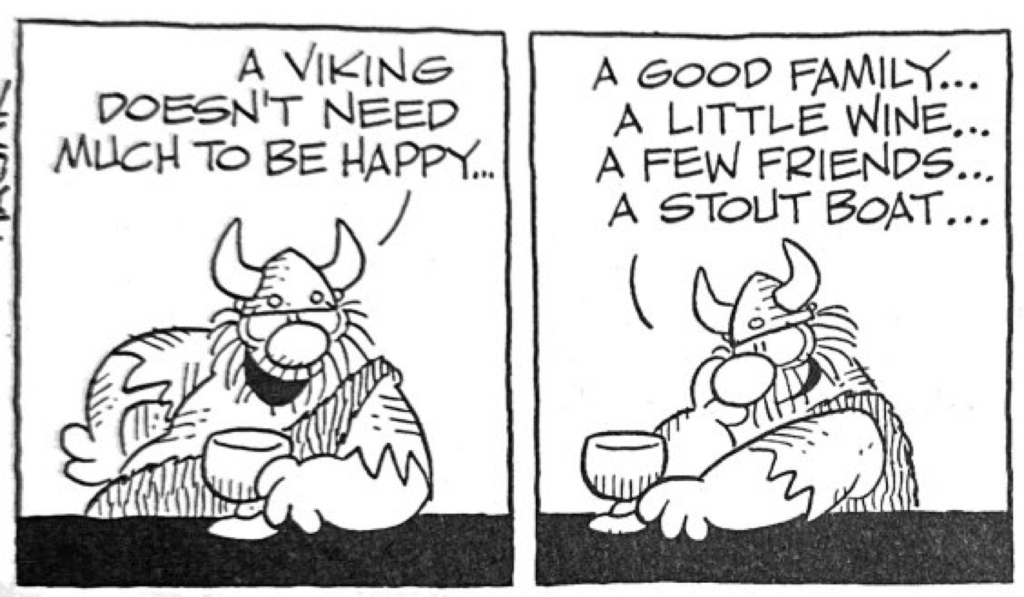

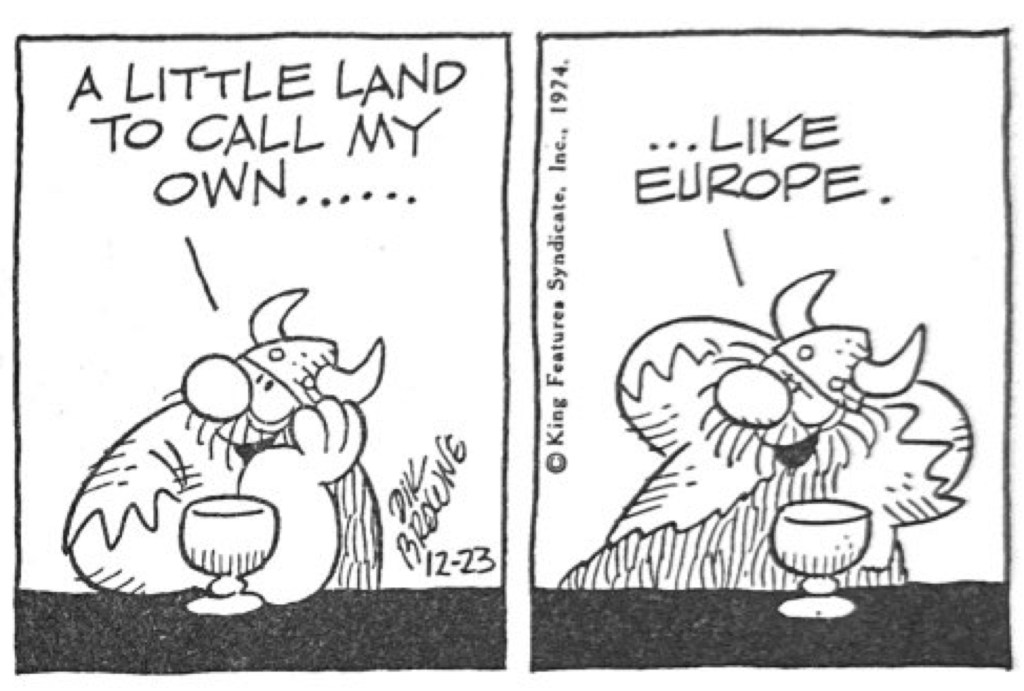

Like all of the most endearing comic strips. Dik Browne’s Hagar the Horrible came from a personal place. As Dik’s son Chris Browne tells it in the barbarian-sized collection, Hagar the Horrible: The First 50 Years (Titan, $49.99), the Brownes often joked about dad’s beefy, bearded, playfully irascible demeaner as Hagar-like. And it turns out, most of the eventual strip was loosely based on the character types and dynamics of the Browne household.

