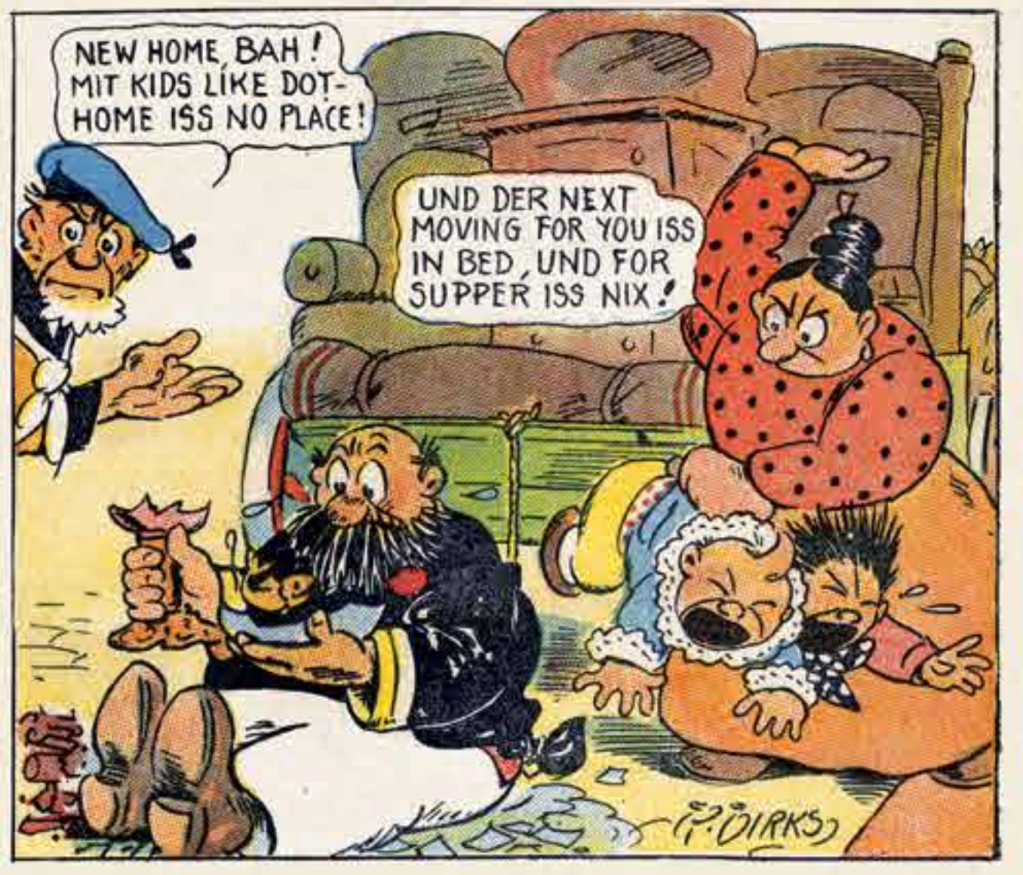

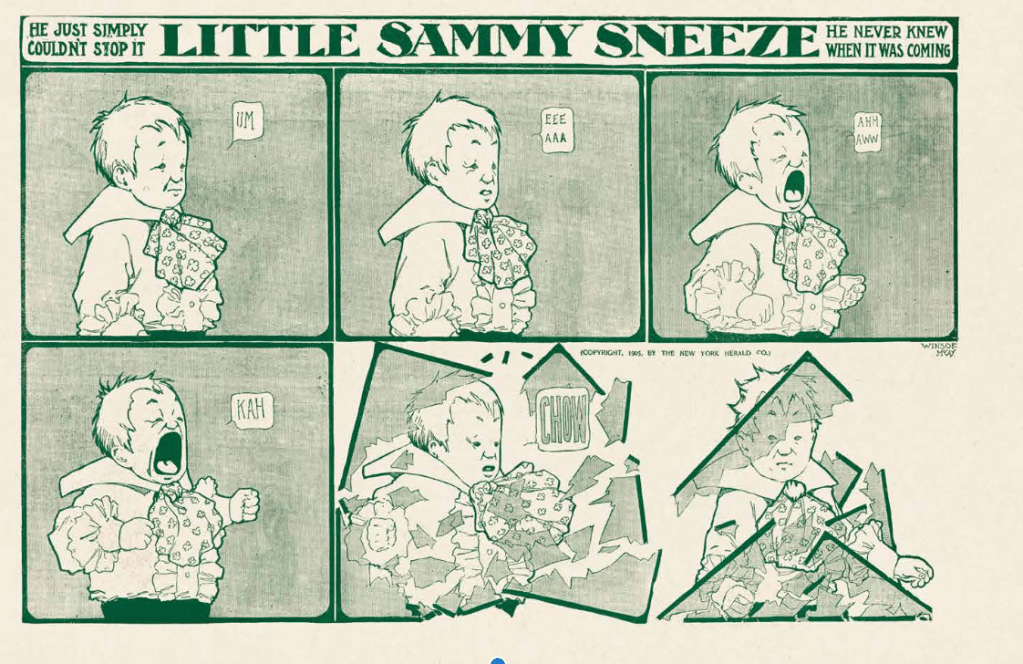

When the massive 21-inch by 17 inch, 152 page slab of early newspaper comic reprints bruised our laps in 2013, Sunday Press’s Society is Nix was a milestone. First of all, we had never seen so many examples from the innovative birthing years of the medium curated so intelligently, restored so beautifully and scaled to the original experience of the first Sunday supplements. Here we got that familiar crumbling mushroom forest in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, but now with the tonal nuance and size McCay intended. The Yellow Kid’s Hogan’s Alley was clear and detailed enough to appreciate all of that background business R.F. Outcault helped pioneer. We could best appreciate the sense of motion, and symmetry of Opper’s signature spinning figures in Happy Hooligan and Her Name Was Maude. And James Swinnerton’s often primitive-seeming linework revealed its expressiveness and intentionality when viewed closer up. Taking its title from a proclamation by the Inspector about the unruly Katzenjammers (“Mit dose kids, society iss nix!”), the book captured the creative freedom of a medium that hadn’t settled yet on a form, let alone a business model. Editor/Restorer Peter Maresca was unrivaled both