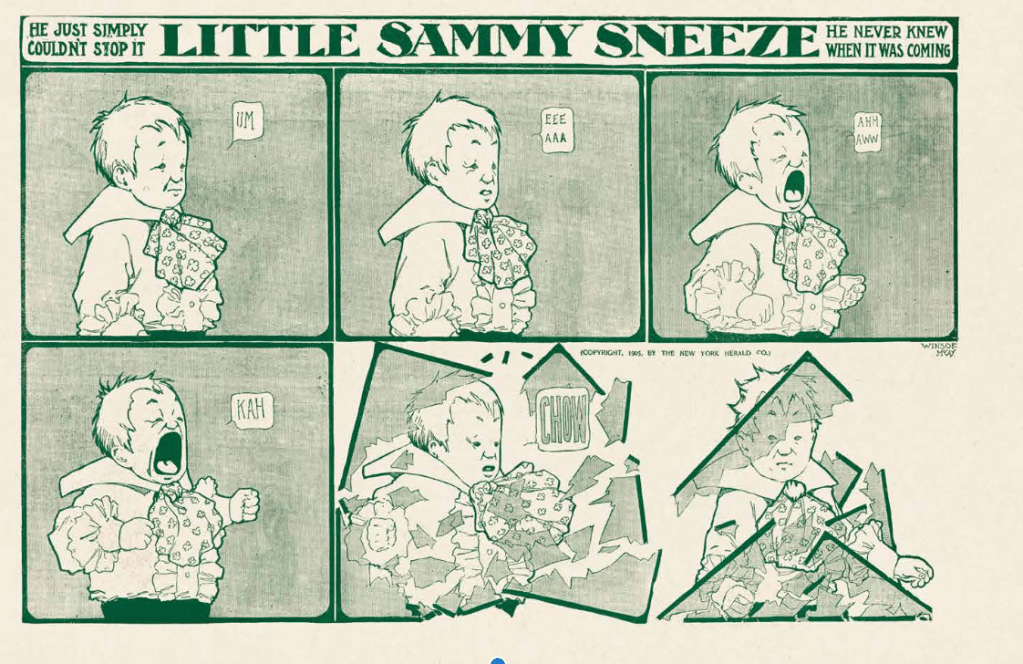

When the massive 21-inch by 17 inch, 152 page slab of early newspaper comic reprints bruised our laps in 2013, Sunday Press’s Society is Nix was a milestone. First of all, we had never seen so many examples from the innovative birthing years of the medium curated so intelligently, restored so beautifully and scaled to the original experience of the first Sunday supplements. Here we got that familiar crumbling mushroom forest in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, but now with the tonal nuance and size McCay intended. The Yellow Kid’s Hogan’s Alley was clear and detailed enough to appreciate all of that background business R.F. Outcault helped pioneer. We could best appreciate the sense of motion, and symmetry of Opper’s signature spinning figures in Happy Hooligan and Her Name Was Maude. And James Swinnerton’s often primitive-seeming linework revealed its expressiveness and intentionality when viewed closer up. Taking its title from a proclamation by the Inspector about the unruly Katzenjammers (“Mit dose kids, society iss nix!”), the book captured the creative freedom of a medium that hadn’t settled yet on a form, let alone a business model. Editor/Restorer Peter Maresca was unrivaled both in his eye for the right exemplary strip as well as his sheer skill in reviving the original color and detail from these yellowed, faded paper. For the last. Decade, Society is Nix remained indispensable for any fan or historian of the medium.

Fantagraphics has joined with Sunday Press to issue a Society is Nix revision of the original. Most notably it is scaled down to 13.2 inches by 16.8 but expanded to 168 pages with about 25 added comics. More modestly priced at $100, the book maintains excellent paper and printing quality. And even at this smaller scale, it remains immersive. The publisher has not given a detailed run down of what is new here, and because some of the layout has been reformatted and reordered it is hard to eyeball it myself. According to Fantagraphics, some examples of the same strip have been swapped in, and some of the fantasy-related strips have been taken out to be added to a planned revision of its Forgotten Fantasy compilation.

