Hugh Hefner was famously supportive of cartooning in the pages of Playbpy for decades, in part because he was a frustrated artist himself. Samples of his own attempts at single panel humor surface from time to time in biographies of the legendary publisher and the history of his landmark magazine. Less well-known is that in 1951 and prior to his meteoric Playboy fame he published a collection of his own comic work focused on the theme of his beloved Chicago., That Toddlin’ Town: A Rowdy Burlesque of Chicago Manners and Morals. This was very much an insiders’ cartoon revue, as Hef broke the volume into Chi-town’s famous districts and infamous institutions like The Loop. Michigan Avenue, Bug House Square, North Clark Street, The El, and the activities for which they were famous: strip bars, b-girls, the city’s multiple newspapers, soapbox orators.

Continue readingTag Archives: 1950s

Like a Comet: Frazetta Races In

On Jan. 28, 1952, Frank Frazetta’s breathtaking talent for dramatically charged action and erotic, muscular figure drawing finally made its way into newspapers with one of the most gorgeous, if short-lived, strips of the decade, Johnny Comet. The eponymous adventure was set in the racing world, a theme that should have tapped naturally into the car customization craze of the 50s. It was ceonceived and distributed by the McNaught Syndicate, ghost-written by Earl Baldwin, but co-credited to Frazetta and 1925 Indianapolis 500 winner Peter DePaolo who served more as an advisor and was attached to the project to lend an air of authenticity. Hobbled perhaps by uninspired scripting, Johnny Comet failed to catch on despite its standout visual poetry.

Continue readingDick Tracy Battles The JDs: Flattop Jr. and Joe Period

Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy was created in the 1930s as a response to the romanticization of gangsters and declining respect for law enforcement. And throughout its run under the notoriously conservative artist made no secret of his disdain for many modern trends. In the 1950s when mania around “juvenile delinquency” dominated popular culture, Gould added to his famous rogues gallery a few of these teen terrorists. Most notable for its outright weirdness (even for Gould) are the 1956 episodes spanning Joe Period and Flattop, Jr., the son of one of Tracy’s most famous nemeses of the prior decade.

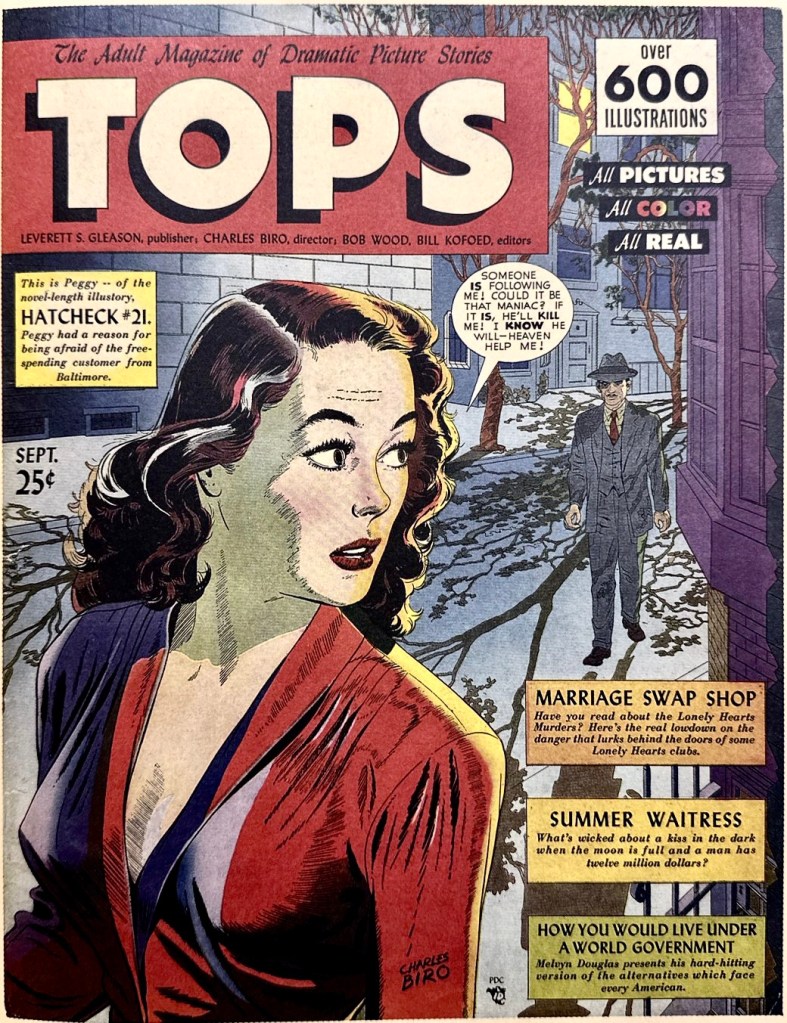

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: TOPS – When the Comics Tried Adulting

While this blog focuses mainly on the American comic strip in the first half of the last century, we have a soft spot here for comic books of the pre-code, pre-superhero era. For a brief shining moment after World War II, the comic book medium tried in vain to lurch into adulthood. Romance and crime genres especially aimed for older audiences. And the trend peaked with the horror, suspense and sci-fi comics of EC. The backlash was severe. Political hearings threatened government regulation, which the industry pre-empted with a self-censoring “Comics Code” that effectively consigned the American comic book to decades of the arrested adolescence of the superhero genre.

