I am an EC chauvinist. I should cop to this before rounding up the notable pre-code comic book reprints from the last year. For decades now I have been devouring the many crime, horror, sci-fi, and romance comics that were part of the glut of adult titles after WWII, in part because they represented the unrealized potential of the comics format in post-war America. This was a real pop culture moment. War veterans ate a steady diet of comic books “over there” and seemed primed to follow the medium into more nuanced and adult storylines in the 40s and 50s. Likewise overseas, Japanese manga and Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées were on a similar path towards the popular, if not literary, mainstream. But in the U.S. that evolution was derailed and slammed into reverse by anti-comics crusades and the industry’s own “Comics Code Authority” in 1954. Self-censorship effectively arrested the medium in pre-adolescence, focused the industry on anodyne morality tales and pubescent fantasies of super-human prowess for at least a couple of decades.

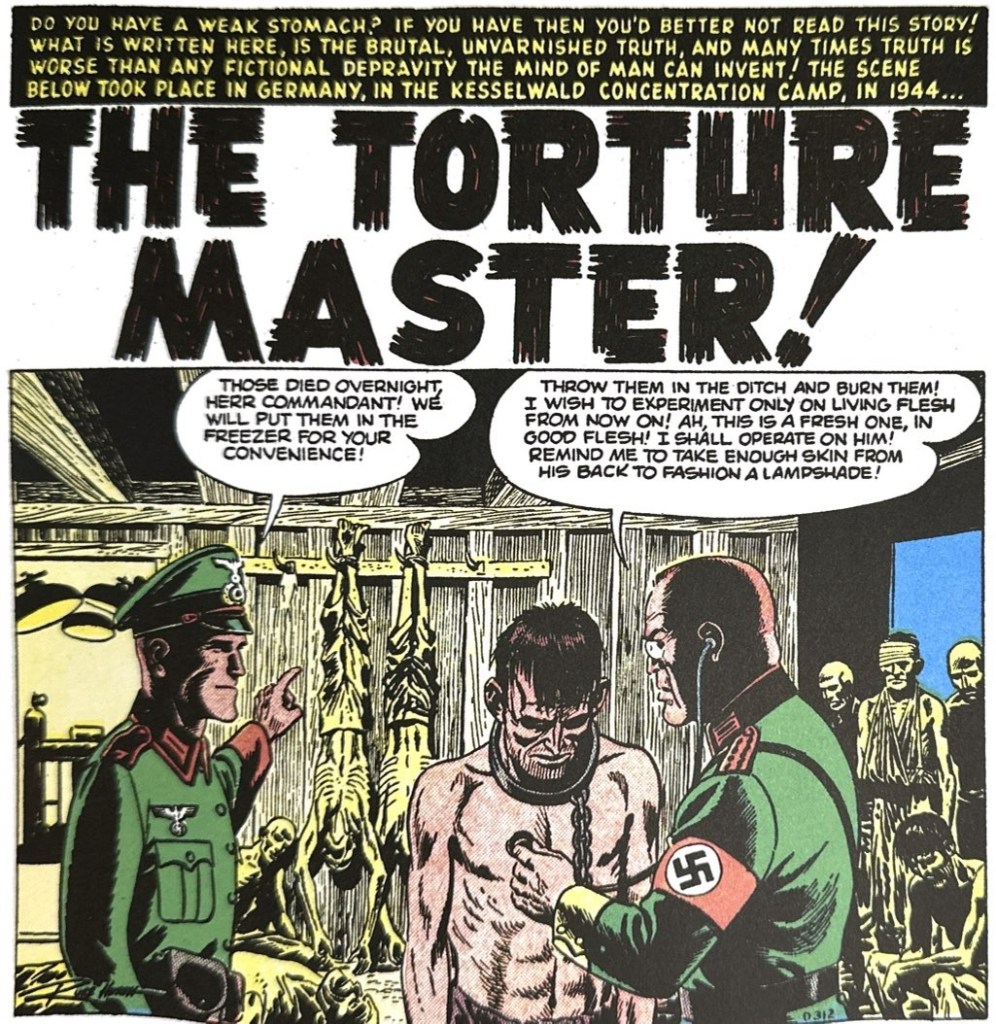

In my mind, the stable of writers and artists at Bill Gaines’s EC Comics not only represented the pinnacle of that pre-code promise, but they left most imitators in the dust. That is not to say that Atlas/Timely, Fiction House, ACG, Gleason, and many other publishers didn’t have their moments. But they were wildly uneven. Collectors and completists may enjoy the full run reprints of these titles from PS Artbooks and the Fantagraphics series of early Timely/Atlas titles. Personally, I find it hard to thrash through so much hack art and risible writing. I much prefer cherry-picked anthologies like IDW/Yoe Books’ themed compilations, especially their Fiction House collection. Also, for those who want to cut to the chase, and cut out the dross, I would recommend Jim Trobetta’s The Horror, The Horror (Abrams Books) and Greg Sadowski’s Four Color Fear (Fantagraphics).