[UPDATE: Fantagraphics and Peter Maresca provided more detail about changes/additions to this revised edition. I am quoting it here: “The new edition of NIX has the same essays from the first edition. For a more comprehensive look at the era, we have added twelve pages and twenty-eight new comics. Included are early comics pages from eight artists not represented in the first edition, such as Louis Wain (famed cat illustrator), Carl Anderson (creator of Henry), and the New Yorker’s Rea Irvin (Eustace Tilley). In addition, the appendix with biographies of the 70 “Founders of The Funnies” is now fully indexed, referencing page numbers for each artist.”]

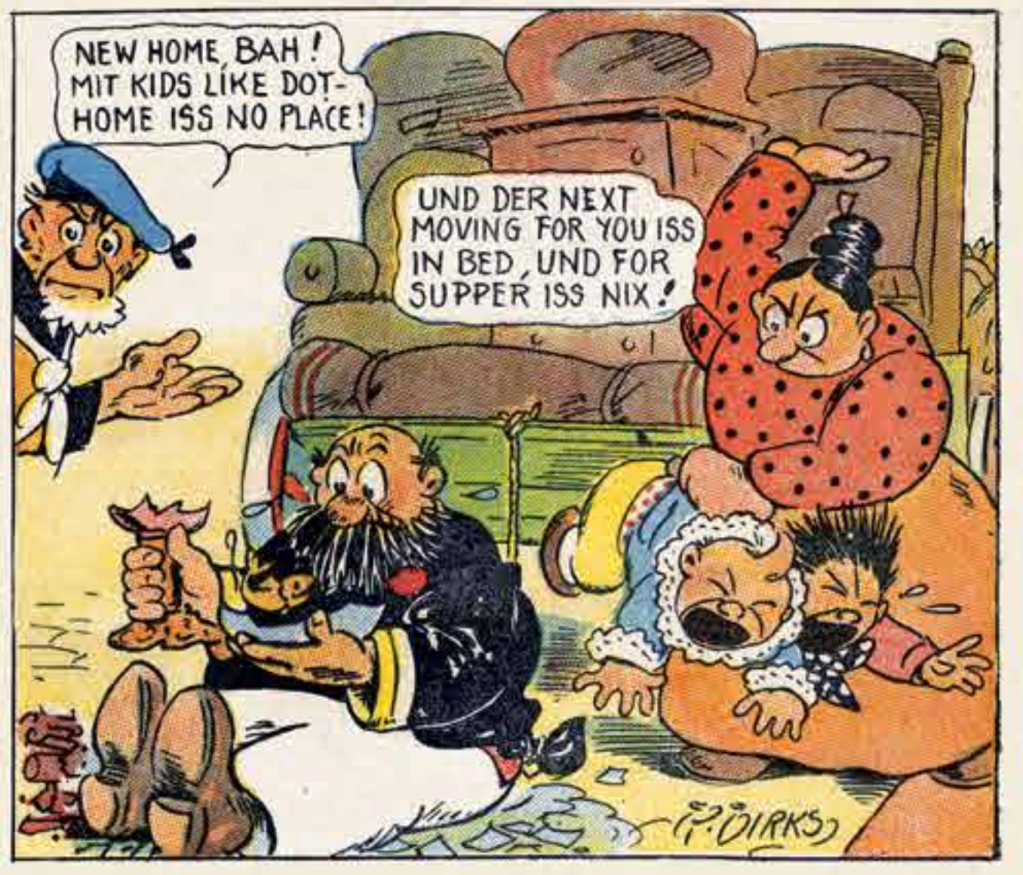

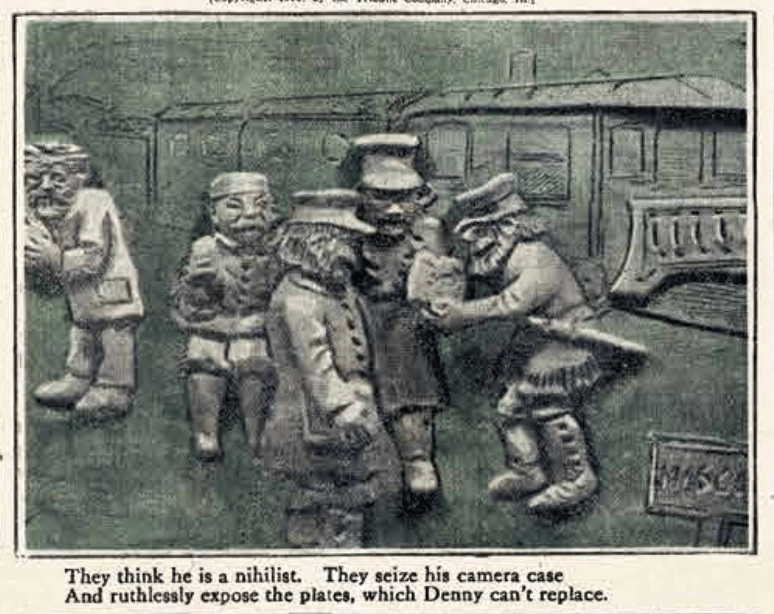

Society is Nix is more than the best view of the early Sunday supplements that we have. It is also a fine illustrated history of the first 15 years of the medium. Maresca frames this birthing period as “Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strip 1895-1915.” For him the “anarchy” was both in form and theme. Newspaper cartooning had no rules then, but it had the space to leverage sequencing, scale and color to play freely with things like panel structure, line drawing and figure styles. And so, Maresca brings us through chronologically a compilation of some of the best examples of that radical innovation. We see Walt McDougall finding layouts and perspectives that capture urban chaos. We see Rube Goldberg, Walter Bradford and George Herriman experiment with early screwball aesthetics. We get a good sampling of Rudolph Dirks evolving the Katzenjammers from pantomime pranks to wider adventures and schemes. And rarely reprinted innovators like Paul West, T.E. Powers, Jack Bryans and Hy Mayer get their due. They did things like turning panels borders into walls and ceilings to become objects in the action. Or dispensing with detail altogether to dramatize through silhouettes. Or just dividing the full page in new ways that played with the cadence of depicting elegant movement. They were thinking hard about what to do with these new playthings.

And they loved to jam. One of Maresca’s preoccupations appears to be the early mash-up, when artists like Opper, Dirks, McDougall, Outcault and others would collaborate on group pages involving different strips and styles. Personally, I am not as taken with this early era ritual, and could have done with fewer examples of the underwhelming results of such collaborations. Still, the artist jams speak to how quickly the characters and artists became cultural celebrities (and commodities) in just a few years, and how such mash-ups could become special events.

