Chris Aruffo may not have planned to be a publisher, but somehow he managed to accomplish something that others couldn’t. In just a few years he published the full run of V.T. Hamlin’s Alley Oop dailies as well as Dave Graue’s run. More than that, he made the series affordable and used pristine source material for best possible rendering of this beautifully designed strip. Chris sat down with me recently to reflect on that experience. We discuss his history with Alley Oop, locating good sources, why this series comes in so many different dimensions, and can reprinting old comics make business sense? But with this interview we launch a series of interviews with reprint publishers where we brainstrom ways that 20th Century comic strips can be made relevant and inspiring to the next generations of comics fans and creators.

Continue readingTag Archives: 1930s

“Tycoons of Comedy”: Building the Myth of the Modern Cartoonist

“But the [comic] strip has suffered from mass production and humor hardening into formula…. It has sacrificed its original spirit for spurious realism.” – “The Funny Papers”, Fortune Magazine, April, 1933.

Who could say such a thing in 1933, just as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers, Tarzan and Terry were about to launch what many consider a “golden age” of American comic strips? But in a major feature in its April 1933 number, Fortune magazine lamented the new adventure trend as a sign of the medium’s decline. In their telling, comics were losing an antic, satirical edge that had distinguished them from the gentility of American literature or saccharine romance of silent film. In particular, the Fortune piece (unattributed so far as I could tell), bemoaned the rise of the dramatic “continuity” strip in place of gags. They single out Tarzan in particular as a corporate product that suffers from too many scribes and artists not working together. “The strip wanders through continents and cannibals with incredible incoherence,” they say. And to be fair, who could have foreseen in 1933 that Flash, Dick, Terry and Prince Val were about to redirect the “funnies” from hapless hubbies and bigfoot aesthetics towards hyper-masculinized heroism and a new realism that readers found far from “spurious?”