in his eye for the right exemplary strip as well as his sheer skill in reviving the original color and detail from these yellowed, faded paper. For the last. Decade, Society is Nix remained indispensable for any fan or historian of the medium.

Continue readingMad Men Angst: Dedini, Shulman and Self-Hating Suburbia

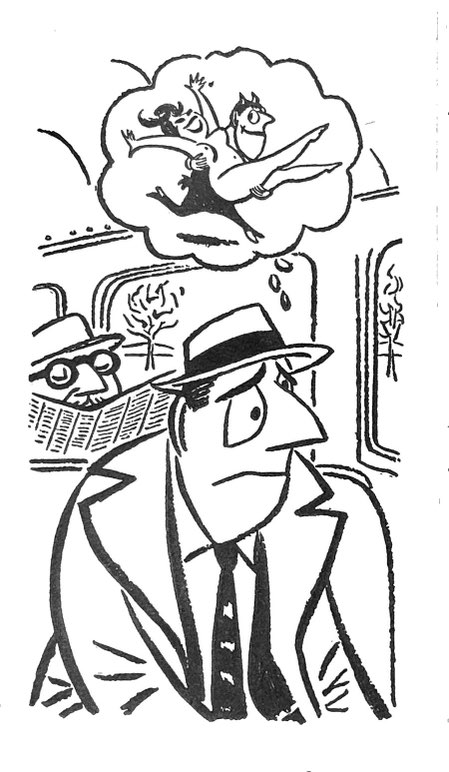

You may not think you know Max Shulman and Eldon Dedini, but you have seen their stuff. Shulman was a comic novelist of the 1940s and 50s whose most famous, enduring creation was The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, a short story collection that became an MGM musical in 1953 and a genuinely witty TV sitcom (1959-1963). But throughout those those decades, Shulman was a bestselling satirist of mid-Century suburbia. His 1943 breakout college satire Barefoot Boy With Cheek was followed by The Feather Merchants, the Dobie Gillis collection and Rally Round the Flag, Boys!. In their Bantam paperback releases, many of Shulman’s novels enjoyed cartoon complements by Eldon Dedini, best remembered as a longtime Playboy magazine regular. His cartoon style is immediately recognizable: highly abstracted balloon faces, sharp triangle noses, bright watercolor washes. His lascivious satyrs were among jhis signature series in Playboy.