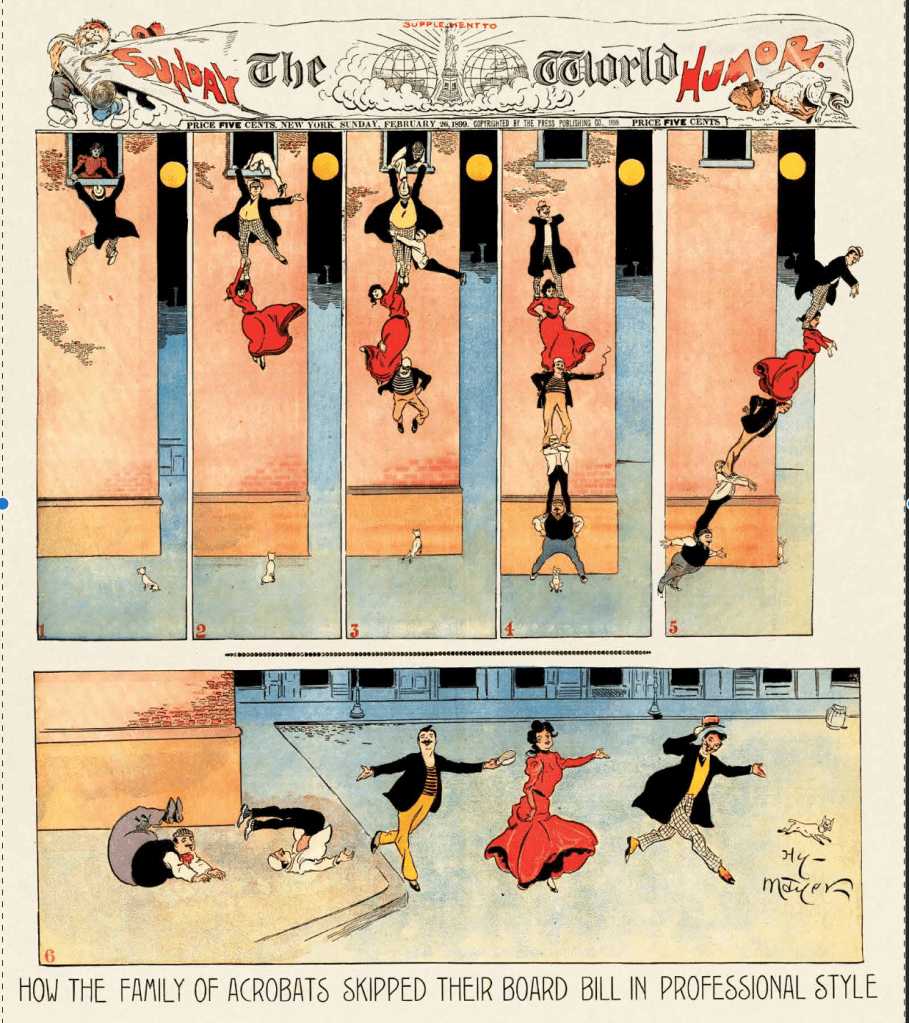

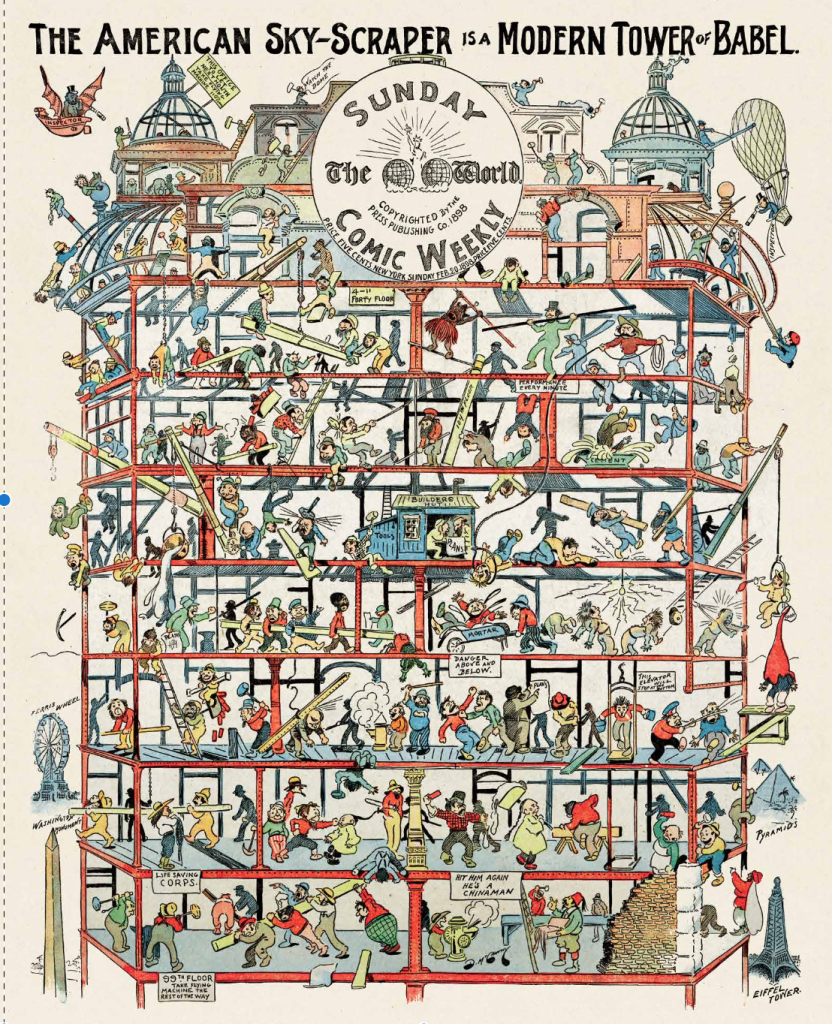

We also get to see eventual mainstays of the medium – Sydney Smith, Rea Irvin, Kate Carew, George McManus, Herriman – in their earliest development. Society is Nix is among the most thoughtfully curated collections I have seen. It combines a best of breed sampling of the greats with examples of formal pioneering and just some awesomely beautiful uses of the new tools at hand. Among my favorites is Hy Mayer’s 1899 “How the Family of Acrobats Skipped their Board Bill in Professional Style.” He uses panel layout, action flow and delicate lines to visualize a ballet-like grace on the page. Dan McCarthy’s 1898 “The American Skyscraper is a Modern Tower of Babel” fills the Sunday page with a cross-section of construction on a futuristic skyscraper. Every New York ethnic stereotype is employed taunting, pranking and bossing one another, but it us all framed as American progress. McCarthy’s image is one of the best examples of how the cultural themes and design innovations of early comic strips could merge. The ethnic stereotyping that informed many strips of the day represented much more than simply policing white supremacy. It was part of a rowdy and rude conversation about cultural identity, generational change and assimilation that was happening both across and within emigree groups.

As Maresca notes, the “anarchy” of which he speaks was not just aesthetic; it was thematic. The early newspaper artists, like their upstart publishers, were rejecting the gentility of the magazine humor and illustration in Puck, Judge, Life and embracing a diverse audience with rowdier downtown sensibilities. The violence, prankishness, sheer snark of these comics embodied an “anarchy borne of a broad antipathy to the status quo; hilarity borne of a disrespect for authority, be it one’s parents, employers, or the cop on the beat,” Maresca writes. And he is joined in the first 23 pages of indispensable front matter by leading comics historians to elaborate on the argument. Thierry Smolderen outlines the 18th and 19th Century roots of the form by tying the satire of British novelists to the spirit of Töpffer and his influence on American cartooning. Pieces by Richard Samuel West, the late R.C. Harvey, Alfredo Castelli, and Brian Walker outline the newspaper history and controversial critical response to the rudeness, violence and disrespect for authority evident to