Trina Robbins is an under appreciated national treasure, alas, for some of the same reasons the cartoonists she presents here have been overlooked by too many comics histories. For the most part, cartooning was a man’s game in the 20th Century, and so has been the writing of its history. Except for Trina. Robbins was among the only female artists in an underground comics movement famous for its misogynist art. Her Pretty in Ink history of women in the field remains the major work, because she has waged a lonely battle for including this talented minority of comic artists.

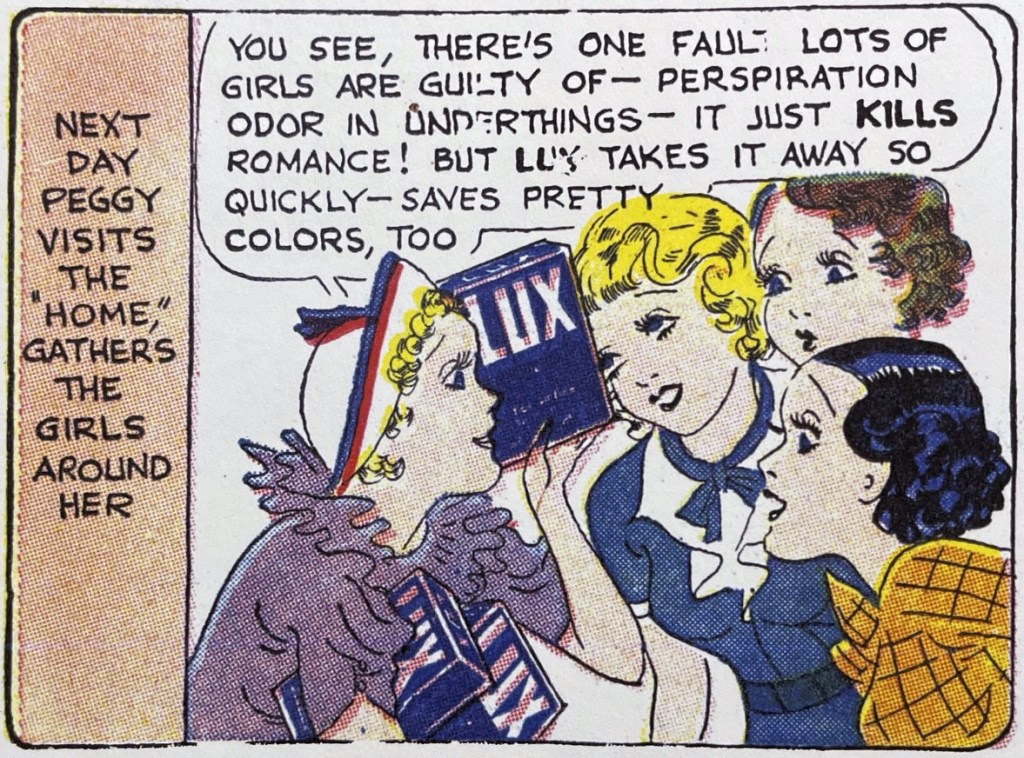

But Pretty in Ink had to cover so much ground, we didn’t get to dwell deeply into any artist or group. With The Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists in the Jazz Age, however, she gets the chance to reprint satisfying helpings of Nell Brinkley (fully 50 pages!), Eleanor Schorer, Edith Stevens, Ethel Hays, Fay King and Virginia Huget. Since this is more a history in reprints than a history with reprints, Robbins shows more than tells. But she shows so much about how these women helped define the post-WWI era, or at least mass media’s aspirational version of it. Their focus on social interactions and fashion come through as expressions of feminine power and personality.