Still, I was looking forward to Volume 7 of the Atlas Comics Library series of Girl Comics. It is a part of the ongoing micro-history of pre-Marvel Atlas books selected and restored by Atlas expert Dr. Michael J. Vassallo. Comics historians tend to minimize or overlook the massive appeal of the romance and girl adventure comics of this period, in favor of the more boyish crime, war and horror genres. And so, this massive 397-page reprint of the first 12 issues of a comic that evolved from classic romance to empowered girl adventure seemed most welcome. Well, until you slog through it.

The first five or six issues of Girl Comics were riding off of the “love glut” of romance comic books during the late 1940s. As Vassallo reports, romance may have been the most popular pulp fiction genre of the 1930s and 40s, peaking with Street and Smith’s Love Story. So, when Simon and Kirby energize these themes as dynamic comic art in Young Romance (1947) the market in love explodes. It then collapses from oversaturation into a smaller circle of titles after 1950. Timely itself had 44 titles by Vassallo’s count. Girl Comics survived the transition in part by pivoting to an adventure motif from issues 6 or 7 to 12. In principle, Girl Comics should be an interesting example of pre-feminist female empowerment, which Fantagraphics teases in the book’s promotion.

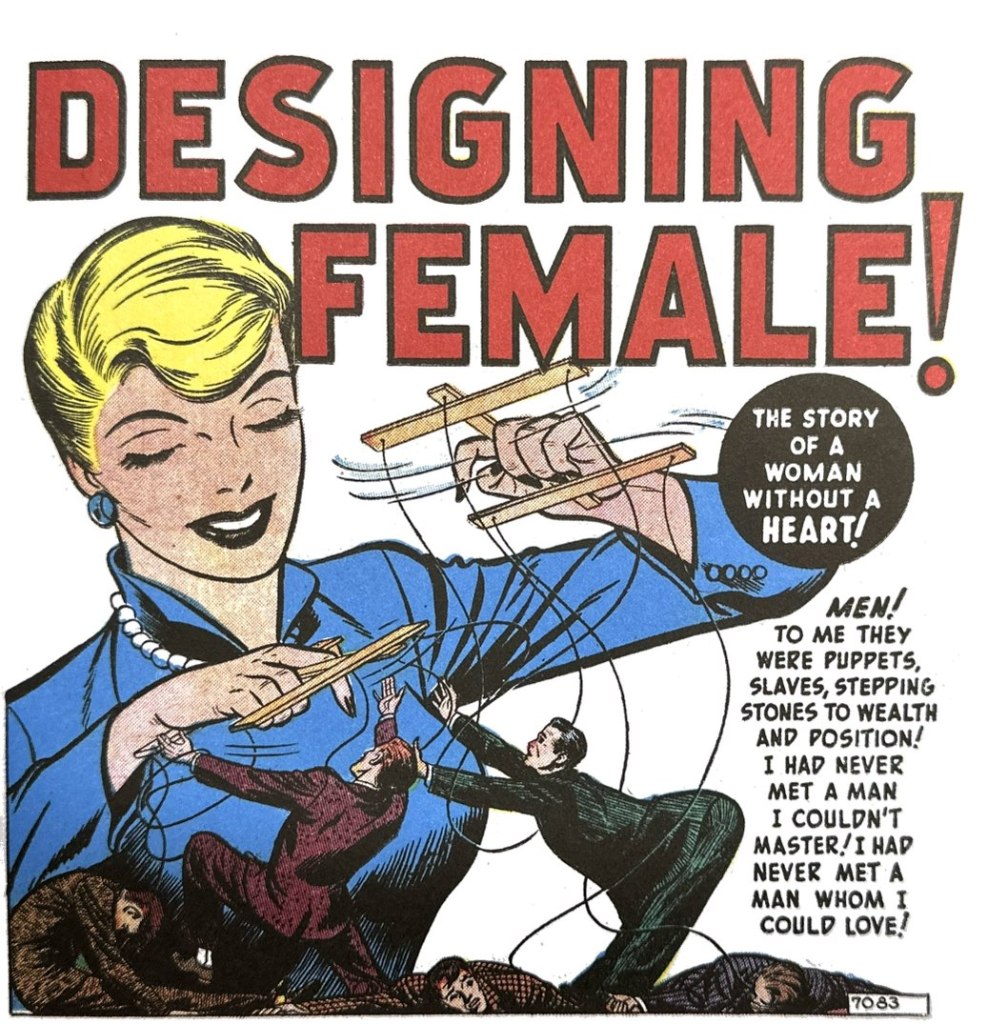

Alas, neither the scripts nor the art demonstrated any mastery of either genre. Most of the love stories deal in very low stakes with muted emotions and anodyne art. The romance themes are familiar. Affluent girls fall for working class guys, who eventually reveal as rich. Betrayal by sister/best friend rivals where straying men return to our heroine. Falling for a blind man who of course gets his sight back. Etc. Which is fine. Formulas are interesting in and of themselves. But the art of romance is to use graphics and dialogue to make small events deeply felt – small stakes that feel big. Most of the scripts are unattributed, and understandably so. The art, while done by some great pros like Bill Everett, Joe Maneely, Russ Heath and Mike Sekowsky rarely depict the facial expressions, state of mind, body posture in ways that raise the stakes. The shift to adventure stories is no better. Our heroines usually are low level clerks, government functionaries and assistants who get caught up in spy or crime plots. Reading these scenarios as somehow upending the genre and empowering women is a stretch. Worse, the art is unengaging. Even Bernie Krigstein takes a turn here, but he finds a way to reduce an adventure into panels of talking heads. And while Girl Comics advertised its later issues as “Real Adventure for Real Girls,” the series veered back to bad romance and using its confessional tropes to frame its thin adventures. Some panels, splashes and sequences that show whiffs of flair, but generally it feels as if the artists are working down to the quality of the writing rather than up from it.

