“It is a old comical strip trick – pretendin’ th’ hero gotta git married.” It keeps “stupid readers excited,” Li’l Abner claims in 1952. Days later he unwittingly weds Daisy Mae, ending a nearly 20 year tease. But this time it was no “comical strip” trick. In fact, several perennial bachelors of the comics pages fell in a post-WWII rush to the altar. Along with Abner, Prince Valiant, Buz Sawyer, Dick Tracy and Kerry Drake all enjoyed funny page weddings between 1946 and 1957. Comic strip heroes were just following the lead of the real-world heroes returning from WWII. Desperate to make up for lost time and return to normality, over 16 million Americans got hitched in 1946, the year after war ended in Europe and the Pacific. But each of these strips framed the new normal in American life differently. As the best of popular art often does, Vale, Dick, Abner, Buz, Kerry and their mates offered Americans a range of stories, myths really, about what this new normal meant.

Continue readingTag Archives: adventure strips

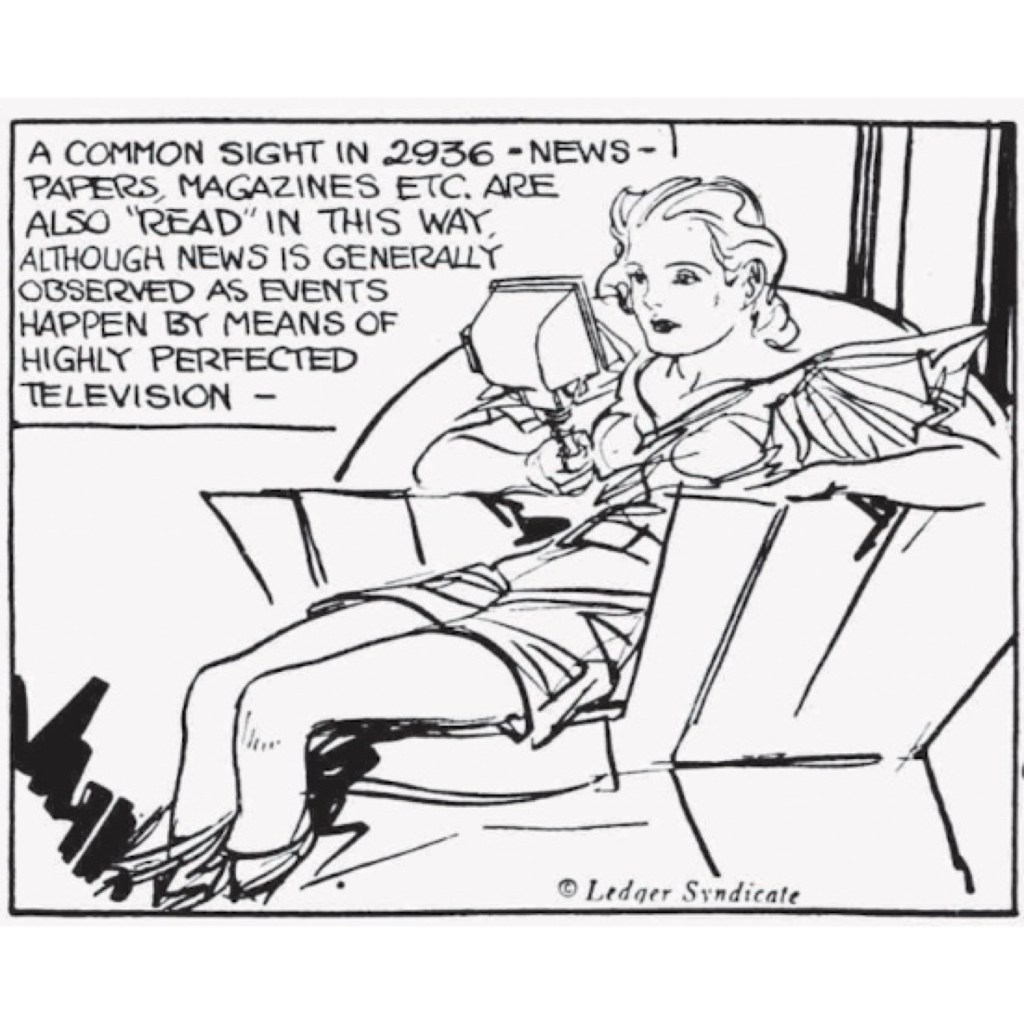

Your 2936 Model iPad…Via 1936

When Frank Godwin sent his adventure comic strip heroine Connie Kurridge a thousand yeas into the future, this amateur engineer had a field day imagining technologies of the next millennium. During the extended story arc, the Connie strip ran a “topper” on the bottom each week called Wonder Land. The content was often hosted by the “Dr. Chrono” character from the main storyline who had invented the time travel machine. the strip served as a kind of explainer series that elaborated on technical details related to that week’s tech of the future. But one week we get a particularly prescient future gadget that resembles the best steampunk visions from Buck Rogers.

