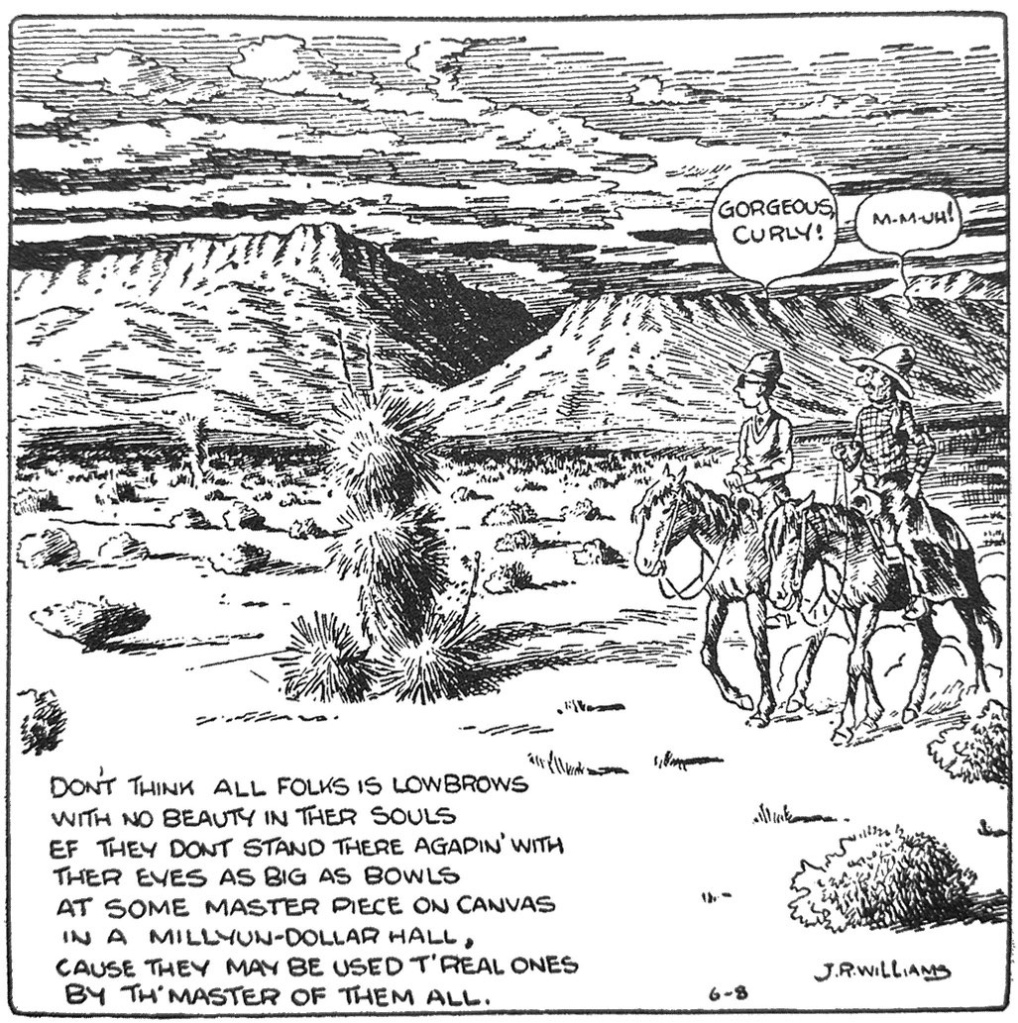

Cartooning the ‘American Scene’: Comics as Modern Landscape

We are such suckers for highbrow validation. Sure, we pop culture critics and comics historians talk a good game about bringing serious critical scrutiny to popular arts, our respect for the common culture…yadda, yadda. But our pants moisten whenever the intelligentsia deign to take our favorite arts seriously, or we find some occasional reference or connection between the “high” and “low” culture labels that we claim to disown. Comic strip histories love to gush over Cliff Sterrett’s appropriation of Cubist stylings in Polly and Her Pals. Although his dalliance with cartooning was brief, Lyonel Feininger’s Expressionist turn in the Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie loom so large in comics history you would think he was a beloved mainstay of the Sunday pages. In face, he was a fleeting presence. Picasso’s devotion to the Little Jimmy strip suggests somehow that Jimmy Swinnerton was onto something deeper than it seemed. And of course the critical embrace of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat started early, when Gilbert Seldes and e.e. Cummings, among others, primed us to believe the greatest of all comics for its surreal aesthetic and mythopoeic narrative.1 Never mind that the strip suffered limited distribution and perhaps narrower audience appeal. Indeed, an entire scholarly anthology, Comics and Modernism is a recent map of all the ways in which comics studies tries to wrap the “low” comic arts in the (to my mind) ill-fitting coat of high modernism.2

Continue readingGasoline Alley’s Emotional Realism

Frank King’s Gasoline Alley may be the “Great American Novel” of the 20th Century we didn’t know we had. This remarkable multi-generational saga of the Wallets evolved in several panels a day across decades, exploring the domestic and emotional lives of small town Americans during a century of intense change. And in its heyday during the post-WWI era, this strip was singular in its affectionate embrace of suburban family life at a time when post-war disenchantment overwhelmed the intellectual class, when glamour, sex and emotion dominated the film arts and magazines and glitz dominated Hollywood. When more famous social commentators like H.L. Mencken, Walter Lippman and Sinclair Lewis lampooned, decried and doubted the small town American intellect – the so-called “revolt from the village” – King celebrated what Mencken called the “booboisie.” Comics historians often characterize the post-1915 period of the medium as a kind of literal and figurative domestication. As newspaper syndication expanded into every burg, the mass media business of comics needed to shave the edges off of a once-raucous and urban-focused art form. Shifting the focus to family relations and suburbia, relying on more repartee than prankish violence, made the comic strip more acceptable to a mass audience.

Continue reading