Continue readingDoc Hero: Rex Morgan, M.D. Is Here to Help

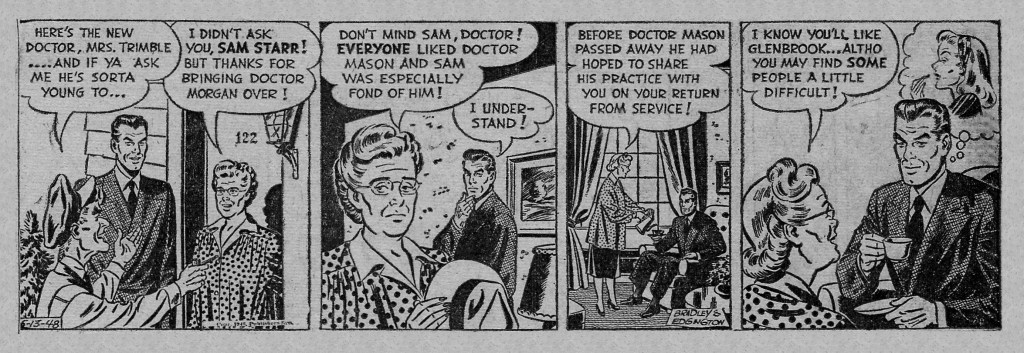

Remember when doctors were iconic pillars of respectability and authority in pop culture? Before alternative medicine? Before CDC missteps? Before drug company bribery? Before all expertise became “elitist conspiracy?” Remember Dr. Kildare? Ben Casey? Marcus Welby? And how about the most enduring of them all, Rex Morgan, M.D.? Launched on March 10, 1948, the doctor-driven soap opera was the brainchild of a psychiatrist, Nicholas P. Dallis, who wrote under the moniker Dal Curtis. His intent was to create a doctor hero who ministered not only to broken bodies but to overall mental and moral health. Young Dr. Morgan, apparently not long out of medical school, moves to the small town of Glenbrook to take over the practice of the burg’s departed, beloved practitioner. The strip was very much part of the psychological turn in American pop culture after WWII. Morgan represented that new generation of more enlightened experts of all things both scientific and emotional.

But at the same time, Rex Morgan M.S. rightfully remains a monument of 1950s iconography. For many years under the hands of main artist Marvin Bradley and backgrounder John Edgington, the strip had the bland realist style of contemporary advertising illustration. Characters showed minimal expressiveness; environments were just as pristine and inexpressive; houses, cars, furniture were just as generic; and any cartoonishness was saved for the offbeat minor players and comic relief.

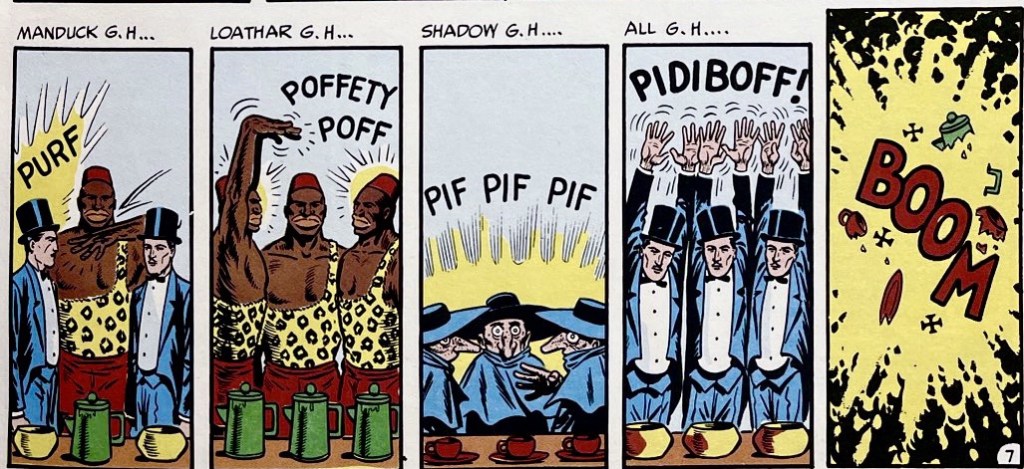

Continue readingKurtzman Turns The Funnies Into The Sillies

As part of his general send-up of modern popular culture in the original MAD magazine, Harvey Kurtzman took special care with his satirical takes on famous American comic strips. Most often aided by the uncanny mimicry skills of Will Elder, who seemed able to channel any cartoonist’s style, it was clear that their hearts were really in these stories. Whether it was Manduck the Magician, Little Orphan Melvin or Prince Violent, these parodies were coming out of deep familiarity of having been raised on these strips. And Kurtzman always zeroed in on the inane in pop culture as his target.

