Before Thanksgiving and the shopping season overcomes us, let’s make sure we start our annual Panels & Prose quick takes on recent books for comic strip fans. The pile of new releases is high and teetering, so let’s break this down into several posts this week and next. Today, we handle the celebratory and anniversary collections involving Peanuts, Hagar, Beetle Baley. For a hands-on look at these books, look for the video “Quick Flip” at the end.

Continue readingTag Archives: art

Review: Emanata and Lucaflects, Blurgits and Maladicta: Mort Walker’s Lexicon of Comicana

Like the comics art it dissects, Mort Walker’s legendary Lexicon of Comicana is unseriously serious. It is a lighthearted, profusely illustrated breakdown of the visual language of comics, the tropes, conventions, conceits, cliches that artists use to communicate a range of emotions and personalities at a glance. NYRB Comics has reissued this hard-to-find 1980 classic with a ton of supporting material from Chris Ware and Brian Walker. It is a must-have for anyone interested in the medium.

Continue reading

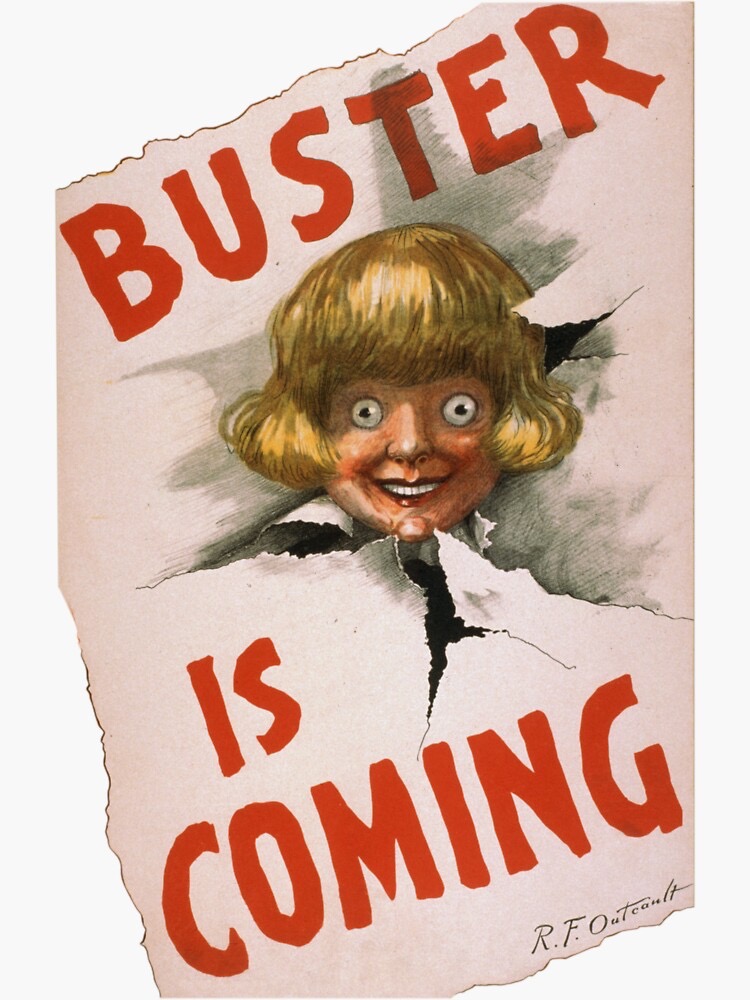

The Great Buster Brown ‘Scheme’ of 1906: Inventing Celebrity Endorsement

A 43-year-old man, something over 3 feet tall, is dressed in the signature, foppish, Buster Brown garb and wig. He commands his trained dog Tige to do tricks and then engages an audience of schoolchildren, sometimes hundreds, and prompts their pledge only to wear Buster Brown shoes. It was a good pitch in 1906. For local shoe merchants who secured this road show from the Brown shoe Company, “the scheme is the best they ever tried,” reported the trade publication Profitable Advertiser. This was the dawn of mass media celebrity endorsements and syndicated point-of-sale marketing programs.