There are some wonderful reprints and reflections on women in pre-code comics, namely Romance Without Tears, the Young Romance reprints and New York Review’s excellent Return to Romance. Some notable auteurs like Ogden Whitney, publishers like Archer St. John, and art stars like Frazetta, Wood and Baker showed a genuine understanding of the genre. And even this Girl Comics collection has a couple of memorable stories, like the “Designing Woman” tale with a great Sekowsky splash panel and solid morality tale of blind ambition. But generally the problem here is perhaps the greatest sin in mass media, producers who don’t really respect the genre they are exploiting.

Marginally better is Volume 5 of the Atlas Library, Police Action!, where Vassallo samples the publisher’s massive crime comics output by highlighting full issues of Police Action and Police Badge titles. They include early decent work from Joe Maneely, Gene Colan, Don Heck and Bob Powell. While far from innovative or compelling, at least here the artists and mostly anonymous writers were able to draw from a richer pool of stronger competitors in the genre. Colan’s rendering of a rookie cop’s first eventful day is energized by his strong panel breakdowns and action figure drawing. Powell’s mastery of cartoonish expression and caricature is perfect for a story about a thug who always seems to have an alibi. And Maneely shows a touch of EC gothicism in a story about a rapacious hound in 1890s London. But generally this is all workmanlike b-grade comics fare mainly for those who regard this sort of thing as comfort food.

Occasionally interesting is Atlas Library Vol. 4, War Comics. This long running title was a direct response to the start of the Korean War, and most of the unattributed storylines are boilerplate combat valor pieces or outright propaganda. While Vassallo argues that this title had some of the famously anti-war vibe of Harvey Kurtzman at times, you have to squint to see it. Russ Heath’s work is the only standout here. He clearly is bringing over to War Comics the desolate feel of the battlefield as well as Kurtzman’s propulsive action breakdowns. And across these artists, some of whom themselves experienced war, specific panels capture an authentic violence and grisly impact of battle. But generally, this is a case where a “best of” collection of really strong work across the other Atlas war titles would be much more satisfying. And to be fair, I gather that these volumes are aimed at completists and collectors who like to feel as if they are perusing original issues.