Putting Manduck into a mind-bending duel with fellow mystic The Shadow was an inspired but typical Kurtzman assault on the shallow and phoney in pop culture conventions.

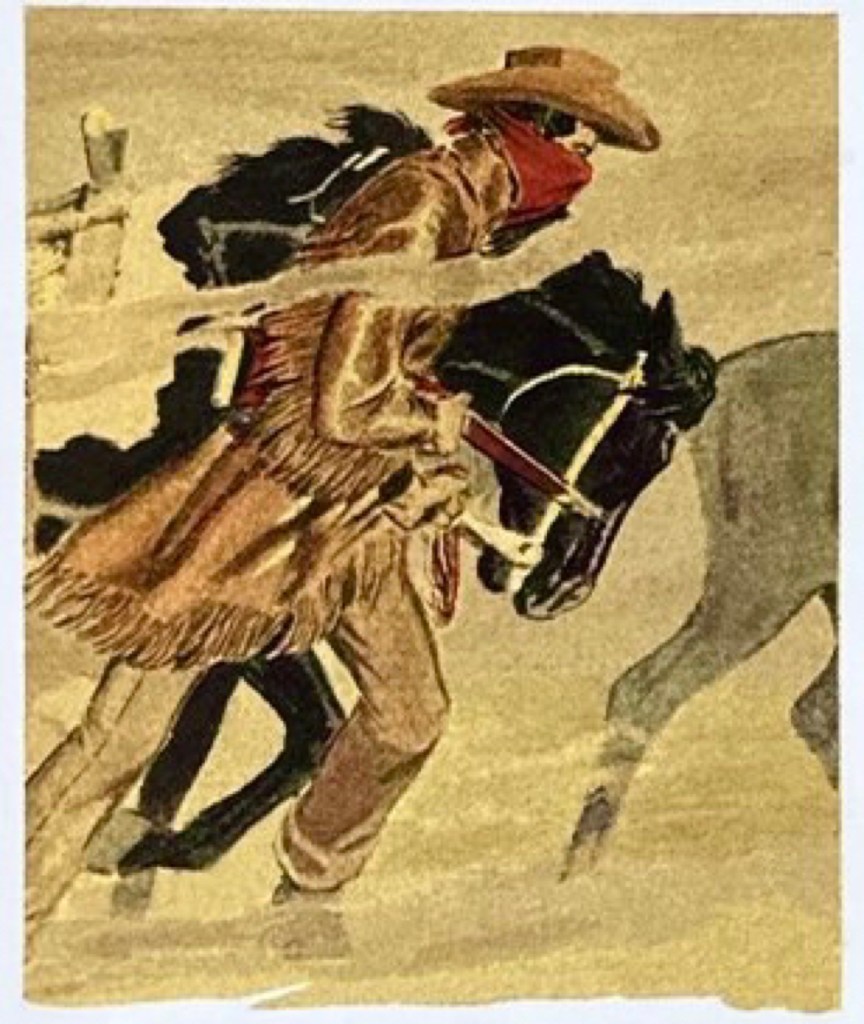

Lance: Warren Tufts’ Beautiful…Strange America

Lance (1955-60) was Warren Tufts’ masterful exploration of mid-19th Century American expansion, and it remains among the most breathtaking uses of the newspaper comics medium in its history. Tufts, who had previously fictionalized the Gold Rush in his wonderful Casey Ruggles (1949-55), was a self-taught savant of realistic illustration and frontier history. Lance embodies some of the signature qualities of the American newspaper strip. Visually, and much like Winsor McCay, Cliff Sterrett, Frank King, Hal Foster and Alex Raymond before him, and scouted new ways of using the full-page Sunday format and especially color to evoke emotions and a sense of place. And like Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, Percy Crosby’s Skippy and Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie, Tufts’ rendered a highly personal, idiosyncratic and often weird vision of America and humanity. Lance demonstrates how such individual and offbeat perspectives were still possible in the comic strip format, and could make this medium much different from other modern mass media that had become corporatized and collaborative.

Continue reading