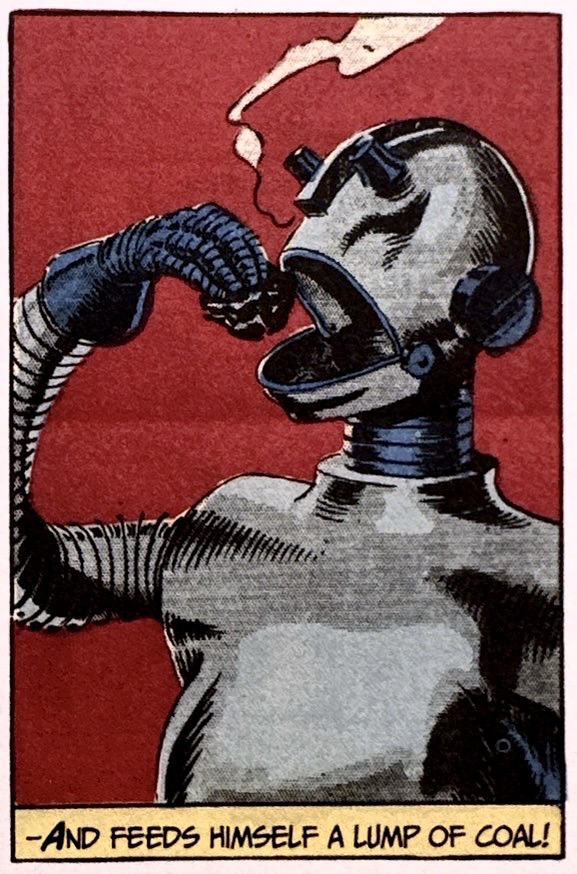

Here is your Weekly Weird. Call it comfort food for robots. When Lee Falk and Phil Davis sent their Mandrake the Magician into “Dimension X” in 1937 they found early stage AI. Metal Men were made of conscious “living metal” that dined on coal and oil and enslaved humans. This was a remarkable episode with loads of compellng art and wildly imaged alternative physics. We went into it in depth here.

Tag Archives: adventure strips

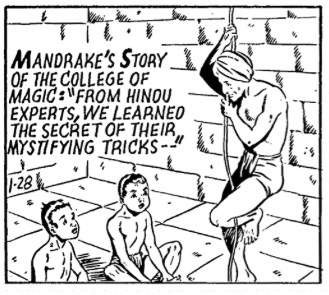

Baby Mandrake’s Evil Twin?

Lee Falk’s tux-clad adventure hero Mandrake the Magician was among the strangest characters on the comic page since his mid-30s launch. As we have covered here before, some of his strips were downright surreal. And so you just know that his origin story must be wild. According to a 1949 flashback sequence, orphaned twins Mandrake and Derek are raised by an island school of monk-like magicians. The boys learn ancient mystic secrets like “Instant Hypnosis, the art of making things appear to be what really aren’t — the art of the seemingly impossible.” But Derek shows his evil nature early and resurfaces in a 1949 story that threatens Mandrake’s reputation. Dig the signature slicked back hair on those toddler tops.