Continue readingAmazon Dreams: Defending The Matriarchy in Depression Era Comics

“A hundred yard jump! And a girl soldier, too! Say, sister, need help?

The first thing Buck Rogers sees when he wakes from his 500 year slumber is a flying bare-legged woman…with a gun. That Jan. 7, 1929 strip launched American newspaper comics into a new age of heroic continuity strips, which historians have dubbed “The Adventurous Decade.”1 And across Buck, Flash (Gordon), Dick (Tracy), Pat (Ryan), the Prince (Valiant) and of course Tarzan, this decade in the newspaper back pages became famous for a pulpy hyper-masculinity that culminated in the rise of the superhero in the late 30s. And yet, as Buck’s premiere strip suggests, it would also be one of the weirdest stretches in the depiction of powerful women in popular culture. This would play out especially in adventure comics’ curious fixation with putting women in charge during the Depression years. Amazon tribes, criminal gal gangs, and futuristic matriarchies peppered adventure strips. We are all familiar with the creation of Wonder Woman in 1941 and her origin on the ladies-only Paradise Island.2 But this trope started in comics more than a decade earlier, first with Buck but then resurfacing in The Phantom, Tarzan, Alley Oop, and Frank Godwin’s Connie. Fantasizing about matriarchal societies within the adventure genre was not just a clever escapist plot device. Each of these Amazon worlds imagined different alternative societies where women called the shots and shaped the culture. Taken as a while, this pop culture trope suggested a deep ambivalence about the changing roles and independence of women. Putting women in charge was a kind of gender lab that played with ideas of feminine power under the stress of both Depression and modernization.