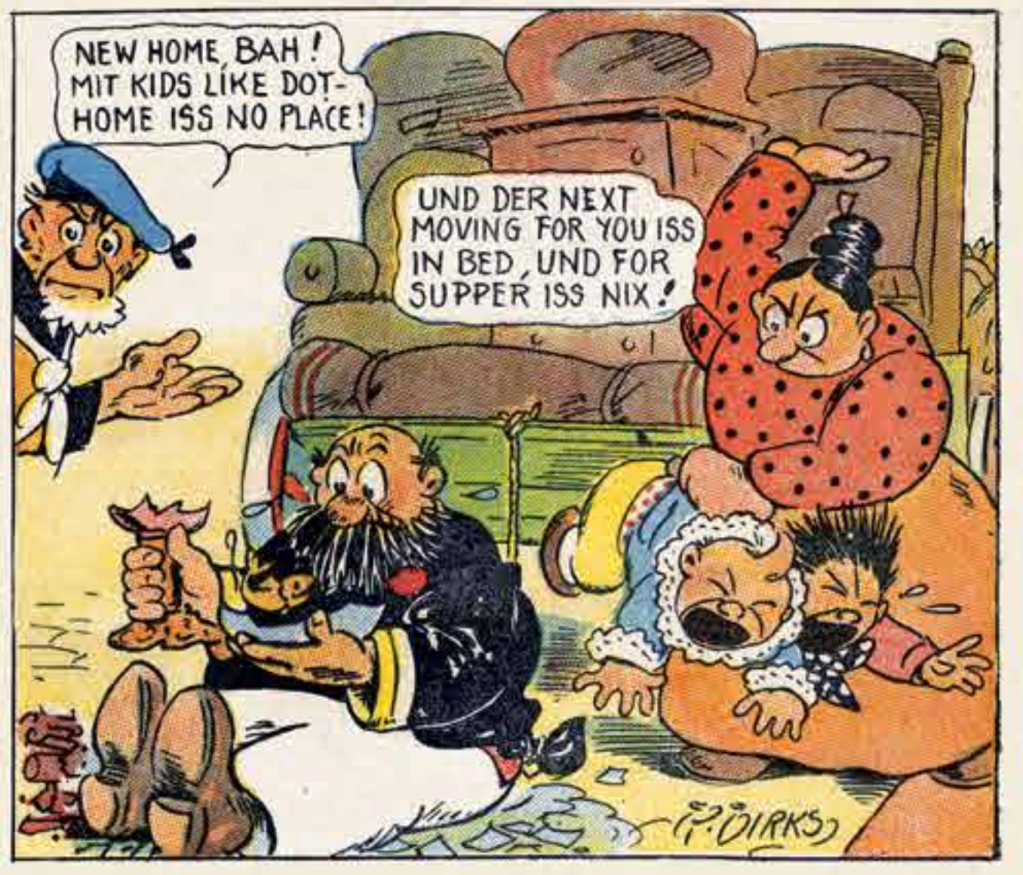

By the time creator R.F. Outcault started licensing his spectacular Buster Brown comic strip character in 1904, its boyish pranks and domestic chaos were familiar to audiences across the nation. Soon after premiering on May 4, 1902 in The New York Herald, the strip became a national sensation. At first blush, Buster seems an unlikely brand ambassador. Along with the Katzenjammer Kids and the many other copy cat pranksters of the “Sunday Supplements,” he was a quintessential comics “smart boy,” just more obviously middle class. His were the kind of antics that were commonly denounced by social reformers, clergy and teachers’ associations for their cruel pranks and disrespect for authority. And yet, here he was, his weekly sins somehow whitewashed by commodification. When Outcault sold licensing rights to the Brown Shoe Company in 1904, and launched the partnership at the St. Louis World’s Fair that year, he was also contracting Buster out to another 200 brands.

But it was the Brown Shoe Company that elevated the Buster Brown partnership into one of the longest-running comic character associations in history. And this was among the first examples of an emerging mass media ecosystem driving a new consumer culture of mass consumption. Brown not only married a celebrity to a mass produced and distributed product, but it showed how to standardize and syndicate a marketing program to a new nationwide market. Along the way, the Buster Brown marketing program pioneered marketing directly to kids in order to influence their parents’ buying habits.

Dubbed “Reception Tours,” the model provided for a Buster actor and a Tighe for day-long visitation to the retail outlet to drum up attention and drive shoe sales for the shoes. According to the St. Louis government’s history site, the Brown company hired up to 20 “midget” actors and trained dogs to staff the many road shows, which ran until 1930. But a forgotten article, “Buster Brown, Advertiser” in the obscure trade paper Profitable Advertiser gives us a more detailed look at “how the scheme is worked.” Retailers who agreed to buy at least 50 dozen pairs of Buster Brown shoes could access the program from Brown. The company provided a package that included the talent as well as marketing templates for local newspaper ads and handbills which the retailer agreed to buy in support of the Reception.