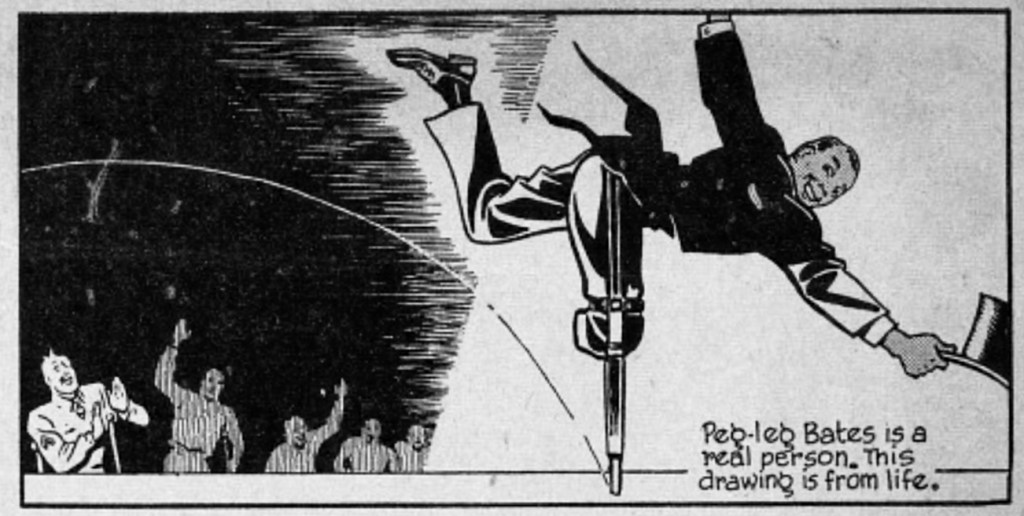

Peg-Leg Bates Gets a Cameo in Hank

The Weekly Weird. Coulton Waugh’s experimental adventure hero Hank was the first disabled character to lead a comic strip. Shortly after losing his leg, the veteran Hank finds inspiration from real-life Broadway sensation, Peg-Leg Bates. Bates was a sensation on the stage show circuit around the country during the 30s and 40s on Broadway. The sharecropper’s son lost his leg in a cotton gun accident at the age of 12. He was determined to overcomethe disability and eventually turned it into a dance routine. More on Hank and Bates here.

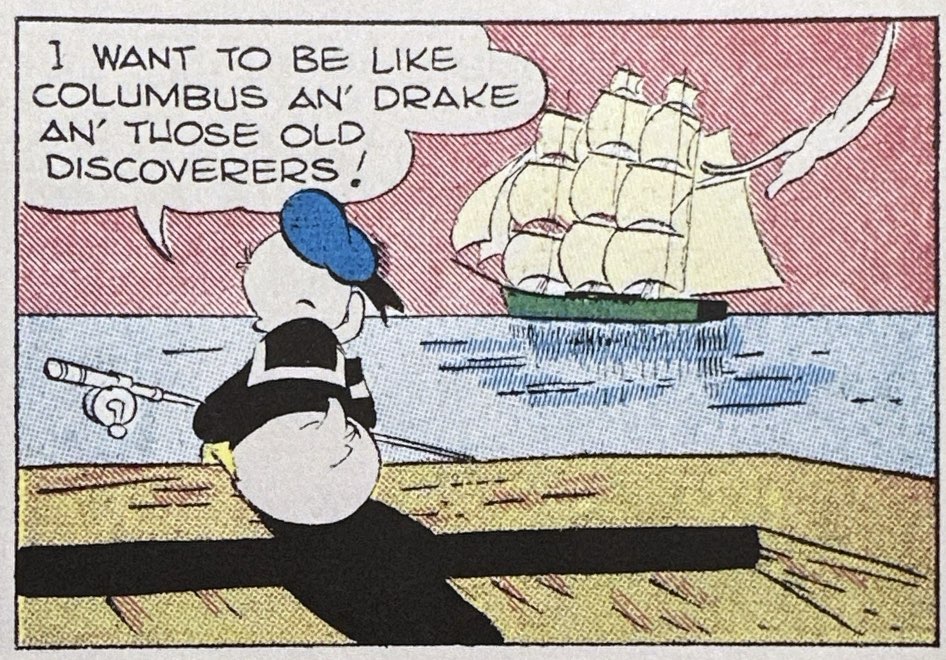

A Bigger Barks: Taschen Supersizes the Duck Man

Is a bigger Barks a better Barks? Taschen’s long-awaited Disney Comics Library: Carl Barks’s Donald Duck. Vol. 1. 1942–1950 supersizes the Duck Man, and we are all the richer for it. This is one of their “XXL” volumes, so let’s go to the tape. It weighs in, literally, at 11+ pounds: over 626 11 x 15.5-inch pages that include the longer Donald Duck stories from 15 issues of Western Publishing’s Four-Color series. up to 1950. These include some of the greatest expressions of Barks’s quick mastery of the comic book format. In “The Old Castle’s Secret” (1948) he uses page structure, atmospherics and pace to create real suspense. His masterpiece of hallucinogenic imagination married to landscape precision surely is “Lost in the Andes” (1949). And his well-tuned sense of character is clear in creating a purely American icon of endearing greed in Uncle Scrooge in “Christmas on Bear Mountain” (1947). Of course we have seen these and many of the other stories in this collection reprinted before. So, to answer my own question, does scaling up Barks give us a better Barks?