all in these early strips. David Gerstein gives an appreciation of the original comics anarchists, Hans and Fritz Katzenjammer. And Paul Tumey finds the roots of screwball sensibilities here as well. Maresca wisely includes several contemporaneous accounts that help in the larger project of this book, to make you feel immersed in the aesthetic and cultural feel of this seminal moment in comic strip history.

It adds up to a fine thumbnail history of the early newspaper years, which also serves to put this era into an important historical continuum. The Yellow Kid did not invent comics so much as mark a transition of a rich tradition of illustration, caricature and cartooning to a more industrialized phase. As the newspaper comics became not only the first mass medium of the new century but a massive business asset for publishers, “anarchy” seemed less marketable to increasing layers of editors and salesmen. Syndication into a cost-to-coast network of urban and rural papers becomes big business after 1910, and so capitalist hegemony sets in. Less offensive sitcom, adventure and screwball start to seem safer. The daily/Sunday panel grids lock into formats that never upset the market. I love in particular Brian Walker’s take on how a catalog of comic strip taboos evolved: no divorce, no direct racial/national/religious insults, no death and disease, and no women smoking. It is remarkable that the most buttoned-down, family-friendly and circumspect mass medium of the last century somehow managed so much action, satire, eroticism, naturalism, and violence within such handcuffs.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nice review! Any chance you could tell us what’s on the new pages?

Hannah – I tried to map the new edition with the old but gave up as the format and order changes made it too overwhelming. I would have to do a page by page index of both and compare. All the front matter is the same and my impression is that a lot of the new material are swapping in new examples of the same strip. The reformatting of the front matter and some of the comics have added pages as well. I have tried to get Fantagraphics to give me a clear list I could share but nothing yet. I wish I could do better but I dont have the patience to catalog and compare every page. My feeling is that owners of the old version aren’t missing much by not buying the new one.

Pingback: 2025 Comic Reprints: Rediscovering Lost Classics – Panels & Prose