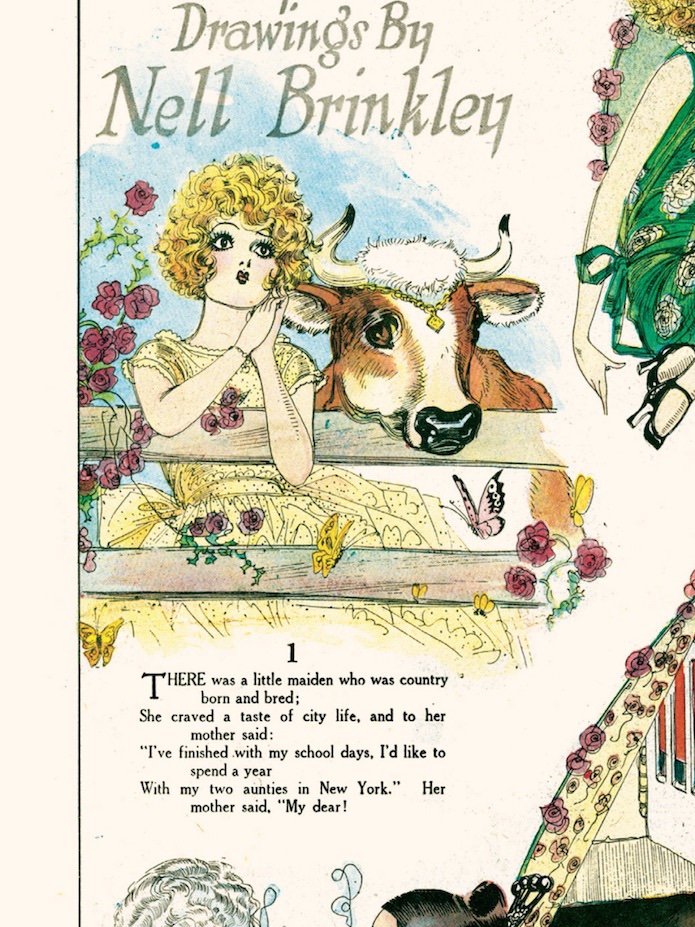

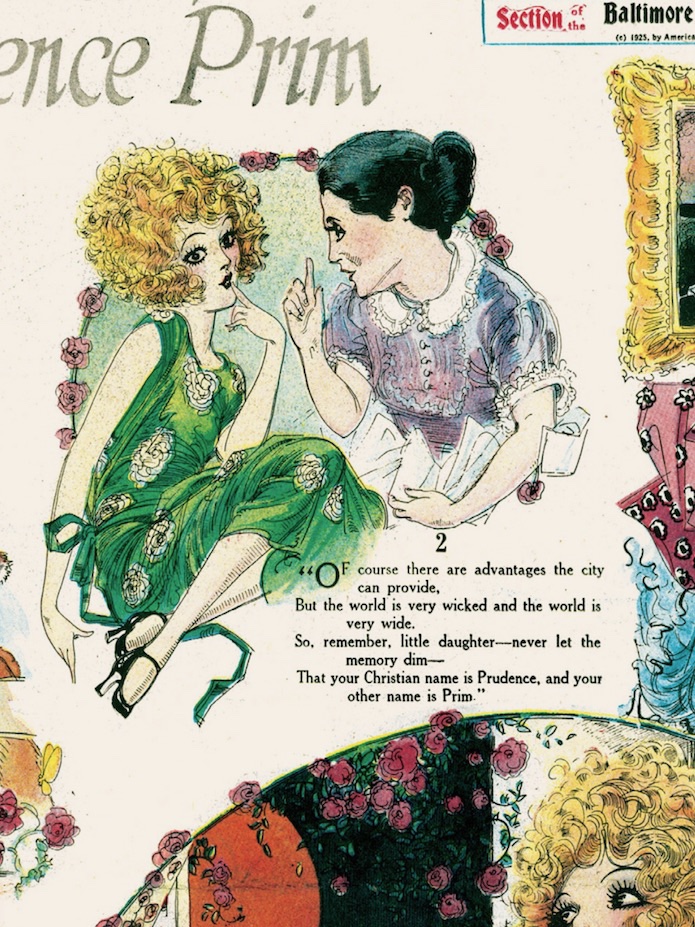

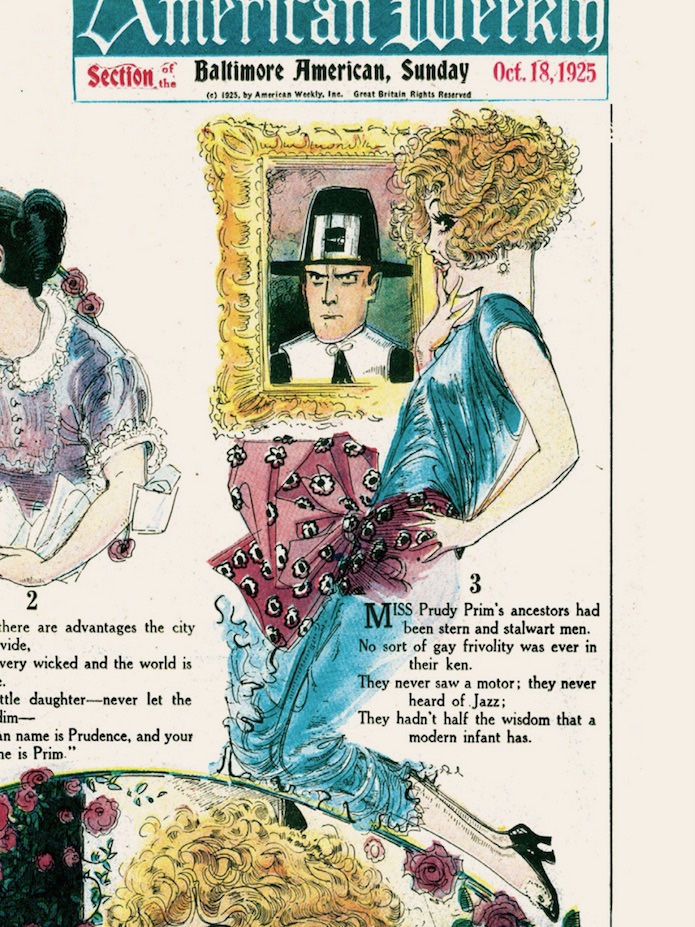

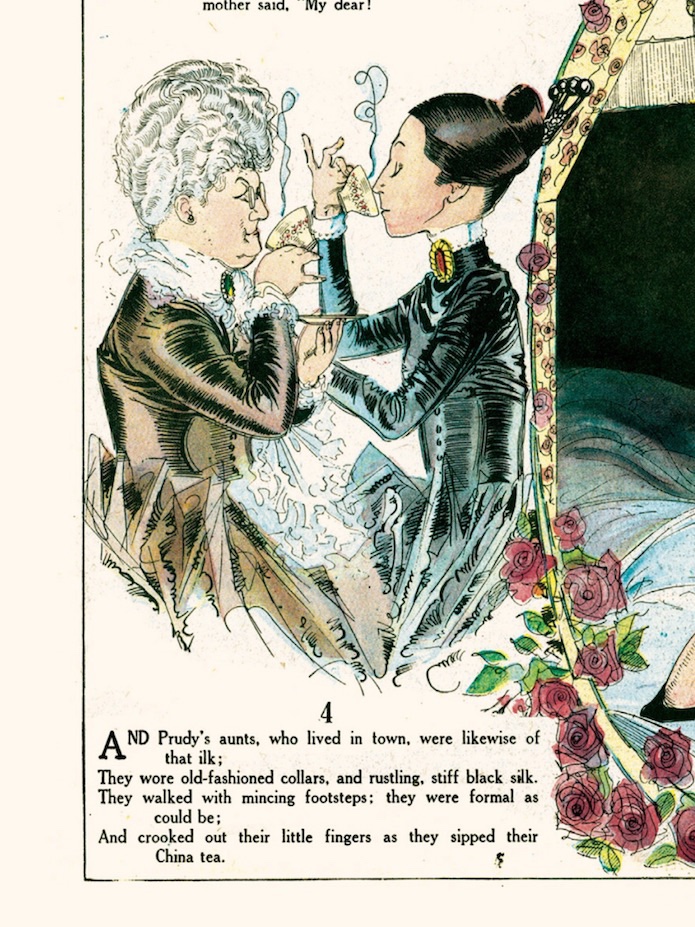

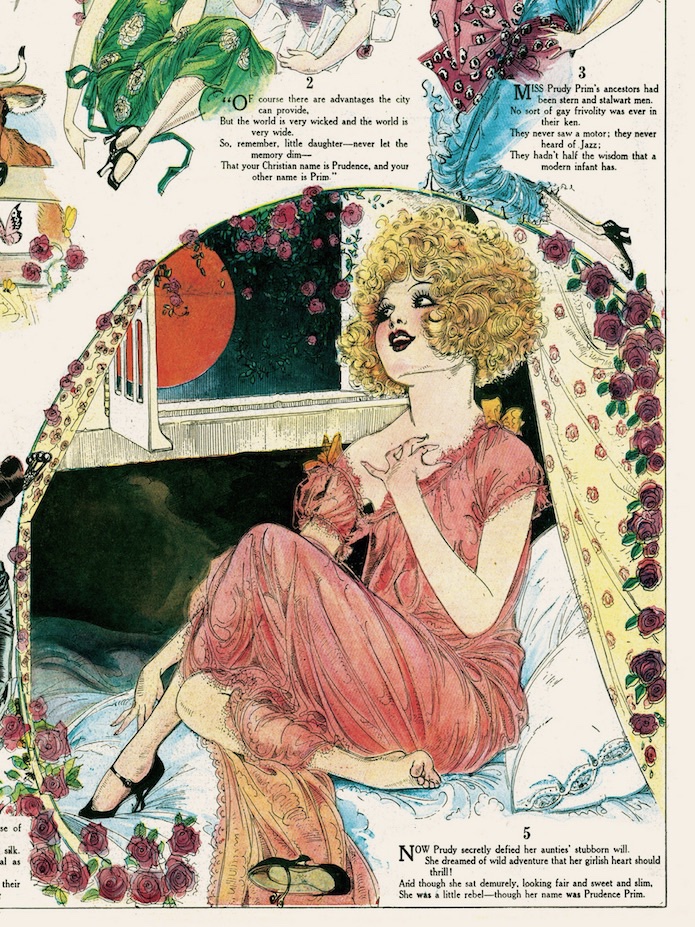

With a third of the book devoted to Brinkley, we get to see the most famous of female cartoonists evolve beyond the Gibson style into an Art Nouveaux and then Deco fine line work and precision. Robbins bookends the book with Brinkley’s changing views of American women, the artist’s criticisms of the very flighty flapper she celebrated in the 20s, and the active, engaged professional women she depicted in the 1930s.