Continue readingTag Archives: comics and culture

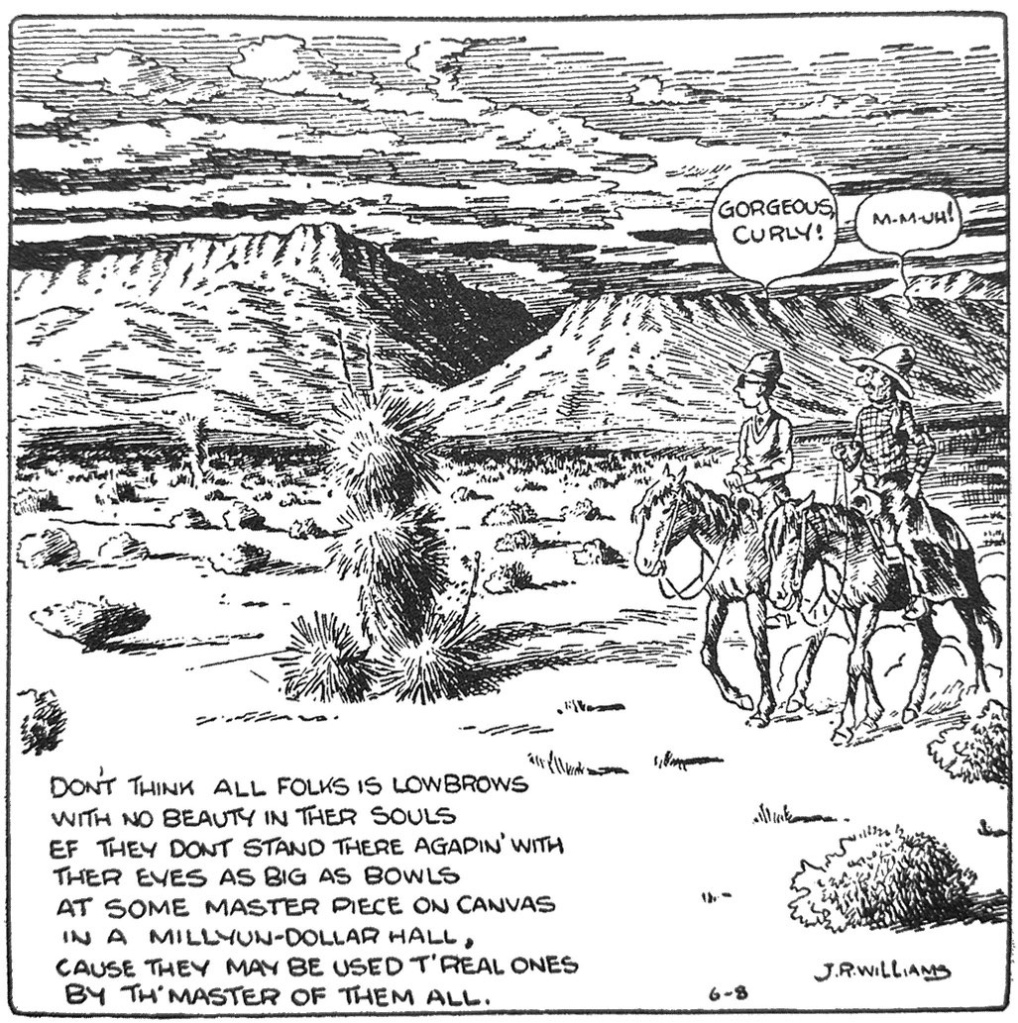

Cartooning the ‘American Scene’: Comics as Modern Landscape

We are such suckers for highbrow validation. Sure, we pop culture critics and comics historians talk a good game about bringing serious critical scrutiny to popular arts, our respect for the common culture…yadda, yadda. But our pants moisten whenever the intelligentsia deign to take our favorite arts seriously, or we find some occasional reference or connection between the “high” and “low” culture labels that we claim to disown. Comic strip histories love to gush over Cliff Sterrett’s appropriation of Cubist stylings in Polly and Her Pals. Although his dalliance with cartooning was brief, Lyonel Feininger’s Expressionist turn in the Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie loom so large in comics history you would think he was a beloved mainstay of the Sunday pages. In face, he was a fleeting presence. Picasso’s devotion to the Little Jimmy strip suggests somehow that Jimmy Swinnerton was onto something deeper than it seemed. And of course the critical embrace of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat started early, when Gilbert Seldes and e.e. Cummings, among others, primed us to believe the greatest of all comics for its surreal aesthetic and mythopoeic narrative.1 Never mind that the strip suffered limited distribution and perhaps narrower audience appeal. Indeed, an entire scholarly anthology, Comics and Modernism is a recent map of all the ways in which comics studies tries to wrap the “low” comic arts in the (to my mind) ill-fitting coat of high modernism.2