In this 1906 iteration, the company hired a 3-foot tall, 43-year old former salesman and “orator of ability,” Major Ray. In a trip to the town of Berwick, Buster and Tighe enjoyed a full day touring the local sites and manufacturing plants, visiting local officials and leading a parade through town. These tours became wildly popular local events. A Brown salesman claimed that “There were in the neighborhood of 8,000 to 10,000 people out to witness the reception.”

But Buster and Tighe kept their aim at the sales job. As Profitable Advertiser describes it, organizers scheduled the parade to pass local schools around dismissal time. Kids would gather back at the shoe store (or even rented theaters) to watch Tighe perform tricks and Buster entertain and pitch the crowd. They stood before a 30-foot banner across the store window declaring “Buy Buster Brown Shoes for boys and girls here. Every pair the best.” At times the crowd of youngsters were asked to raise their hands to acknowledge they will wear only Buster Brown shoes.

The Brown Shoe Company was writing the early scripts around modern media celebrity endorsement. Arguably, the American comic strip represented the first truly mass medium of the new century. Via newspaper networks and early syndication, premiere strips like Happy Hooligan, Katzenjammer Kids, Foxy Grandpa and Buster Brown were read on the same day coast to coast, a simultaneous, communal experience. That common content drafted nicely onto the new processes of mass production and distribution in manufacturing. Commodities now needed national identities. Consumer product branding emerged at precisely the time national entertainment heroes emerged in comic strips and soon in movies. The marriage of branding and celebrity seems natural and inevitable in part because they both came from a common source, the nationalization and standardization of both media and consumer goods. Consumer culture was being born, and in Buster Brown Shoes we see one of its weirder contours. Characters could be made into anodyne brands, while inert commodities could be given the gloss of personality.

“Tycoons of Comedy”: Building the Myth of the Modern Cartoonist

“But the [comic] strip has suffered from mass production and humor hardening into formula…. It has sacrificed its original spirit for spurious realism.” – “The Funny Papers”, Fortune Magazine, April, 1933.

Who could say such a thing in 1933, just as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers, Tarzan and Terry were about to launch what many consider a “golden age” of American comic strips? But in a major feature in its April 1933 number, Fortune magazine lamented the new adventure trend as a sign of the medium’s decline. In their telling, comics were losing an antic, satirical edge that had distinguished them from the gentility of American literature or saccharine romance of silent film. In particular, the Fortune piece (unattributed so far as I could tell), bemoaned the rise of the dramatic “continuity” strip in place of gags. They single out Tarzan in particular as a corporate product that suffers from too many scribes and artists not working together. “The strip wanders through continents and cannibals with incredible incoherence,” they say. And to be fair, who could have foreseen in 1933 that Flash, Dick, Terry and Prince Val were about to redirect the “funnies” from hapless hubbies and bigfoot aesthetics towards hyper-masculinized heroism and a new realism that readers found far from “spurious?”

Continue readingReview: A Few Words on Anarchy: “Society Is Nix” Gets Shrunken Yet Enlarged (Updated)