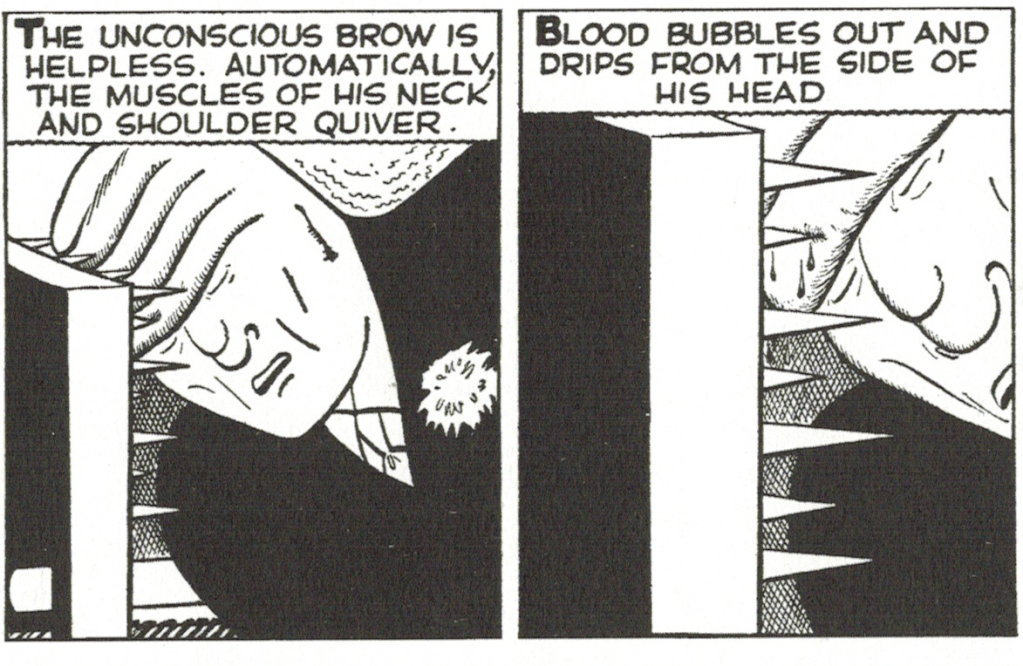

Great Moments: Dick Tracy and The Death of the Brow

The hallmark of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy is its surreal villains. Flattop, Pruneface, Mole, Mumbles, et. al. But Gould wasn’t satisfied expressing inner evil with outward disfigurement. He also loved to torture and kill them in equally grotesque ways during the prolonged hunt and chase sequences that were central to every Dick Tracy storyline. Gould wanted more than justice against evil. He wanted revenge and sometime literal pounds of flesh.

Continue reading“Tycoons of Comedy”: Building the Myth of the Modern Cartoonist

“But the [comic] strip has suffered from mass production and humor hardening into formula…. It has sacrificed its original spirit for spurious realism.” – “The Funny Papers”, Fortune Magazine, April, 1933.

Who could say such a thing in 1933, just as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers, Tarzan and Terry were about to launch what many consider a “golden age” of American comic strips? But in a major feature in its April 1933 number, Fortune magazine lamented the new adventure trend as a sign of the medium’s decline. In their telling, comics were losing an antic, satirical edge that had distinguished them from the gentility of American literature or saccharine romance of silent film. In particular, the Fortune piece (unattributed so far as I could tell), bemoaned the rise of the dramatic “continuity” strip in place of gags. They single out Tarzan in particular as a corporate product that suffers from too many scribes and artists not working together. “The strip wanders through continents and cannibals with incredible incoherence,” they say. And to be fair, who could have foreseen in 1933 that Flash, Dick, Terry and Prince Val were about to redirect the “funnies” from hapless hubbies and bigfoot aesthetics towards hyper-masculinized heroism and a new realism that readers found far from “spurious?”

Continue readingWhen Superman Was Woke?

America needed a hero. That is how Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster remembered the late-1930s world in which their modern myth soared. Everyone is familiar with the Clark Kent origin story: orphaned by cosmic circumstance; rocketed to Earth; fostered by the Kents in the american breadbasket; super-powered by our planet’s physics; and taking on his secret identity as the milquetoast reporter. It is that rare mass mediated pop culture fiction that genuinely approaches folk mythology. It is an origin that compels retelling for every generation. Less attention has been paid to his political roots, however. Every comic strip in the adventure genre especially has an identifiable political slant, most obviously in its choices of wrongs to right and the villains to subdue. The famously conservative Chester Gould in Dick Tracy and populist Harold Gray in Little Orphan Annie were the most overt. Less obvious was the implicit imperialism of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and most of the adventure pulps, which characterized non-Western cultures as at best quaintly primitive or at worst inherently brutal.

Continue readingFlesh, Fantasy, Fetish: 1930s and the Return of the Repressed

The sheer horniness of the otherwise circumspect American newspaper comics in the 1930s is as unmistakable as it is overlooked in the usual histories. I have written about the kinkiness of 30s adventure in bits and pieces in the past. But rereading Dale Arden’s “obedience training” at the hands of the dominatrix “Witch Queen” in Flash Gordon, reminded me how much unbridled fetishism romped through the adventure comics of Depression America. Any honest history of the American comic strip really needs to have “the sex talk” about itself.

Continue reading