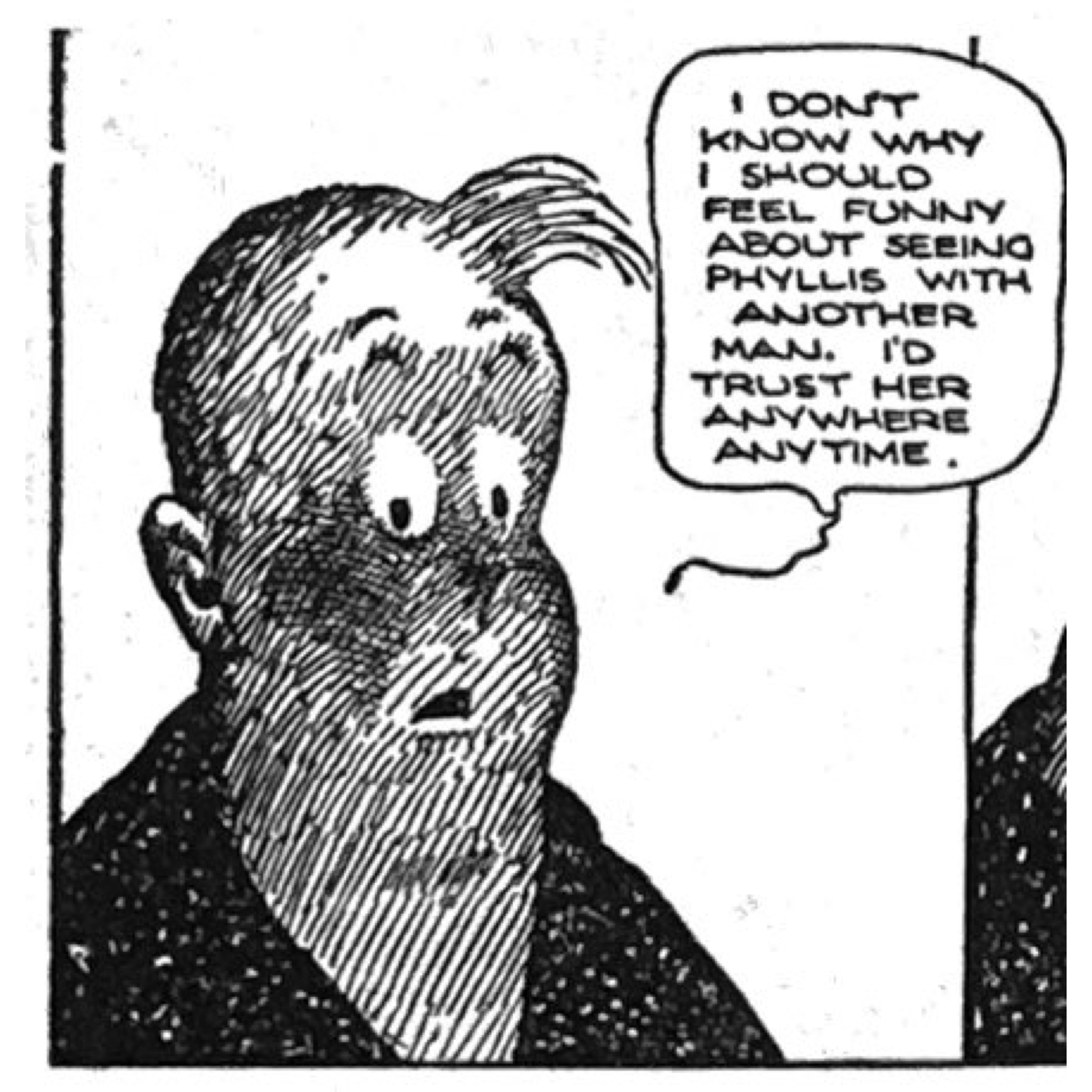

If you let the original art designer of The New Yorker loose on the Sunday comics page, then Rea Irvin’s The Smythes is pretty much what you would expect to get. For six years in the early 1930s, Irvin rendered the foibles and class anxiety of upper-middle class ex-urbanites Margie and John Smythe with impeccable Art Deco taste and reserve. Could we get anything less from the creator of Eustace Tilley, the monocled, effete and outdated New Yorker magazine mascot who appeared as the inaugural cover in 1925? Irvin was also responsible for the design motifs and even the typeface (“NY Irvin”) still in use at the fabled weekly. And The Smythes newspaper strip carried much of that magazine’s class ambivalence and self-consciousness, its droll observational humor, as well as its lack of real satirical edge. The Sunday feature ran in The New York Herald Tribune from June 15, 1930 to Oct. 25, 1936. It was among the most strikingly designed and colored pages in any Sunday supplement, even if its humor may have been too dry for most readers. Beyond the Trib, The Smythes only ran in about half a dozen major metros.

Continue readingTag Archives: comic books

Review: Emanata and Lucaflects, Blurgits and Maladicta: Mort Walker’s Lexicon of Comicana

Like the comics art it dissects, Mort Walker’s legendary Lexicon of Comicana is unseriously serious. It is a lighthearted, profusely illustrated breakdown of the visual language of comics, the tropes, conventions, conceits, cliches that artists use to communicate a range of emotions and personalities at a glance. NYRB Comics has reissued this hard-to-find 1980 classic with a ton of supporting material from Chris Ware and Brian Walker. It is a must-have for anyone interested in the medium.