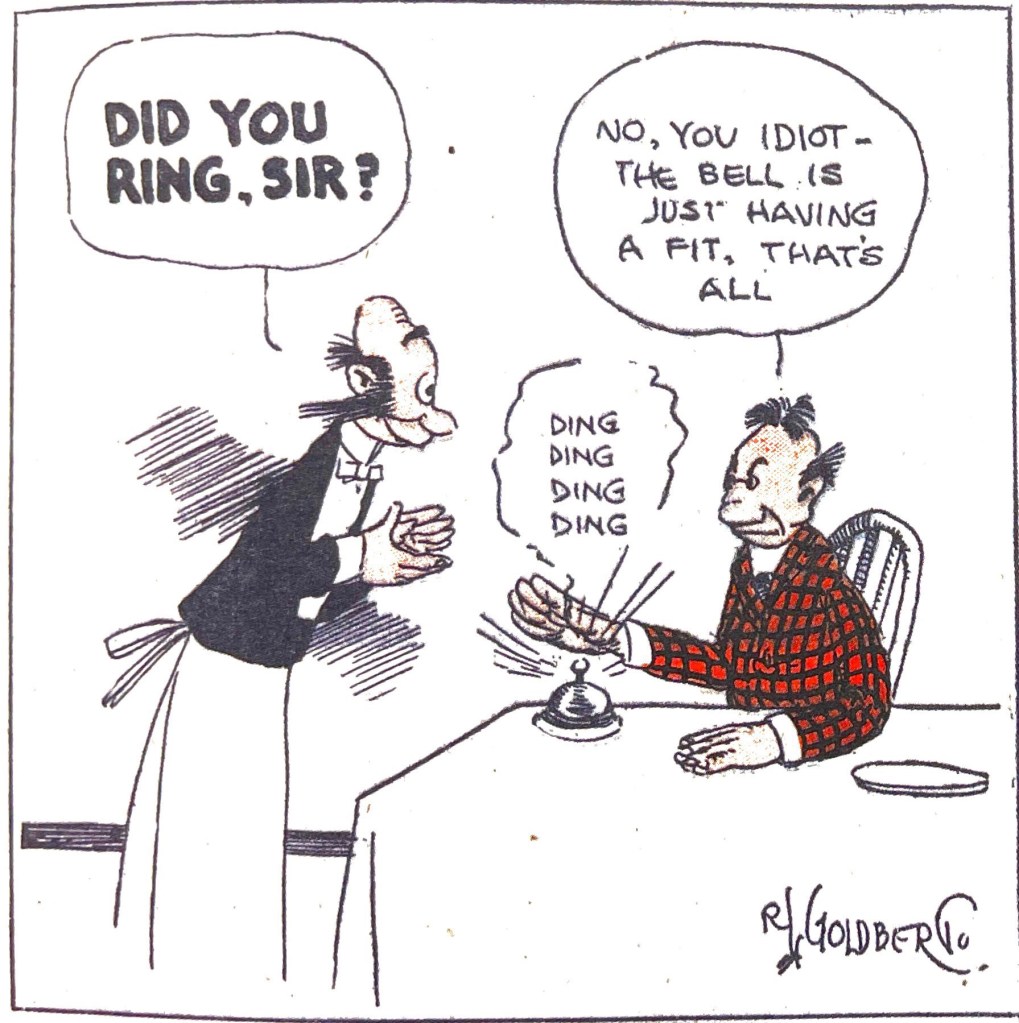

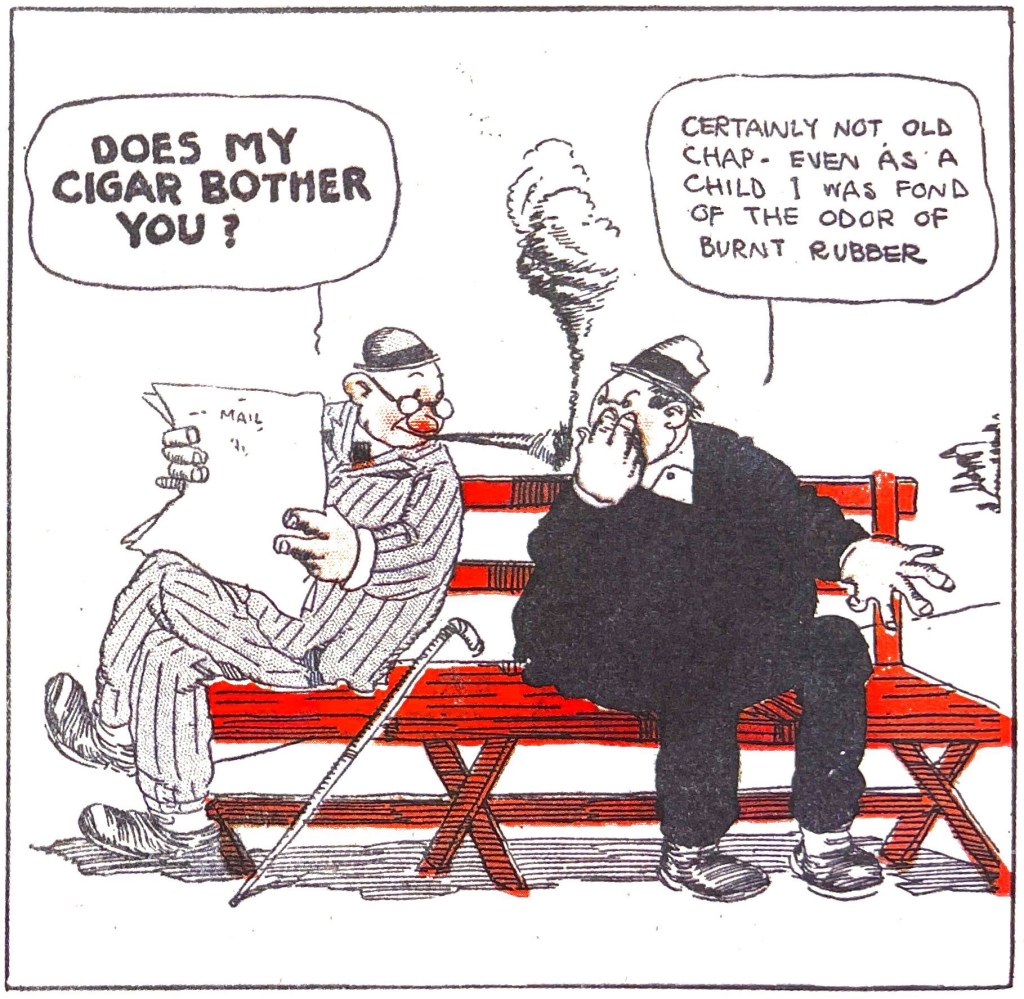

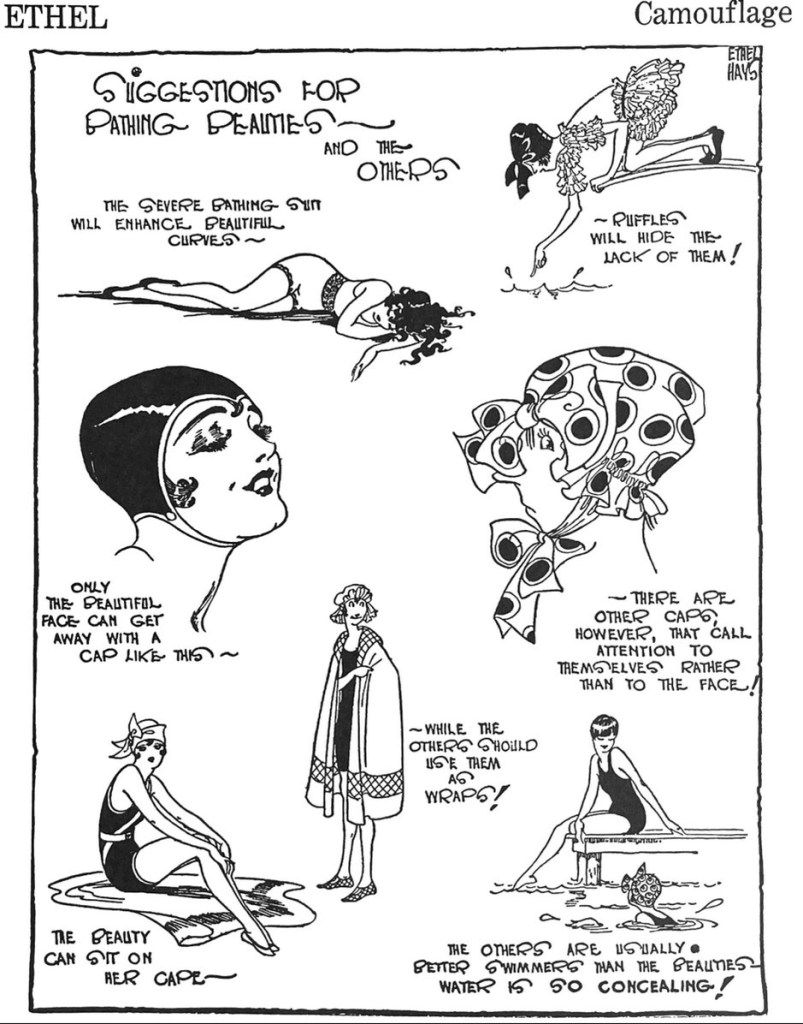

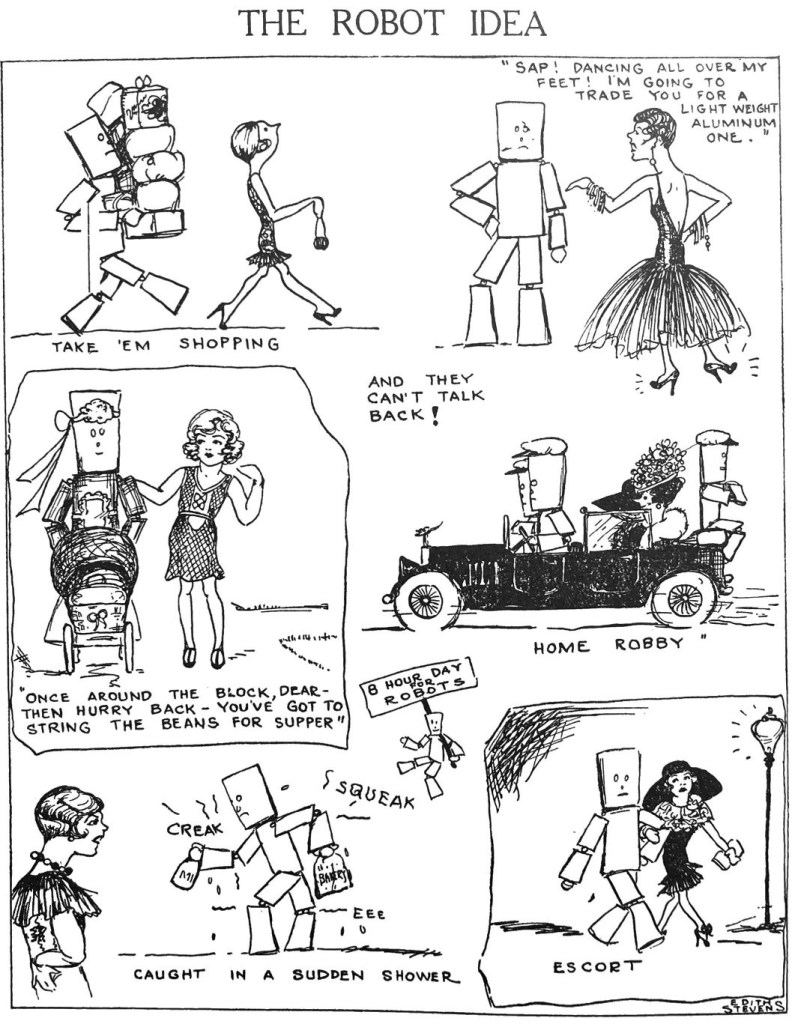

But along the way, Robbins gives us revealing samples across the careers of many women who continue to be overlooked by conventional comics histories. Edith Stevens’ Us Girls series blended fashion, biting wit and social observation in a series that was pithier and more insightful than many of the observational strips we continue to reprint elsewhere.