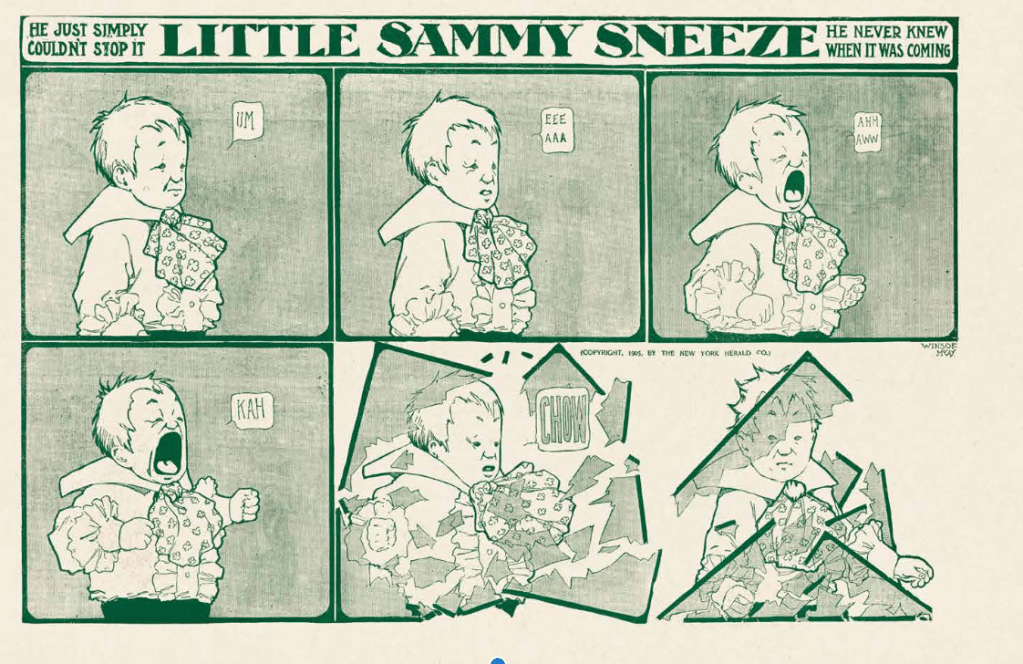

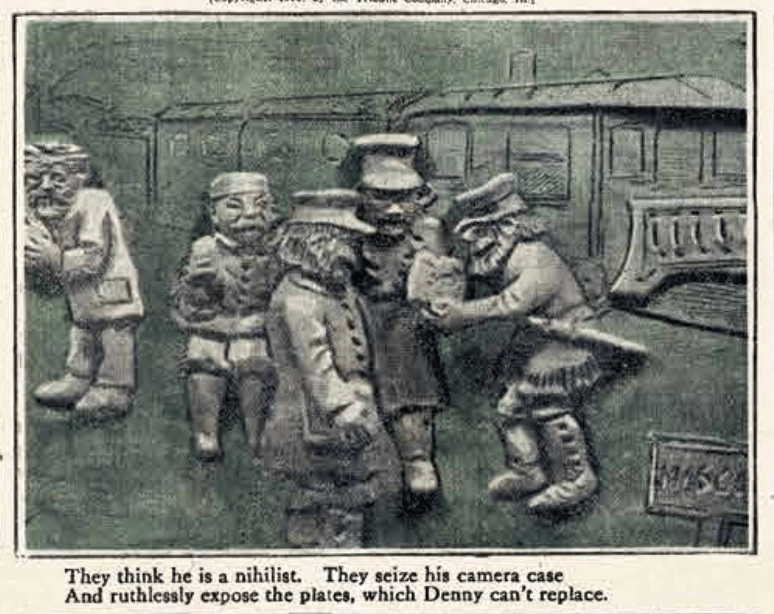

When the massive 21-inch by 17 inch, 152 page slab of early newspaper comic reprints bruised our laps in 2013, Sunday Press’s Society is Nix was a milestone. First of all, we had never seen so many examples from the innovative birthing years of the medium curated so intelligently, restored so beautifully and scaled to the original experience of the first Sunday supplements. Here we got that familiar crumbling mushroom forest in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, but now with the tonal nuance and size McCay intended. The Yellow Kid’s Hogan’s Alley was clear and detailed enough to appreciate all of that background business R.F. Outcault helped pioneer. We could best appreciate the sense of motion, and symmetry of Opper’s signature spinning figures in Happy Hooligan and Her Name Was Maude. And James Swinnerton’s often primitive-seeming linework revealed its expressiveness and intentionality when viewed closer up. Taking its title from a proclamation by the Inspector about the unruly Katzenjammers (“Mit dose kids, society iss nix!”), the book captured the creative freedom of a medium that hadn’t settled yet on a form, let alone a business model. Editor/Restorer Peter Maresca was unrivaled both in his eye for the right exemplary strip as well as his sheer skill in reviving the original color and detail from these yellowed, faded paper. For the last. Decade, Society is Nix remained indispensable for any fan or historian of the medium.