Continue reading“Tycoons of Comedy”: Building the Myth of the Modern Cartoonist

“But the [comic] strip has suffered from mass production and humor hardening into formula…. It has sacrificed its original spirit for spurious realism.” – “The Funny Papers”, Fortune Magazine, April, 1933.

Who could say such a thing in 1933, just as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers, Tarzan and Terry were about to launch what many consider a “golden age” of American comic strips? But in a major feature in its April 1933 number, Fortune magazine lamented the new adventure trend as a sign of the medium’s decline. In their telling, comics were losing an antic, satirical edge that had distinguished them from the gentility of American literature or saccharine romance of silent film. In particular, the Fortune piece (unattributed so far as I could tell), bemoaned the rise of the dramatic “continuity” strip in place of gags. They single out Tarzan in particular as a corporate product that suffers from too many scribes and artists not working together. “The strip wanders through continents and cannibals with incredible incoherence,” they say. And to be fair, who could have foreseen in 1933 that Flash, Dick, Terry and Prince Val were about to redirect the “funnies” from hapless hubbies and bigfoot aesthetics towards hyper-masculinized heroism and a new realism that readers found far from “spurious?”

Continue readingReview: A Few Words on Anarchy: “Society Is Nix” Gets Shrunken Yet Enlarged (Updated)