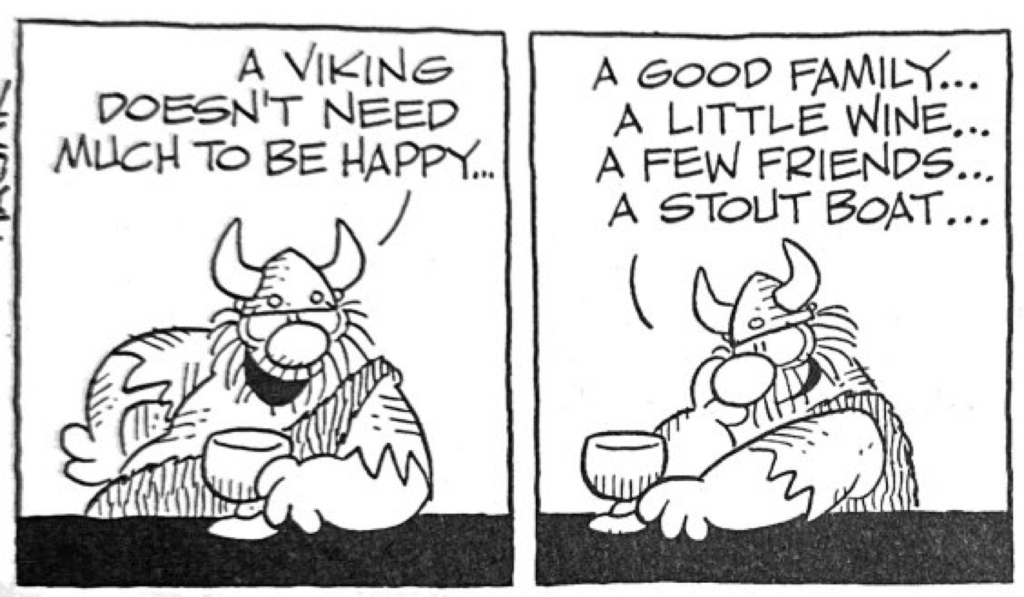

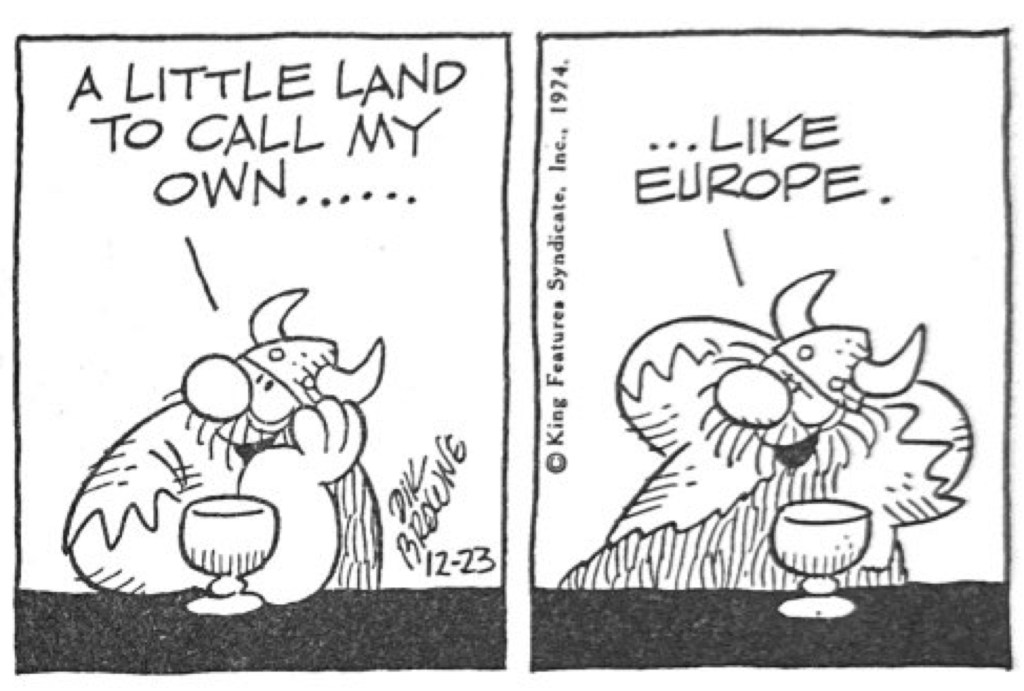

Continue readingThe Daily Anachronism: Fifty Years of Hagar

Like all of the most endearing comic strips. Dik Browne’s Hagar the Horrible came from a personal place. As Dik’s son Chris Browne tells it in the barbarian-sized collection, Hagar the Horrible: The First 50 Years (Titan, $49.99), the Brownes often joked about dad’s beefy, bearded, playfully irascible demeaner as Hagar-like. And it turns out, most of the eventual strip was loosely based on the character types and dynamics of the Browne household.