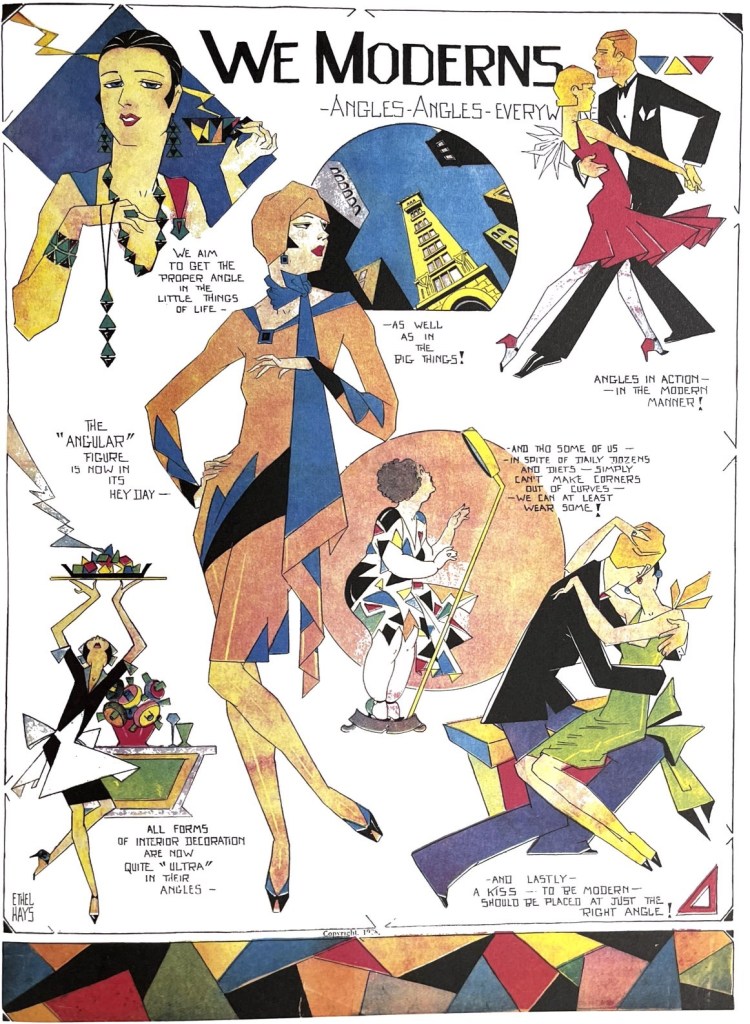

Robbins also focuses in on Ethel Hays, who channeled both Brinkley and John Held to chronicle the 20s and 30s in striking full page, richly colored Sundays that overwhelm the eye with color, a great sense of body angles and attitude. Like many of women in this book, she found creative ways to weave fashion styles, romantic advice, social commentary and a bit of cheesecake.

Hays’s “We Moderns” piece at the top of this entry is a great example of the creative richness and thoughtfulness we miss when, like their editors at the time, we consign women cartoonists of the day to the “fashion” artists bucket. Indeed, Hays, Brinkley and Huget not only paid attention to clothing, hair and even body styles, but they wove these concerns in with larger social, personal and aesthetic ideas. In “We Moderns” Hays actually brings these threads together in a startling visual think piece. She links the “angles” of modern fashion with architecture, clothing, dance, personal politics and even her own Deco-infused art style. Nell Brinkley was adept at using her characters’ clothing as instruments of drama, personality, reaction. They exploded from the page as effectively as her signature facial expressions – signals of inner-feeling. These artists didn’t just depict the visual styles and fashions of the inter-war years. They showed a rare understanding of why they mattered.