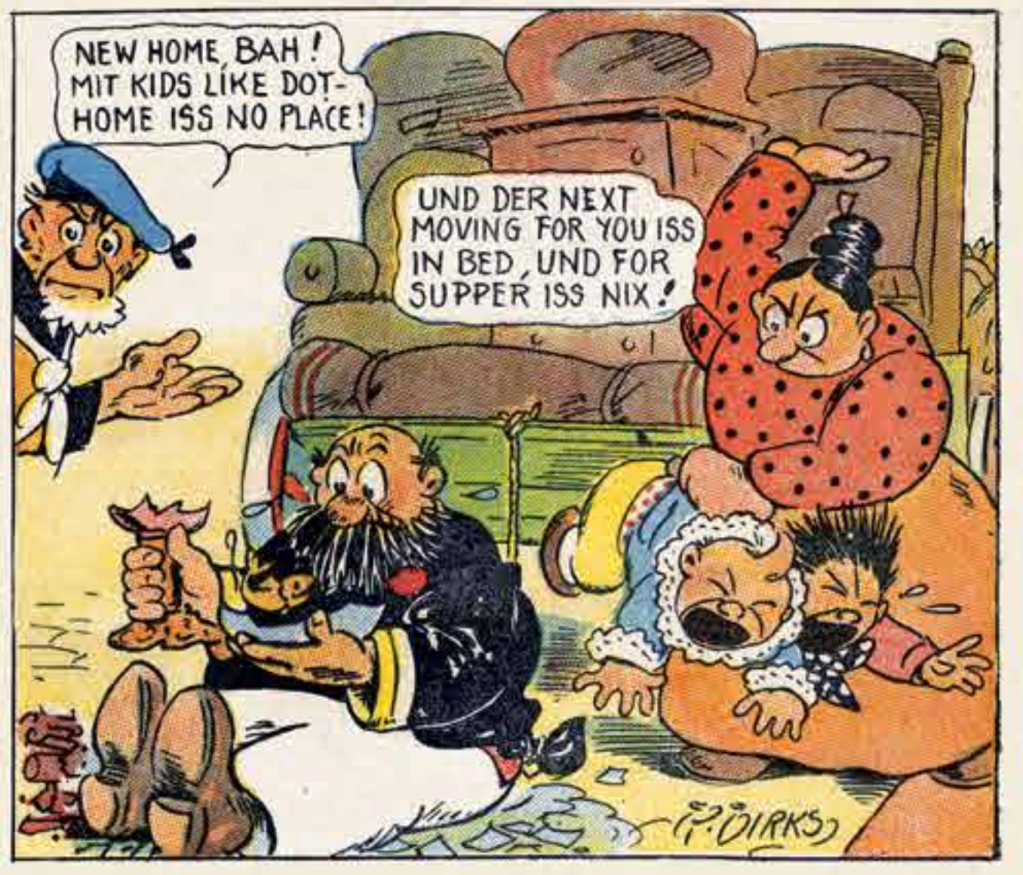

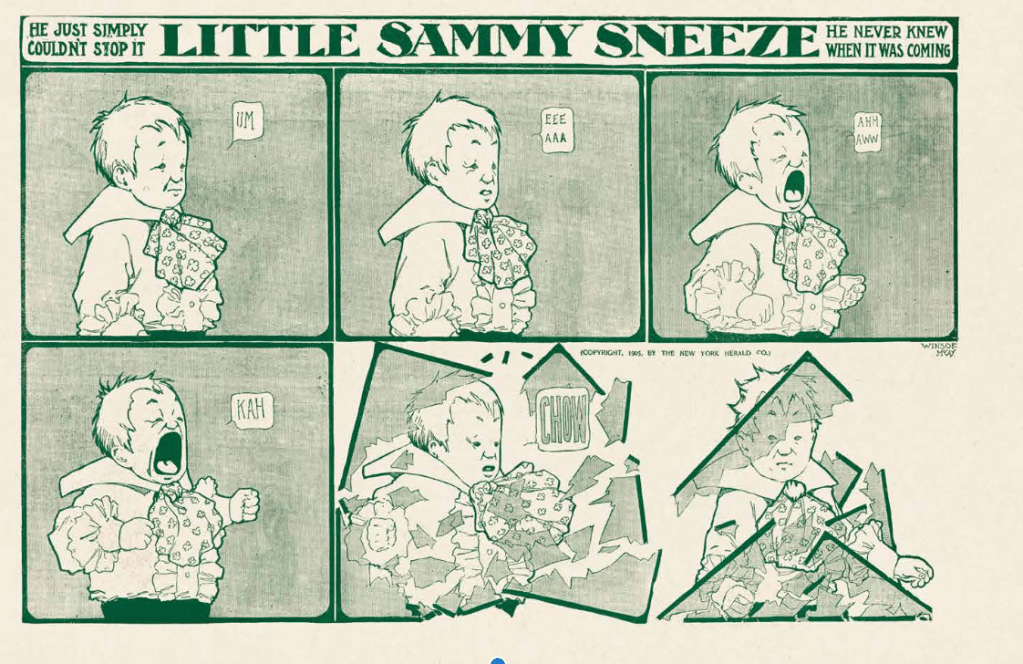

When the massive 21-inch by 17 inch, 152 page slab of early newspaper comic reprints bruised our laps in 2013, Sunday Press’s Society is Nix was a milestone. First of all, we had never seen so many examples from the innovative birthing years of the medium curated so intelligently, restored so beautifully and scaled to the original experience of the first Sunday supplements. Here we got that familiar crumbling mushroom forest in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, but now with the tonal nuance and size McCay intended. The Yellow Kid’s Hogan’s Alley was clear and detailed enough to appreciate all of that background business R.F. Outcault helped pioneer. We could best appreciate the sense of motion, and symmetry of Opper’s signature spinning figures in Happy Hooligan and Her Name Was Maude. And James Swinnerton’s often primitive-seeming linework revealed its expressiveness and intentionality when viewed closer up. Taking its title from a proclamation by the Inspector about the unruly Katzenjammers (“Mit dose kids, society iss nix!”), the book captured the creative freedom of a medium that hadn’t settled yet on a form, let alone a business model. Editor/Restorer Peter Maresca was unrivaled both in his eye for the right exemplary strip as well as his sheer skill in reviving the original color and detail from these yellowed, faded paper. For the last. Decade, Society is Nix remained indispensable for any fan or historian of the medium.