Continue reading

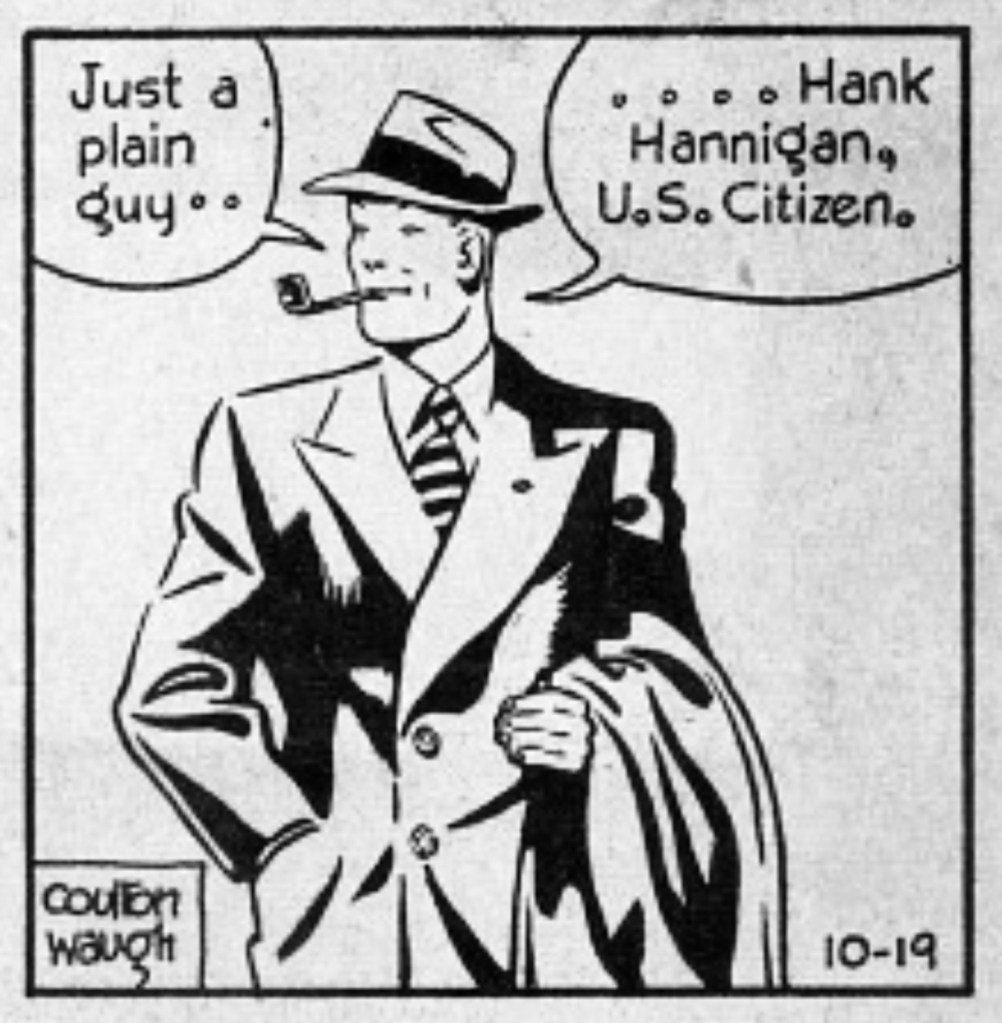

Recovering Hank: America’s Anti-Fascist Hero

A WWII veteran amputee who doesn’t want to journey (or save) the world. Just a grease monkey who yearns to get back to the garage, marry his sweetheart, and figure out what he and his pals’ great sacrifice really meant. That was Hank Hannigan, the titular, unlikely hero of the short-lived 1945 comic strip Hank, which creator Coulton Waugh conceived as an answer to traditional adventures. “To get a new character I go into the subways and actually draw them,” he told Editor and Publisher before Hank’s April launch. “I want the people of America to stream into the strip.”