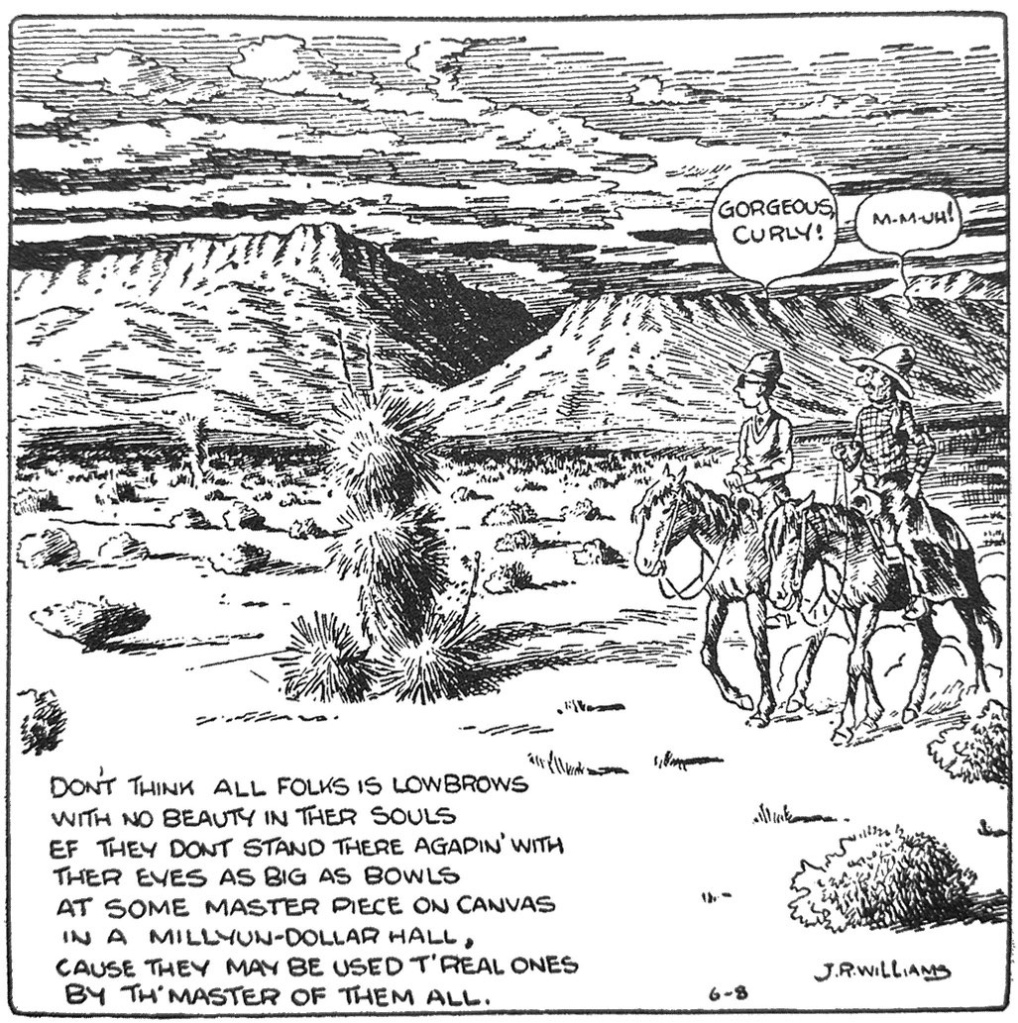

Continue readingCartooning the ‘American Scene’: Comics as Modern Landscape

We are such suckers for highbrow validation. Sure, we pop culture critics and comics historians talk a good game about bringing serious critical scrutiny to popular arts, our respect for the common culture…yadda, yadda. But our pants moisten whenever the intelligentsia deign to take our favorite arts seriously, or we find some occasional reference or connection between the “high” and “low” culture labels that we claim to disown. Comic strip histories love to gush over Cliff Sterrett’s appropriation of Cubist stylings in Polly and Her Pals. Although his dalliance with cartooning was brief, Lyonel Feininger’s Expressionist turn in the Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie loom so large in comics history you would think he was a beloved mainstay of the Sunday pages. In face, he was a fleeting presence. Picasso’s devotion to the Little Jimmy strip suggests somehow that Jimmy Swinnerton was onto something deeper than it seemed. And of course the critical embrace of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat started early, when Gilbert Seldes and e.e. Cummings, among others, primed us to believe the greatest of all comics for its surreal aesthetic and mythopoeic narrative.1 Never mind that the strip suffered limited distribution and perhaps narrower audience appeal. Indeed, an entire scholarly anthology, Comics and Modernism is a recent map of all the ways in which comics studies tries to wrap the “low” comic arts in the (to my mind) ill-fitting coat of high modernism.2

Continue readingWhen Superman Was Woke?