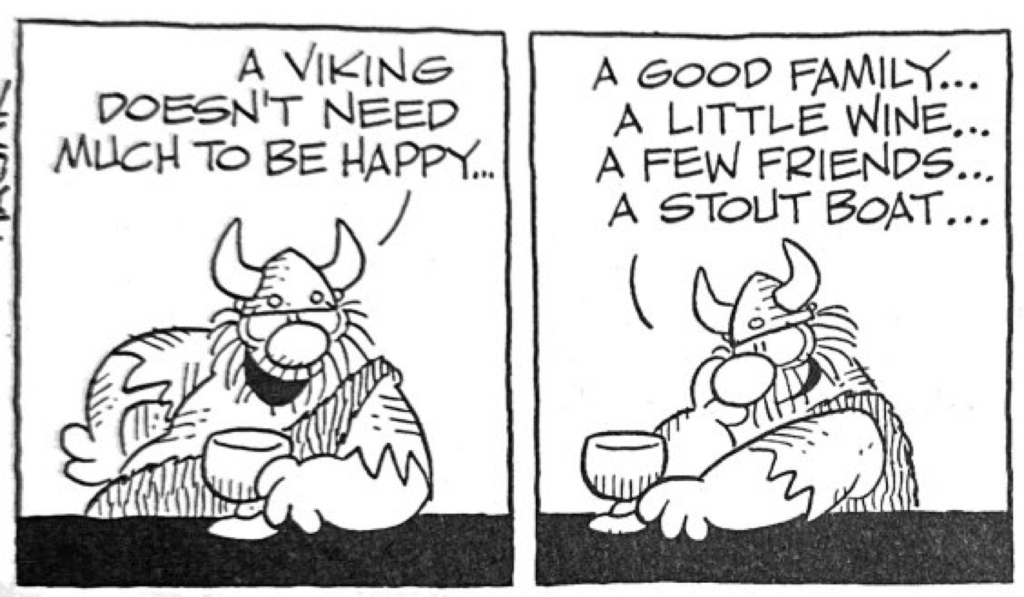

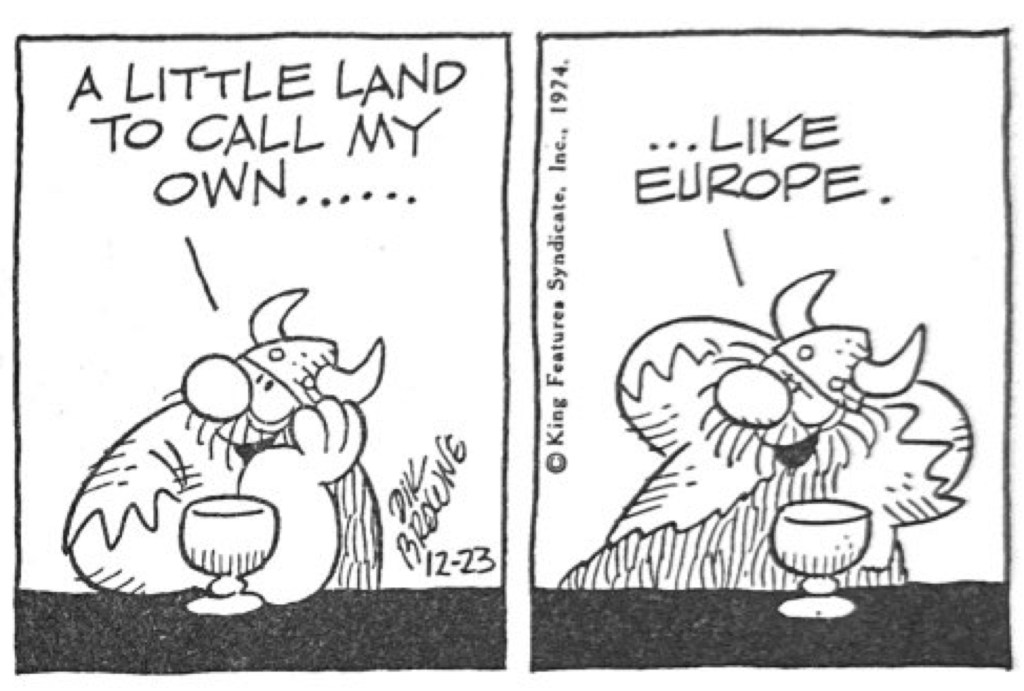

Continue readingThe Daily Anachronism: Fifty Years of Hagar

Like all of the most endearing comic strips. Dik Browne’s Hagar the Horrible came from a personal place. As Dik’s son Chris Browne tells it in the barbarian-sized collection, Hagar the Horrible: The First 50 Years (Titan, $49.99), the Brownes often joked about dad’s beefy, bearded, playfully irascible demeaner as Hagar-like. And it turns out, most of the eventual strip was loosely based on the character types and dynamics of the Browne household.

Continue readingGasoline Alley’s Emotional Realism

Frank King’s Gasoline Alley may be the “Great American Novel” of the 20th Century we didn’t know we had. This remarkable multi-generational saga of the Wallets evolved in several panels a day across decades, exploring the domestic and emotional lives of small town Americans during a century of intense change. And in its heyday during the post-WWI era, this strip was singular in its affectionate embrace of suburban family life at a time when post-war disenchantment overwhelmed the intellectual class, when glamour, sex and emotion dominated the film arts and magazines and glitz dominated Hollywood. When more famous social commentators like H.L. Mencken, Walter Lippman and Sinclair Lewis lampooned, decried and doubted the small town American intellect – the so-called “revolt from the village” – King celebrated what Mencken called the “booboisie.” Comics historians often characterize the post-1915 period of the medium as a kind of literal and figurative domestication. As newspaper syndication expanded into every burg, the mass media business of comics needed to shave the edges off of a once-raucous and urban-focused art form. Shifting the focus to family relations and suburbia, relying on more repartee than prankish violence, made the comic strip more acceptable to a mass audience.

Continue readingWhen Superman Was Woke?

America needed a hero. That is how Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster remembered the late-1930s world in which their modern myth soared. Everyone is familiar with the Clark Kent origin story: orphaned by cosmic circumstance; rocketed to Earth; fostered by the Kents in the american breadbasket; super-powered by our planet’s physics; and taking on his secret identity as the milquetoast reporter. It is that rare mass mediated pop culture fiction that genuinely approaches folk mythology. It is an origin that compels retelling for every generation. Less attention has been paid to his political roots, however. Every comic strip in the adventure genre especially has an identifiable political slant, most obviously in its choices of wrongs to right and the villains to subdue. The famously conservative Chester Gould in Dick Tracy and populist Harold Gray in Little Orphan Annie were the most overt. Less obvious was the implicit imperialism of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and most of the adventure pulps, which characterized non-Western cultures as at best quaintly primitive or at worst inherently brutal.

Continue reading