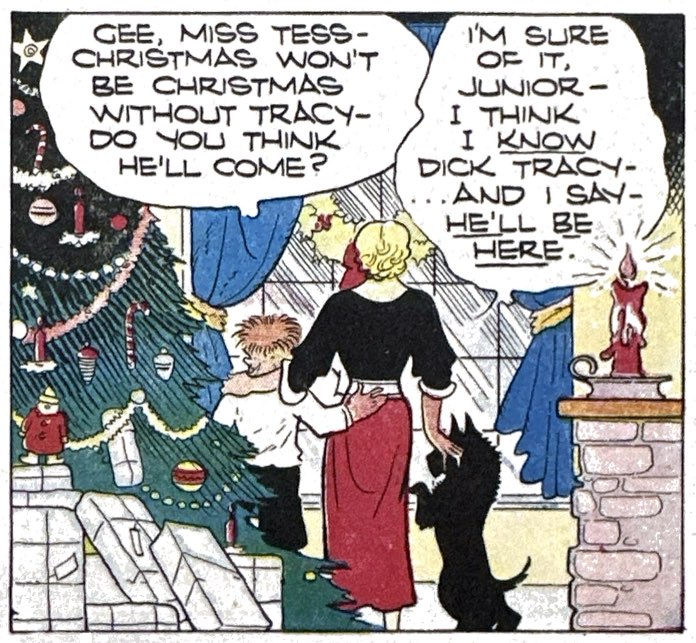

Continue readingA Merry Dick Tracy Christmas

Christmas always had a special place on the comic strip page. Many artists creatively wove Yuletide celebrations into their storyline or just broke the fourth wall for a day to send holiday messages directly to readers. Over the next few days we will recall some of the most creative examples. But let’s start with one of the heartiest celebrants of the holidays, Dick Tracy, and trace how he and Chester Gould treated the holiday.

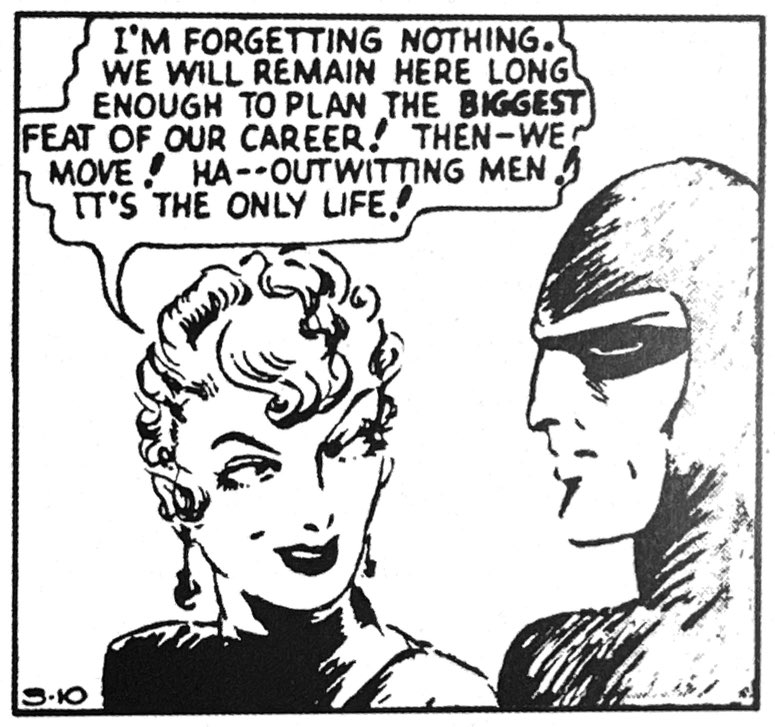

Continue readingGal Gangs, Femdoms and Queen Bees: Matriarchal Mayhem in the 1930s

Women-led “Amazon” worlds popped up in a ranges of comic strips during the 1930s and 40s, and they voiced a range of ideas about the prospects for matriarchal rule. In an earlier article we explored otherworldy femtopias in Buck Rogers 25th Century, the Connie strip’s vision of the 30th Century and even in the “Bone Age” of caveman Alley Oop. More muscular he-men heroes like The Phantom and Tarzan, however, found the prospect of matriarchy a bit more, well, shall we say, threatening?

Continue reading