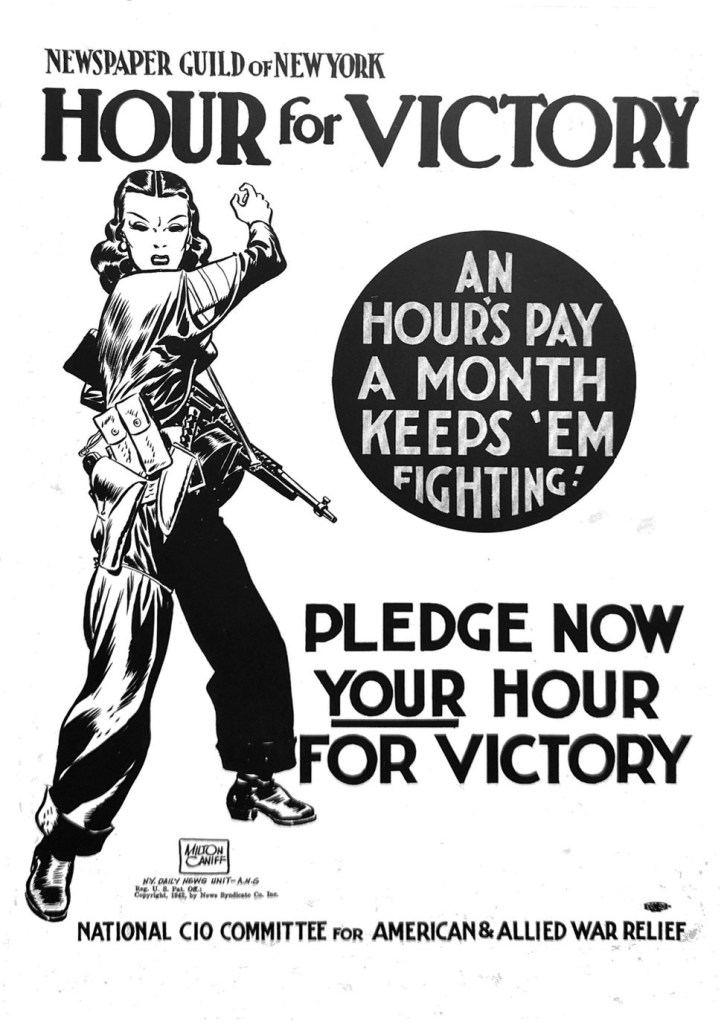

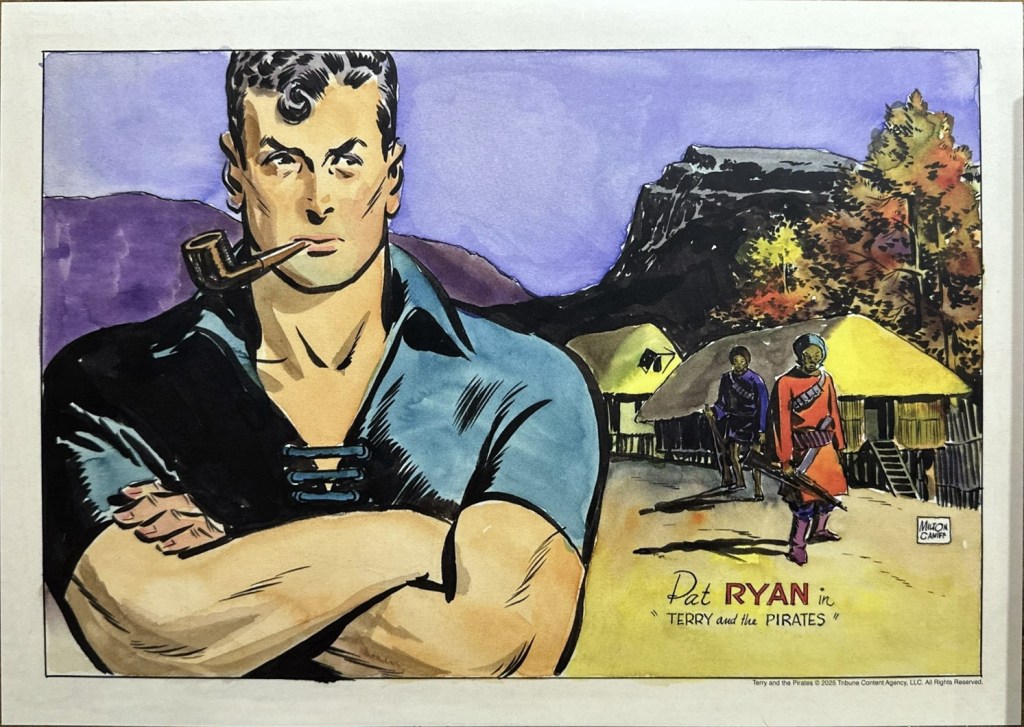

America needed a hero. That is how Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster remembered the late-1930s world in which their modern myth soared. Everyone is familiar with the Clark Kent origin story: orphaned by cosmic circumstance; rocketed to Earth; fostered by the Kents in the american breadbasket; super-powered by our planet’s physics; and taking on his secret identity as the milquetoast reporter. It is that rare mass mediated pop culture fiction that genuinely approaches folk mythology. It is an origin that compels retelling for every generation. Less attention has been paid to his political roots, however. Every comic strip in the adventure genre especially has an identifiable political slant, most obviously in its choices of wrongs to right and the villains to subdue. The famously conservative Chester Gould in Dick Tracy and populist Harold Gray in Little Orphan Annie were the most overt. Less obvious was the implicit imperialism of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and most of the adventure pulps, which characterized non-Western cultures as at best quaintly primitive or at worst inherently brutal.