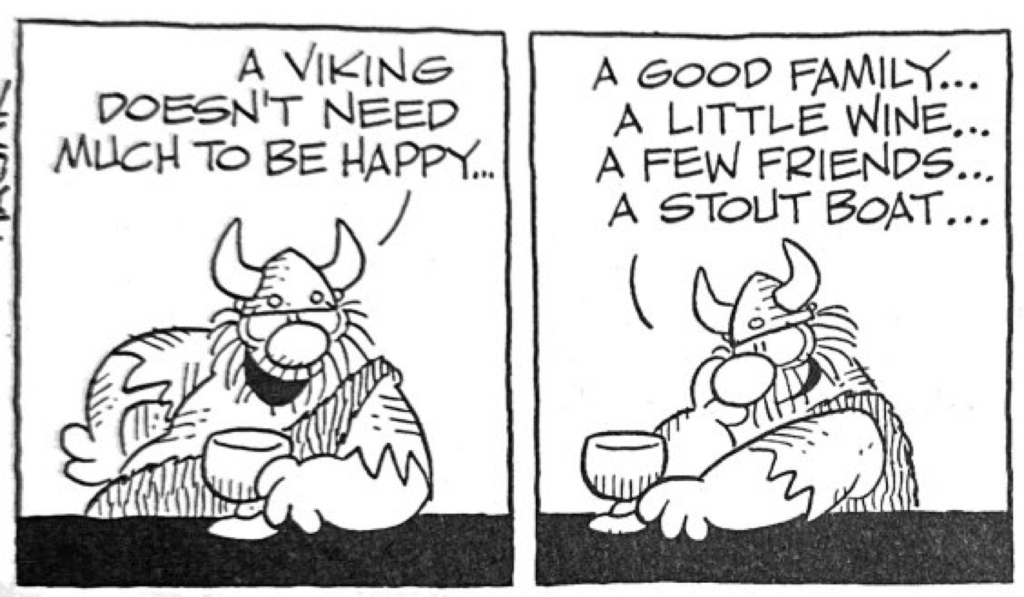

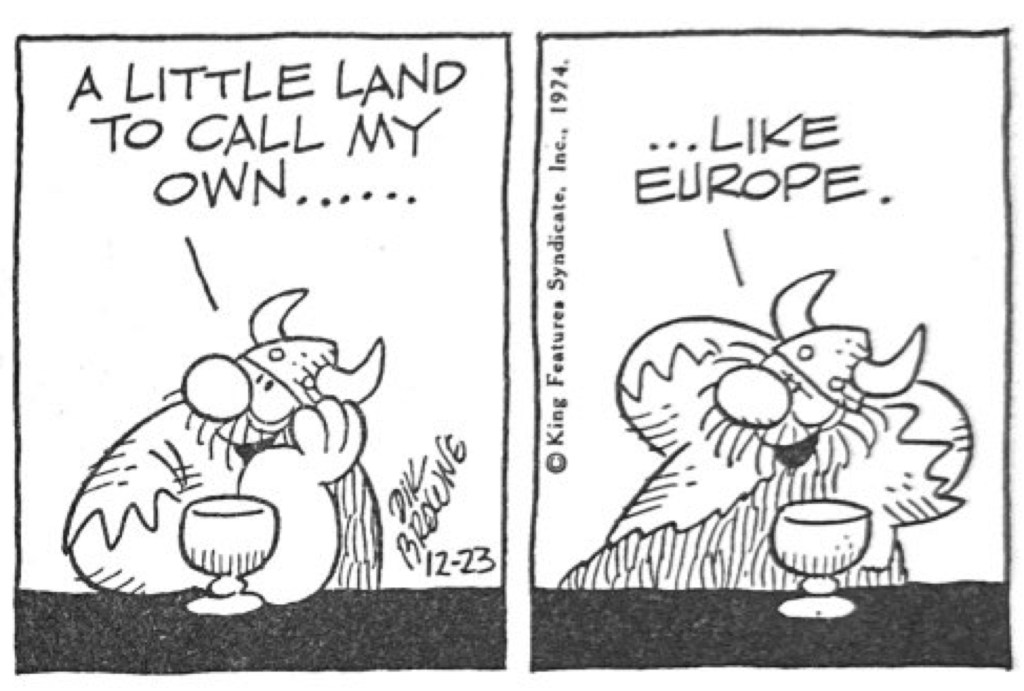

Continue readingThe Daily Anachronism: Fifty Years of Hagar

Like all of the most endearing comic strips. Dik Browne’s Hagar the Horrible came from a personal place. As Dik’s son Chris Browne tells it in the barbarian-sized collection, Hagar the Horrible: The First 50 Years (Titan, $49.99), the Brownes often joked about dad’s beefy, bearded, playfully irascible demeaner as Hagar-like. And it turns out, most of the eventual strip was loosely based on the character types and dynamics of the Browne household.