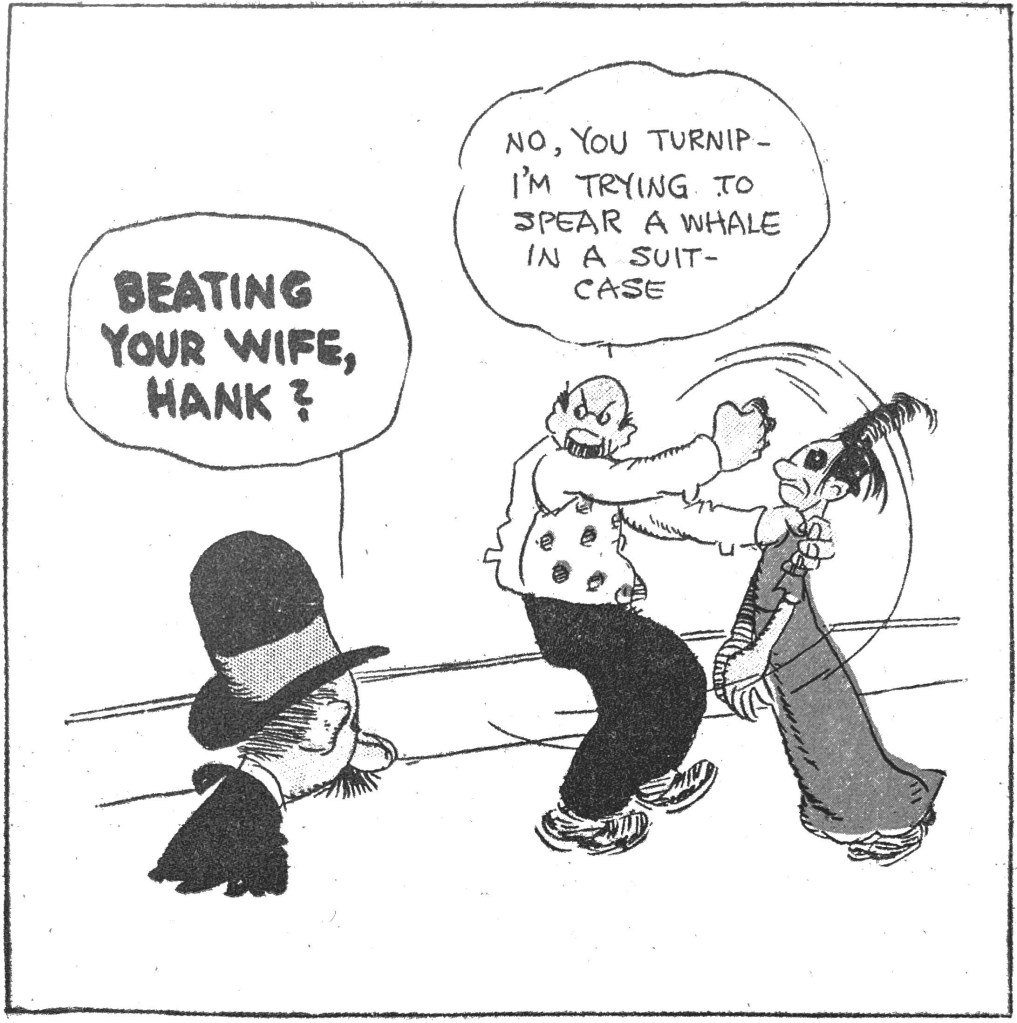

Fay King was perhaps the most socially engaged of the group, and her strips highlighted trends like women becoming more involved newspaper readers. Meanwhile Virginia Huget bridged the 20s and 30s with aspirational tableaux that romanticized college life and affluence. I also appreciated the inclusion of the wonderful Annabelle strips by Dorothy Urfer. This is a visually rich and wry look at sexual politics. It left me wanting mor.

And the reproduction/resotration work in Flapper Queens is superb, bringing forward the rich color and detail that made these images so absorbing in their time. Comics historians love to gush over the ways in which McCay, Feininger, King and the usual suspects among the kings of comics made innovative use of the full Sunday page, especially in the first decade of comic strip history. But the oversized, beautifully colored reproductions in this book show how artists like Brinkley, Hays and Huget especially burst from the Sundays of the 20s and 30s with dazzling uses of layout, splash images and narrative progression that rival and exceed many of their male peers.

Which brings me to the historical importance of Robbins’s Flapper Queens. Reviving these artists truly expands our understanding of comics history and especially the ways in which these very talented artists and social observers related to the surrounding culture between the World Wars. To overlook them is to miss some of the most striking art the comics were producing during this era. More to the point, these artists had a wry, sly and nuanced take on the politics of domestic relations. This book shouldn’t just “fill a gap” in comics history. It should make us broaden and reconsider the cultural work the comics were doing in American minds in the last century.

This is hands down my pick as the one indispensable addition to comic strip history in the last year.