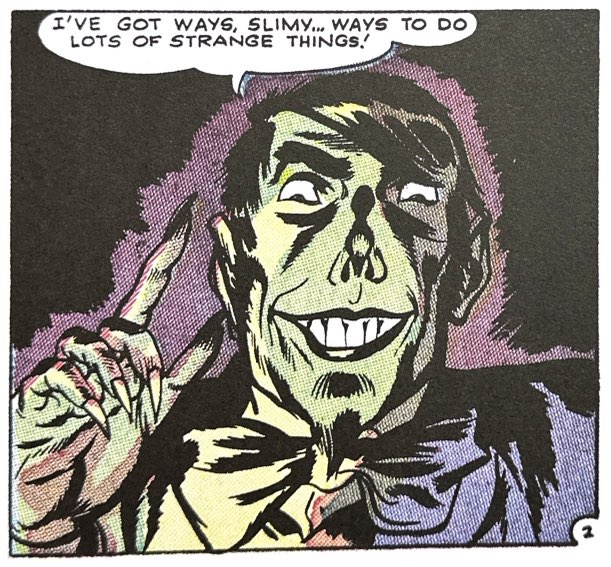

But before it appears that I am being too critical of this generally fun Fantagraphics project, I should single out its strongest releases this year. Volume 6, Shiver As You Read! captures issues of Amazing Detective and Men’s Adventure when both titles turned to horror with very good effect. We get little gems like George Roussos doing a highly stylized supernatural tale of a gangster faking his death to overhear the mourners. Or Bernie Krigstein flexing his blotchy lines, panel progressions and light-sourcing muscles to elevate a silly story of a convict who can morph into a rat. The “Gorilla Man” is the sort of bonkers body dysmorphic nightmare that deserves Robert Sale’s in-extremis style of terrorized close-ups, screaming text, staccato pacing. Campiness is one of the true pleasures of good Pre-Code comics, and this volume carries that vibe more consistently than any I have seen in the Atlas reprint series. This may be in part because many of these issues come later than the other volumes (1952-1954). By this time the visual tropes of the horror genre had been well established across publishers and increasingly experienced artists like Maneely, Crandall, Infantino, Heath and Sinnott were raising the bar on each other.

Speaking of peaking talent, the crown jewel of this year’s Atlas Library series is its Artist Edition No. 2 devoted to Al Wiliamson. Technically, this book is not “pre-code,” but who cares? It is a visual treat. Fantagraphics has compiled over 400 pages of Williamson’s complete work for Atlas, mostly westerns but also jungle, horror, suspense and war genres. After the collapse of EC’s New Trend titles, where he did stellar work especially in sci-fi, Williamson freelanced extensively for Atlas between 1955 and 1960. While the scripts were tamer and more contemplative in these post-code years, often boilerplate morality tales, Williams’s signature faces and bodies made them kinetic. Few artists worked tepid scripting so hard to find emotional energy through panel progression and composition, eye-talking and gesture. In many cases, the episodes are better experienced without actually reading them. Williamson finds a greater depth of feeling and conflict in these characters and situations than the writer did. In simple gunfighter tales like “The Death of Dalla Dawson” his tight clusters of faces establish a dynamism that is richer in fear and determination than the verbal exchanges. His Jann of the Jungle tales bring us into the jungle environment so effectively the reader feels poised to trip over a vine. My only quibble with this enormous (both in page count and oversized scale) treasure is that we miss some of Williamson’s fine line work. Working necessarily from scanned original comic book pages, and enlarged nearly to 10×14, some of the repros feel blotchy compared to the Williamson we see in EC reprints like 50 Girls 50. But for fans of 50s comic art, this is the one to get.