Continue readingSwipe-Right Follies, Circa 1904

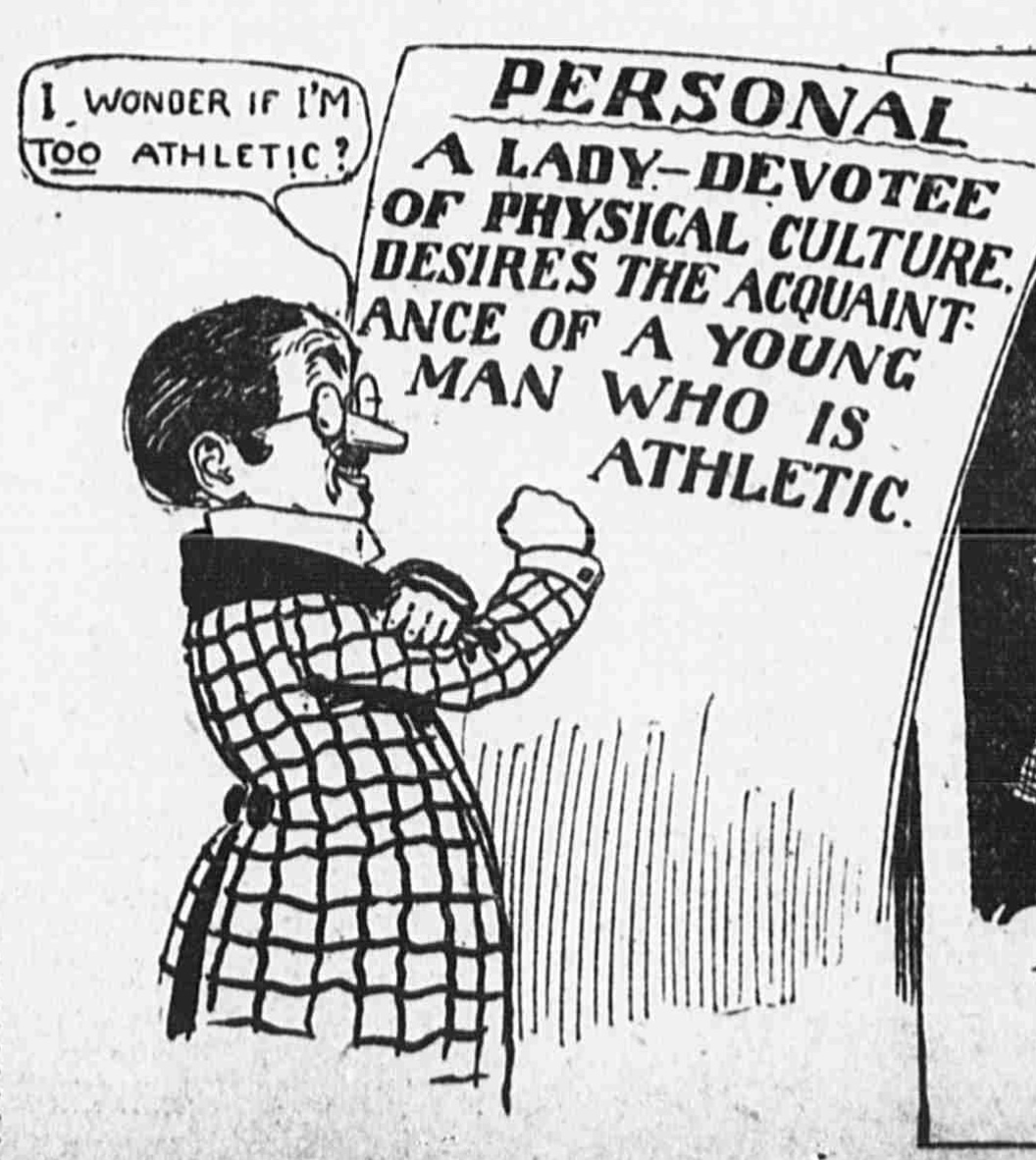

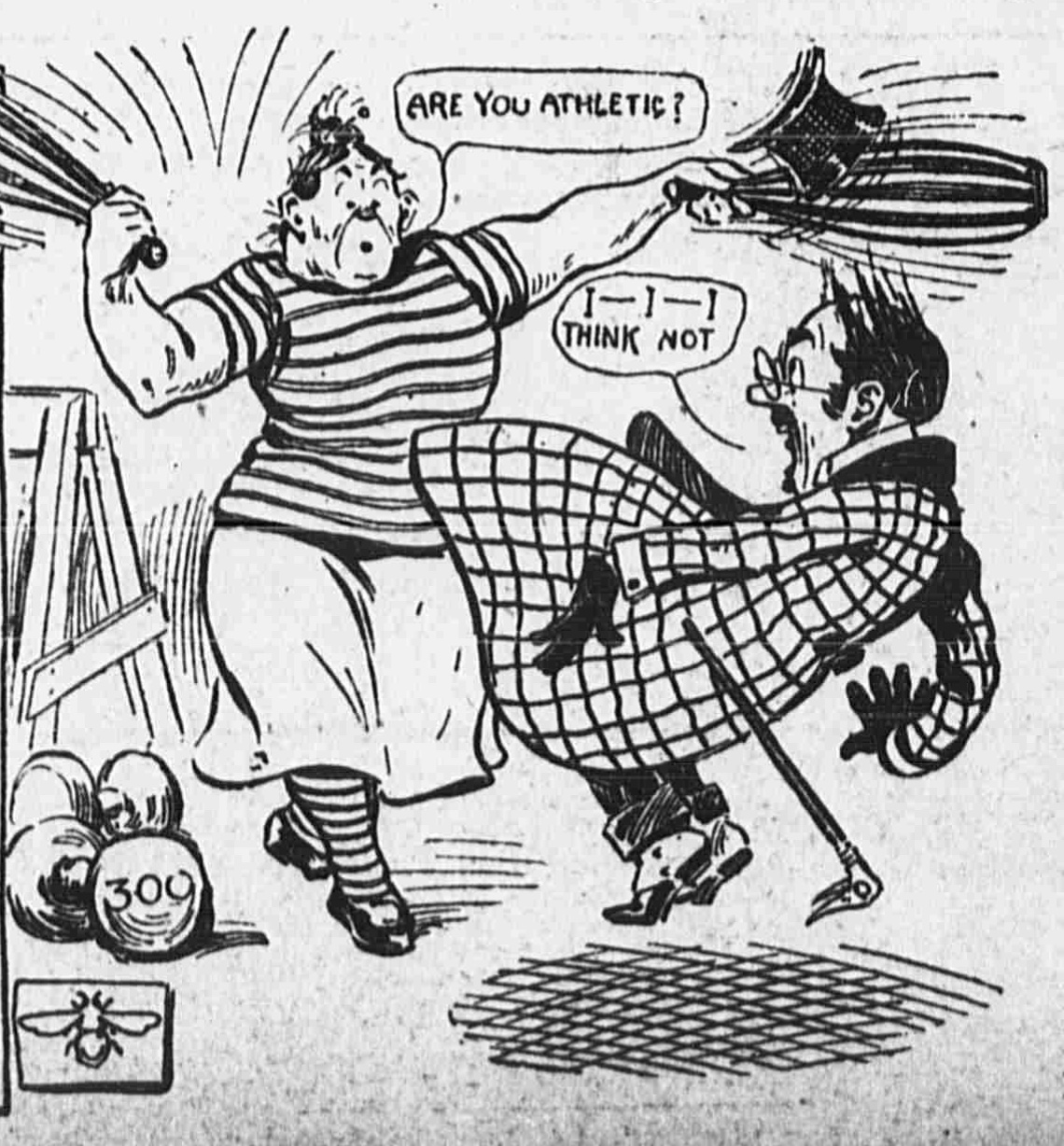

Apparently, getting a date was never easy, and the contemporary swipe-left, swipe-right mobile media is just the latest twist on an old genre – the “personals.” This short-run comics series of 1904, “Romance of the ‘Personal” Column,” in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World reminds us that Americans were already jaded about the deceptiveness of these early versions of the dating app over a century ago. The strip followed a familiar formula. Our misbegotten suitor finds that the reality of his blind date is frighteningly different from his impression of the ad. Thus, he flees in panic; from a widow’s horde of kids, a muscle-bound athlete, and, in a racist turn that was standard in the day, a “dark brunette” who turns out to be Black. “Romance of the ‘Personal” Column” only ran a handful of times, but it is the kind of early comic strip trifle that surfaces a number of important themes in the cultural history of the first newspaper strips.