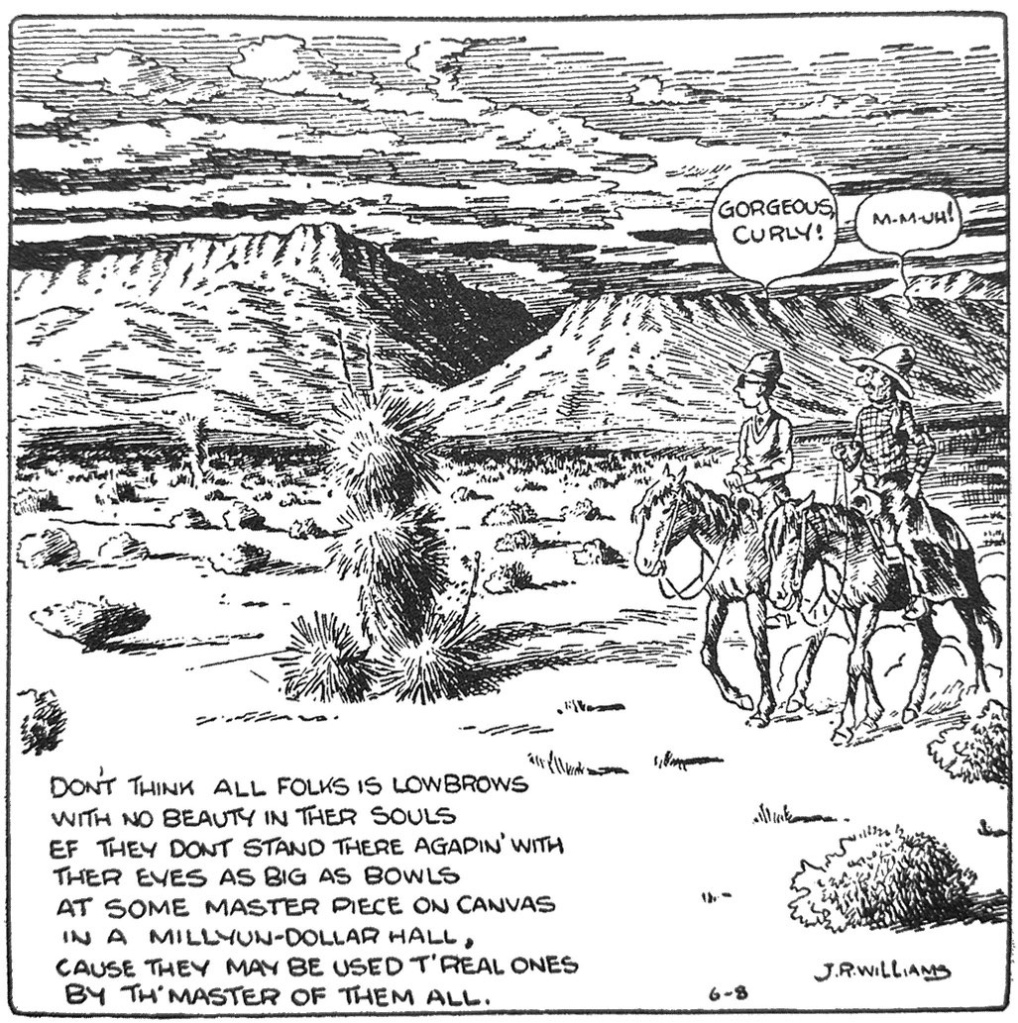

Continue readingCartooning the ‘American Scene’: Comics as Modern Landscape

We are such suckers for highbrow validation. Sure, we pop culture critics and comics historians talk a good game about bringing serious critical scrutiny to popular arts, our respect for the common culture…yadda, yadda. But our pants moisten whenever the intelligentsia deign to take our favorite arts seriously, or we find some occasional reference or connection between the “high” and “low” culture labels that we claim to disown. Comic strip histories love to gush over Cliff Sterrett’s appropriation of Cubist stylings in Polly and Her Pals. Although his dalliance with cartooning was brief, Lyonel Feininger’s Expressionist turn in the Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie loom so large in comics history you would think he was a beloved mainstay of the Sunday pages. In face, he was a fleeting presence. Picasso’s devotion to the Little Jimmy strip suggests somehow that Jimmy Swinnerton was onto something deeper than it seemed. And of course the critical embrace of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat started early, when Gilbert Seldes and e.e. Cummings, among others, primed us to believe the greatest of all comics for its surreal aesthetic and mythopoeic narrative.1 Never mind that the strip suffered limited distribution and perhaps narrower audience appeal. Indeed, an entire scholarly anthology, Comics and Modernism is a recent map of all the ways in which comics studies tries to wrap the “low” comic arts in the (to my mind) ill-fitting coat of high modernism.2

Continue reading

They Had Faces Then: Close-Ups, 50s Photo-Realism and the Psychological Turn

The turn to photo-realism in the adventure comics after WWII is well-documented and obvious in any review of the major strips. Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby, Warren Tufts’ Casey Ruggles and Lance, Leonard Starr’s On Stage, Stan Drake’s Heart of Juliet Jones, John Cullen Murphy’s Big Ben Bolt are just some of the clearest examples. The stylistic foundation had already been set in the 1930s, of course by Noel Sickles (Scorchy Smith), Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates) and Hal Foster (Prince Valiant). They moved adventure strips away from the more expressionist modes of Gould and Gray, or the cartoonish remnants of Roy Crane (Wash Tubbs and Capt. Easy) or the sketchy illustrator style of a Frank Godwin (Connie). .But it is really in the post-war period that we see a clear ramping up of fine line, visual detailing, naturalist figure modeling and movement, as well as full adoption of cinematic techniques.