Continue readingFlesh, Fantasy, Fetish: 1930s and the Return of the Repressed

The sheer horniness of the otherwise circumspect American newspaper comics in the 1930s is as unmistakable as it is overlooked in the usual histories. I have written about the kinkiness of 30s adventure in bits and pieces in the past. But rereading Dale Arden’s “obedience training” at the hands of the dominatrix “Witch Queen” in Flash Gordon, reminded me how much unbridled fetishism romped through the adventure comics of Depression America. Any honest history of the American comic strip really needs to have “the sex talk” about itself.

Continue readingThe Maturing of Milton Caniff

Milton Caniff’s landmark adventure Terry and the Pirates has been among the most reprinted newspaper strips of all time…and deservedly so. The artist’s fame for establishing the tone, cadence, composition and dramaturgy of the mid-century adventure genre in comics is well known. I won’t rehash it here. The latest and most ambitious reprint Terry project concluded this week when Clover Press and the Library of American Comics shipped the final three volumes in the 13 book Terry and the Pirates: The Master Collection. As I said in my initial review of the first volumes, the series is magnificent, if you don’t mind juggling oversized tomes. The sourcing of best available art, coloration and overall reproduction are the best I have seen among the many renderings of Terry over the years. This is LOAC’s second go at the strip. The imprint was launched two decades ago with a 6-volume oblong set. The first 12 volumes of the Master Collection reprint the full run from inception in 1934 through Caniff’s exit in 1946. A thirteenth volume carries new commentary, ancillary art and all of the front matter from the earlier series. Kudos to LOAC and Clover. Unlike many comic strip reprint projects that lumber for years, or peter out in mid-run, this one only took three years to complete. This final tranch of volumes also comes with a packed in bit of extra art (see above.

Continue readingTijuana Bibles: The Alternative America of Lust

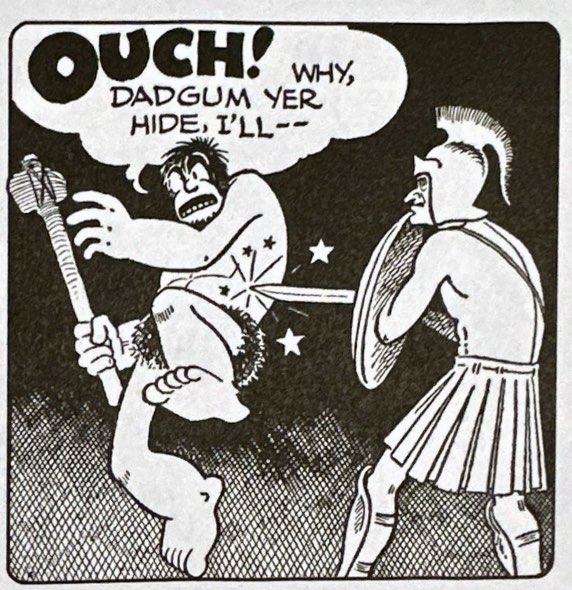

The underground sex comics of the Great Depression were not just an interesting sidebar to comics strip history. More than 700 of these 8-12 page titles were widely distributed in the 1930s through a clandestine, ramshackle shadow syndicate. The art was often at least as crude as the situations and banter. But their connection to mainstream comics were unmistakeable, mainly because they started by supplying Popeye, Moon Mullins, Blondie and Dagwood, Major Hoople, Betty Boop, and most major strip heroes with the raging libidos their real world creators left out. In their early years, the TBs depicted essentially the imagined sex lives of cartoon superstars. [FAIR WARNING: WHILE THE IMAGES TO FOLLOW HAVE BEEN CENSORED TO ABIDE BY WORDPRESS TERMS OF SERVICE, THE SITUATIONS AND LANGUAGE EVEN IN THESE CENSORED COMICS ARE VULGAR, MISOGYNIST, RACIST AND OFFENSIVE TO ALMOST EVERY CONTEMPORARY SENSIBILITY, AND MOST OF THOSE OF THAT TIME. IT WAS INTENTIONAL. TRANSGRESSION WAS THE POINT]

Continue reading