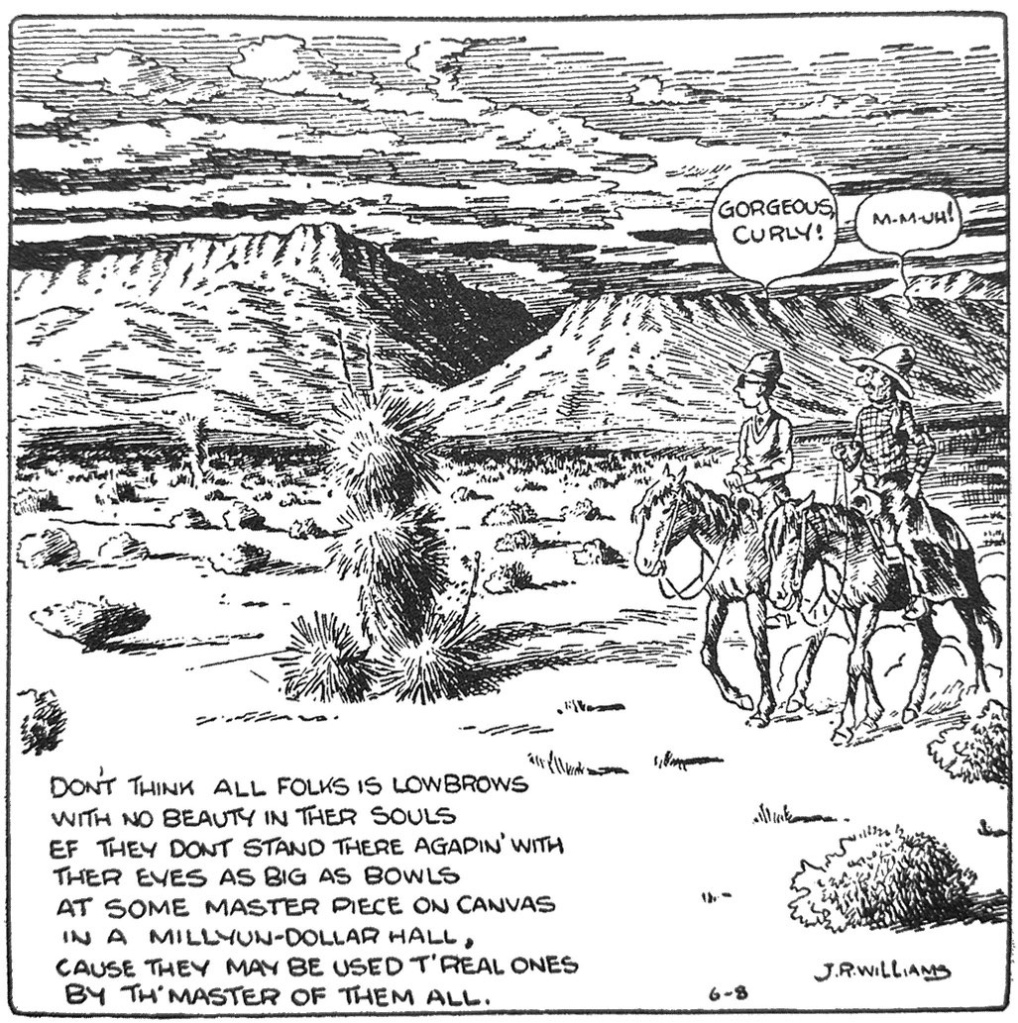

Continue readingCartooning the ‘American Scene’: Comics as Modern Landscape

We are such suckers for highbrow validation. Sure, we pop culture critics and comics historians talk a good game about bringing serious critical scrutiny to popular arts, our respect for the common culture…yadda, yadda. But our pants moisten whenever the intelligentsia deign to take our favorite arts seriously, or we find some occasional reference or connection between the “high” and “low” culture labels that we claim to disown. Comic strip histories love to gush over Cliff Sterrett’s appropriation of Cubist stylings in Polly and Her Pals. Although his dalliance with cartooning was brief, Lyonel Feininger’s Expressionist turn in the Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie loom so large in comics history you would think he was a beloved mainstay of the Sunday pages. In face, he was a fleeting presence. Picasso’s devotion to the Little Jimmy strip suggests somehow that Jimmy Swinnerton was onto something deeper than it seemed. And of course the critical embrace of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat started early, when Gilbert Seldes and e.e. Cummings, among others, primed us to believe the greatest of all comics for its surreal aesthetic and mythopoeic narrative.1 Never mind that the strip suffered limited distribution and perhaps narrower audience appeal. Indeed, an entire scholarly anthology, Comics and Modernism is a recent map of all the ways in which comics studies tries to wrap the “low” comic arts in the (to my mind) ill-fitting coat of high modernism.2

Continue reading