EC Great and Small

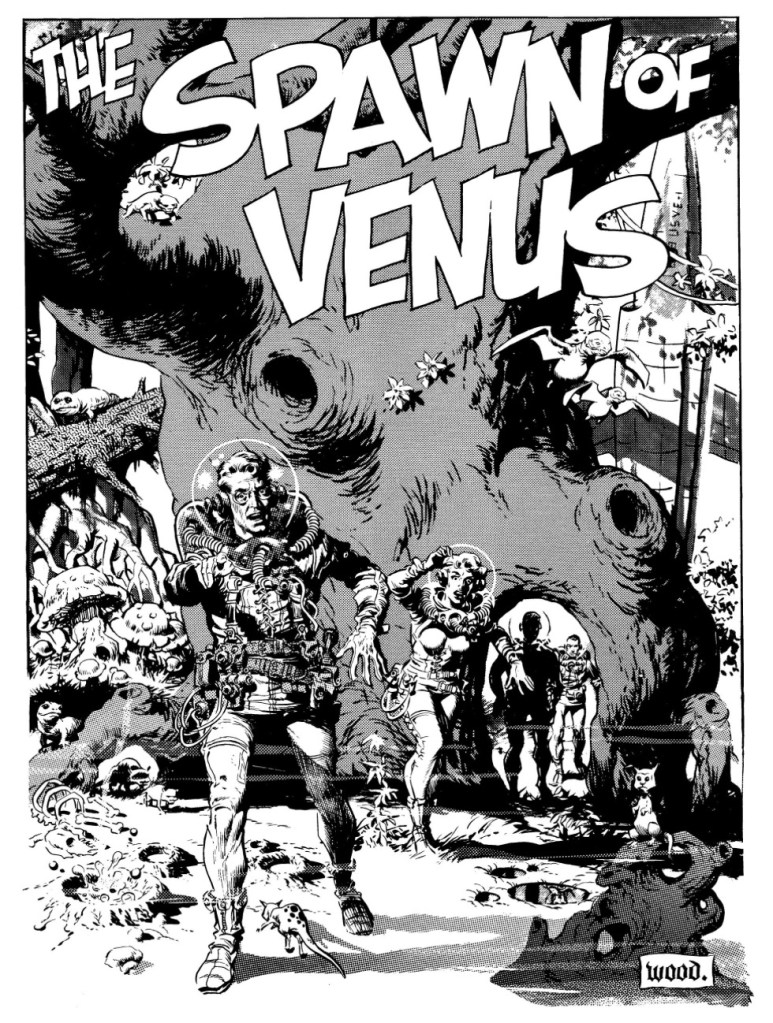

You don’t need to be an EC completist to crave Spawn of Venus and Other Stories, which collects some of the best Wally Wood sci-fi work in the black and white EC Library series. What Williamson was to facial expressiveness and kinetic figure drawing, Wood was to futuristic environments. His use of techno-clutter, selective detail, deeply inked shadows and alien landscapes created a visual language for the sci-fi genre. He had a way of rendering rocket ships and half-clad women with a similar eroticism. There was no one quite like him. This volume includes a previously lost and censored page from “You, Rocket” and a 2-D version of the unpublished 3D story of the title, Spawn of Venus. And as with all of these Fantagraphics EC Library books, the pristine source material, left uncolored, showcases the detail and care that each featured artist brought to the work. EC distinguished itself among other comics publishers, including Atlas, with an absence of cynicism. Al Feldstein and Bill Gaines enjoyed and respected the genres their New Trend books explored. The artists responded accordingly.

While Wally Wood should appeal to anyone interested in fine comic art, Dark Horse’s EC Archives volume of The Complete Moon Girl is for EC obsessives only. Covering the 1947-1949 lifecyle of this Wonder Woman-ish superheroine, we get a lot of mediocre art from Sheldon Moldoff and Johnny Craig off of Gardner Fox’s ham-handed scripts. Of uncertain origin and with variable powers and vulnerabilities, Moon Girl and her partner Prince Mengu have vague mythological roots. There is a “moonstone” that confers special powers, a generally progressive social outlook that aims to improve mankind, a lot of pleas to “Jupiter” and other gods…. Yadda yadda. The best that can be said of this series is that Fox seemed to have a few interesting story concepts, but the execution flags. A recurring villainess Satana could have been interesting, but she generally is just a gangland leader. One promising story has her inciting racial and ethnic hatred in a multi-ethnic neighborhood, but it is never really explored. In another, a conspiracy to replace the patriarchy with all-female governments can’t even muster up a rationale or back-story like, well, good old-fashioned man-hating? Like too many of the lesser superhero books of the era, Moon Girl never develops a character, her exploits are all over the genre map, and the story progression and turns of fortune seem nonsensical.

A lot of the Pre-Code comics reprinted this year raise the obvious question of how much of this we really need? The natural answer for a consumer culture like ours is, well, as much as the market will bear. If some readers, collectors, completists continue to get joy from recreating the experience of post-WWII comics, then have at it. Which is fine. Who am I to rain on the parade? Well, I am a pop culture critic and historian, and I believe that enjoyment of a medium is enhanced by deciphering its joys and strengths and discriminating between the good and the bad. It deepens our pleasures and heightens our impatience with mediocrity.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks so much for this concise summary. I’m glad someone is doing this; I’ve been on the fence about a couple of these.

Thanks. Glad it helped.