Continue readingGasoline Alley’s Emotional Realism

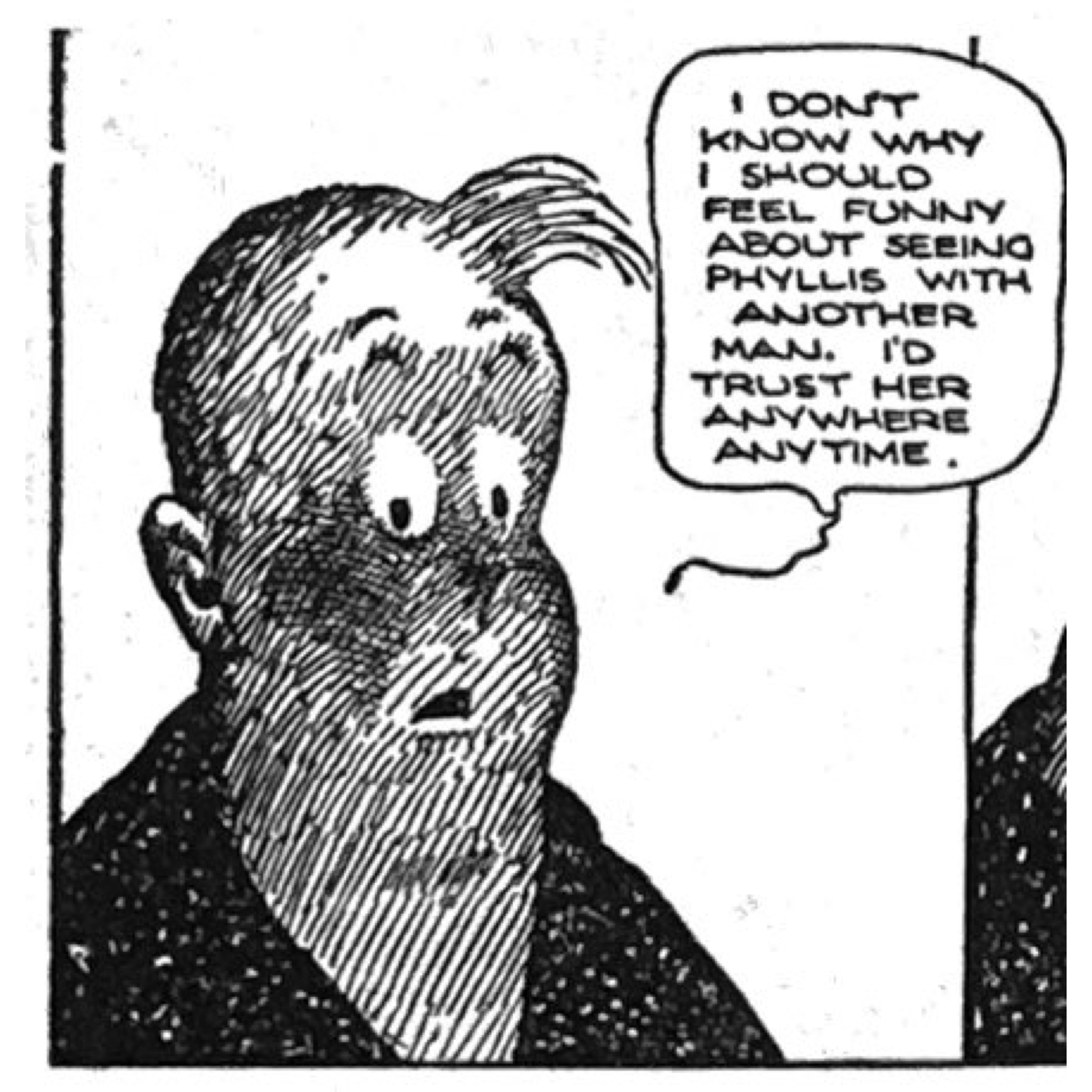

Frank King’s Gasoline Alley may be the “Great American Novel” of the 20th Century we didn’t know we had. This remarkable multi-generational saga of the Wallets evolved in several panels a day across decades, exploring the domestic and emotional lives of small town Americans during a century of intense change. And in its heyday during the post-WWI era, this strip was singular in its affectionate embrace of suburban family life at a time when post-war disenchantment overwhelmed the intellectual class, when glamour, sex and emotion dominated the film arts and magazines and glitz dominated Hollywood. When more famous social commentators like H.L. Mencken, Walter Lippman and Sinclair Lewis lampooned, decried and doubted the small town American intellect – the so-called “revolt from the village” – King celebrated what Mencken called the “booboisie.” Comics historians often characterize the post-1915 period of the medium as a kind of literal and figurative domestication. As newspaper syndication expanded into every burg, the mass media business of comics needed to shave the edges off of a once-raucous and urban-focused art form. Shifting the focus to family relations and suburbia, relying on more repartee than prankish violence, made the comic strip more acceptable to a mass audience.

Continue readingThe Rapidtoodleum Will Save Us All

In the New York World on April 5 1904, a giant but apparently friendly robotic beast vaulted from an unfinished New York City subway entrance to address some of the city’s most pressing concerns. Daily, and for the next week, this cartoon “Rapidtoodleum” offered rapid transit that solved for a much-delayed subway project, exposed gambling in Harlem, proposed an alternative to overpriced city housing, outpaced a newfangled automobile, and lampooned the florid fashion in women’s hats.