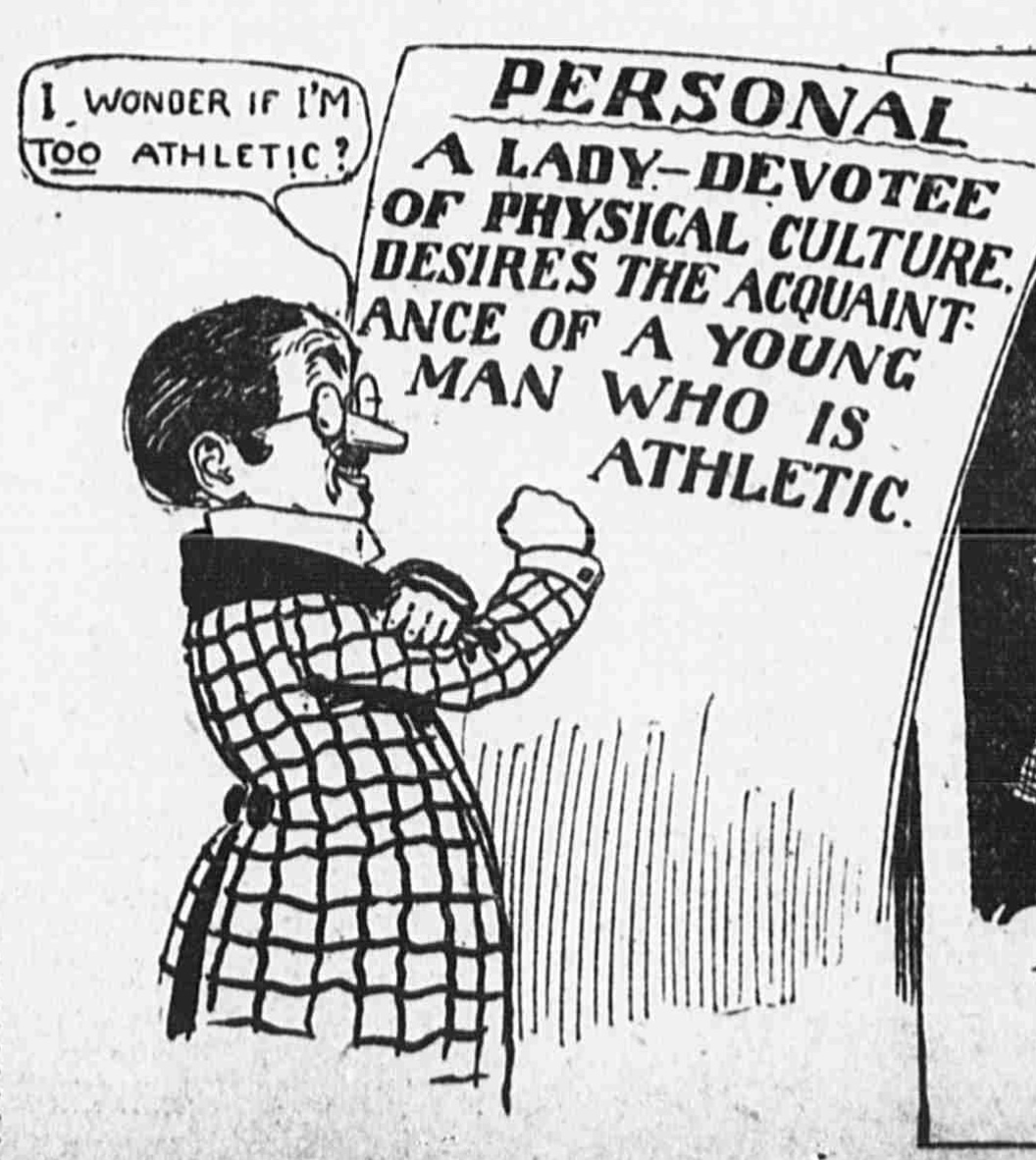

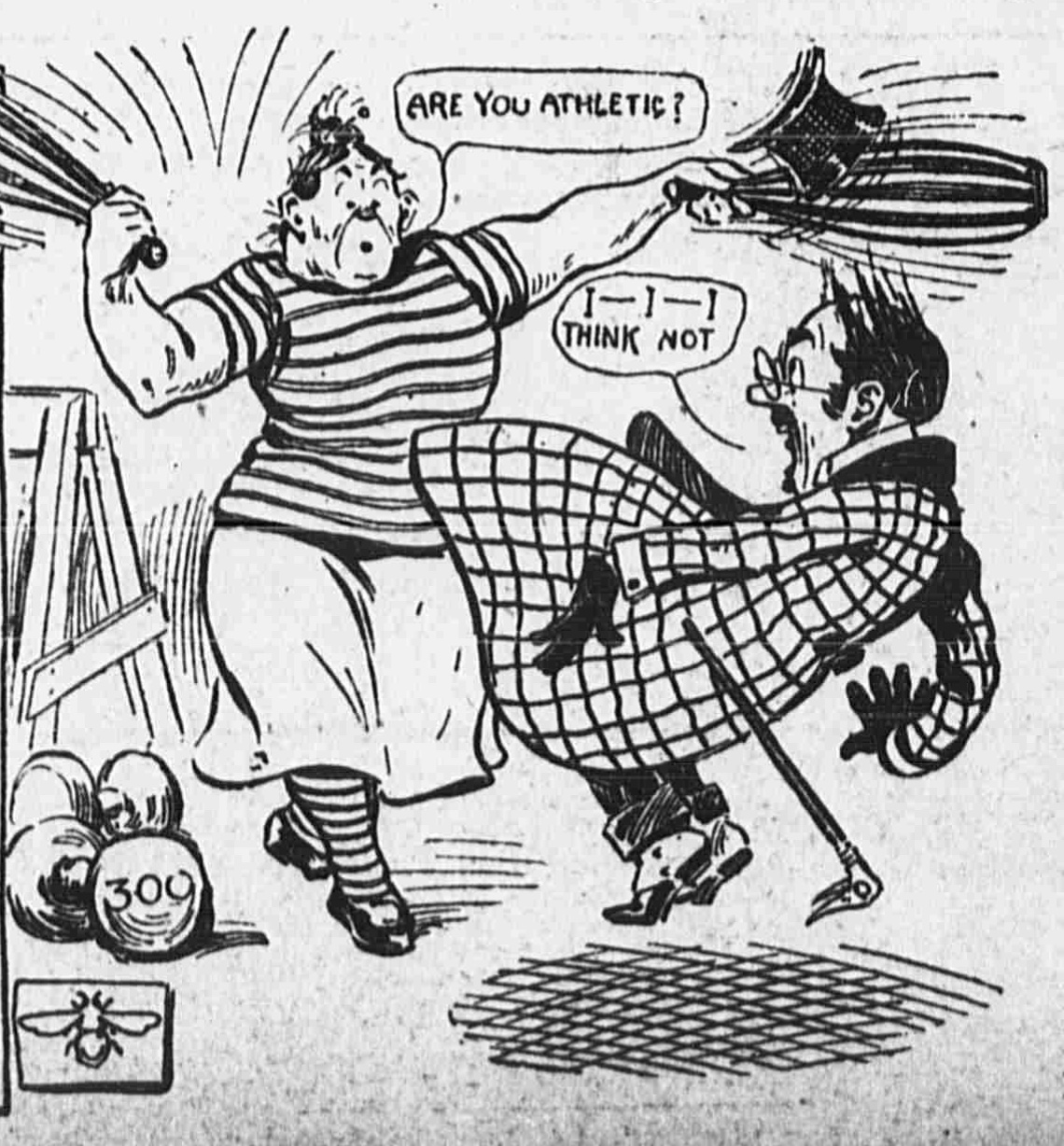

Continue readingSwipe-Right Follies, Circa 1904

Apparently, getting a date was never easy, and the contemporary swipe-left, swipe-right mobile media is just the latest twist on an old genre – the “personals.” This short-run comics series of 1904, “Romance of the ‘Personal” Column,” in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World reminds us that Americans were already jaded about the deceptiveness of these early versions of the dating app over a century ago. The strip followed a familiar formula. Our misbegotten suitor finds that the reality of his blind date is frighteningly different from his impression of the ad. Thus, he flees in panic; from a widow’s horde of kids, a muscle-bound athlete, and, in a racist turn that was standard in the day, a “dark brunette” who turns out to be Black. “Romance of the ‘Personal” Column” only ran a handful of times, but it is the kind of early comic strip trifle that surfaces a number of important themes in the cultural history of the first newspaper strips.

Continue readingGasoline Alley’s Emotional Realism

Frank King’s Gasoline Alley may be the “Great American Novel” of the 20th Century we didn’t know we had. This remarkable multi-generational saga of the Wallets evolved in several panels a day across decades, exploring the domestic and emotional lives of small town Americans during a century of intense change. And in its heyday during the post-WWI era, this strip was singular in its affectionate embrace of suburban family life at a time when post-war disenchantment overwhelmed the intellectual class, when glamour, sex and emotion dominated the film arts and magazines and glitz dominated Hollywood. When more famous social commentators like H.L. Mencken, Walter Lippman and Sinclair Lewis lampooned, decried and doubted the small town American intellect – the so-called “revolt from the village” – King celebrated what Mencken called the “booboisie.” Comics historians often characterize the post-1915 period of the medium as a kind of literal and figurative domestication. As newspaper syndication expanded into every burg, the mass media business of comics needed to shave the edges off of a once-raucous and urban-focused art form. Shifting the focus to family relations and suburbia, relying on more repartee than prankish violence, made the comic strip more acceptable to a mass audience.

Continue reading