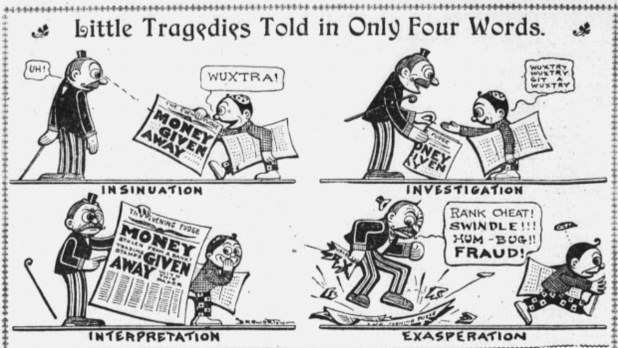

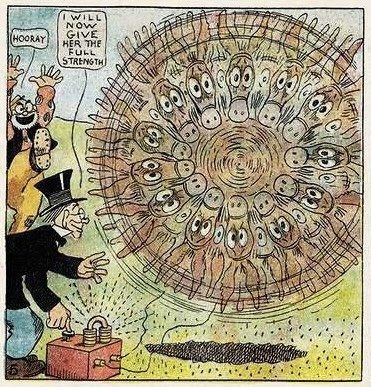

There were no firm rules for comic artists during that first 10 or 15 years of newspaper strips. Formats, aesthetic conventions, even panel shapes and limits hadn’t been fully established. The medium was still elastic. And so we see in these years wild experiments in artistic styles, unfettered explorations of page and the panel structures, even testing different interactions of words and image. Little Tragedies Strikingly Told in Four Words contains that spirit in its own title. It frames itself as an experiment. Crafted by the otherwise forgettable Alfred W. Brewerton for the New York Evening World between Oct. 1903 and June 1904, it was an unusually long-lived title to appear several times a week. True to its title, the strip is indeed striking because it blends pantomime and text in a novel way that is also compact, highly stylized, even wry. It recalls that famous quip about Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy being easier not to read than to read. And like Nancy, the strip gets at something elemental about how comics work.

Continue reading