Continue readingWhen Superman Was Woke?

America needed a hero. That is how Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster remembered the late-1930s world in which their modern myth soared. Everyone is familiar with the Clark Kent origin story: orphaned by cosmic circumstance; rocketed to Earth; fostered by the Kents in the american breadbasket; super-powered by our planet’s physics; and taking on his secret identity as the milquetoast reporter. It is that rare mass mediated pop culture fiction that genuinely approaches folk mythology. It is an origin that compels retelling for every generation. Less attention has been paid to his political roots, however. Every comic strip in the adventure genre especially has an identifiable political slant, most obviously in its choices of wrongs to right and the villains to subdue. The famously conservative Chester Gould in Dick Tracy and populist Harold Gray in Little Orphan Annie were the most overt. Less obvious was the implicit imperialism of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and most of the adventure pulps, which characterized non-Western cultures as at best quaintly primitive or at worst inherently brutal.

Continue readingFlesh, Fantasy, Fetish: 1930s and the Return of the Repressed

The sheer horniness of the otherwise circumspect American newspaper comics in the 1930s is as unmistakable as it is overlooked in the usual histories. I have written about the kinkiness of 30s adventure in bits and pieces in the past. But rereading Dale Arden’s “obedience training” at the hands of the dominatrix “Witch Queen” in Flash Gordon, reminded me how much unbridled fetishism romped through the adventure comics of Depression America. Any honest history of the American comic strip really needs to have “the sex talk” about itself.

Continue reading