Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy has been among the most reprinted strips of all time. The reasons are obvious, and I don’t need to rehash this site’s exegesis on my personal favorite. Tracy was the strip that turned me on to classic newspaper comics. Gould’s singular visual signature, his grisly violence, grotesque villains and deadpan hero made Dick Tracy compelling on so many levels. And now we get yet another packaging style from the same Library of American Comics group that finished its magisterial 29-volume complete Gould run, 1931-77. With new publishing partner Clover Press, LOAC has reworked some of its earliest projects, like the magnificent upgrade of Terry and the Pirates and the first six volumes of The Complete Dick Tracy. And now we get slipcased, paperback editions of prime-time Gould, 1941 through 1944. Much more affordable, manageable, and available than the original LOAC volumes, each of which covered about two years of comics, the four $29.99 books are also available as a discounted set from Clover. This new series started as a crowd-funded BackerKit project last year.

Continue readingTag Archives: Dick Tracy

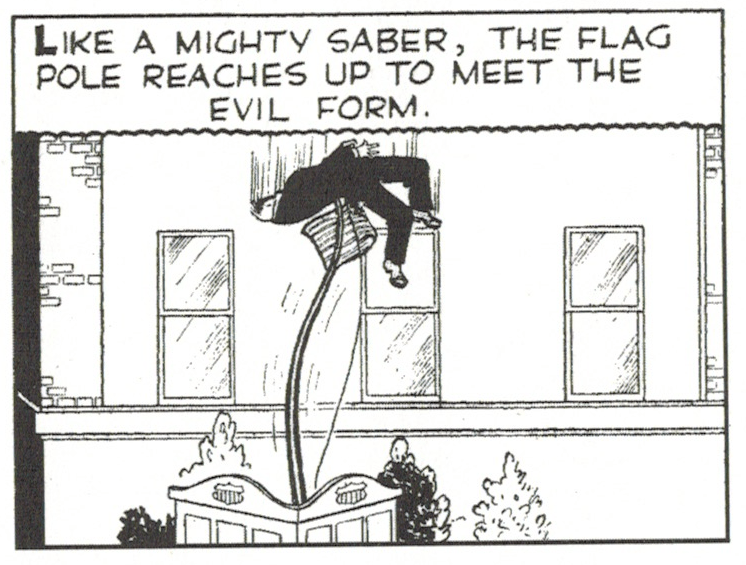

The Impaling of The Brow

Yeah, that’s gonna leave a mark. Impaled on an American flagpole, sadistic WWII spy and Dick Tracy villain The Brow gets poked by poetic justice. More grisly villain deaths from Tracy creator Chester Gould here.

Gould’s Dick Tracy is my lifetime favorite strip, which I have already recounted in our About Panels and Prose section. I have covered Dick Tracy from many angles since starting this site years ago. You can find pieces on Flattop, Flattop Jr. the arch conservatism of Gould and his here, as well as assorted short takes on Tracy here.

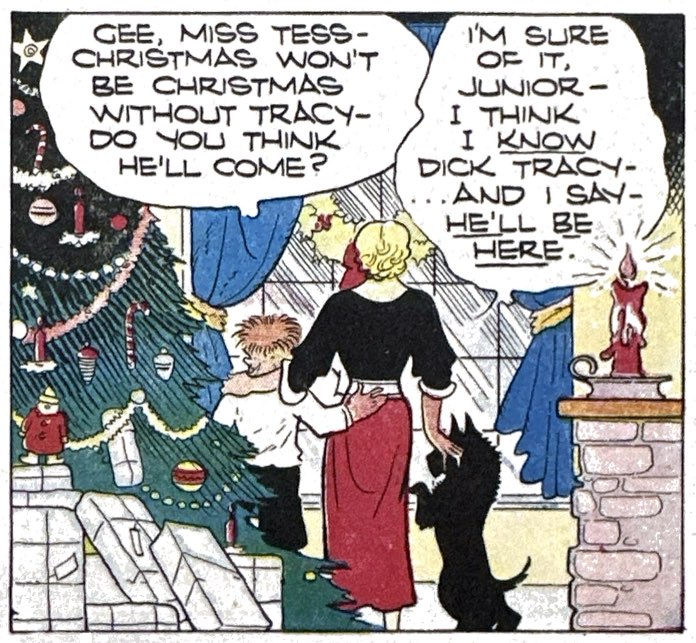

A Merry Dick Tracy Christmas

Christmas always had a special place on the comic strip page. Many artists creatively wove Yuletide celebrations into their storyline or just broke the fourth wall for a day to send holiday messages directly to readers. Over the next few days we will recall some of the most creative examples. But let’s start with one of the heartiest celebrants of the holidays, Dick Tracy, and trace how he and Chester Gould treated the holiday.

Continue readingJust In: LOAC’s Updated Dick Tracy Editions

A lot of comic strip fans have been looking forward to these updated early volumes of The Complete Dick Tracy. Here are Vols. 1 and 2, just in today. This project reprints the first six volumes in the larger format that matches the rest of the series.

Continue readingJunior Marries Moon Maid

By the end of his career in 1977, Dick Tracy creator Chester Gould was notoriously reactionary. His disdain for the counter-cultural forces at play in the 1960s and 70s, for liberal explanations of criminal behavior, were clear in the strip itself. In fact, his resistance to leniency in America’s legal system, and progressivism in general, had been baked into his epic since its roots n the gangster era of 1931. From the start, Dick Tray was an exploration of individual valor and evil rather than institutional or social forces. Gould’s take on the 50s moral panic around “juvenile delinquency” via Flattop Jr. is an excellent example. And the moral universe of Dick Tracy hinged on the personal evil of villains(usually embodied in physical abnormalities) and the poetic symmetry of their deaths via some kind of retributive justice.

Continue readingDick Tracy Battles The JDs: Flattop Jr. and Joe Period

Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy was created in the 1930s as a response to the romanticization of gangsters and declining respect for law enforcement. And throughout its run under the notoriously conservative artist made no secret of his disdain for many modern trends. In the 1950s when mania around “juvenile delinquency” dominated popular culture, Gould added to his famous rogues gallery a few of these teen terrorists. Most notable for its outright weirdness (even for Gould) are the 1956 episodes spanning Joe Period and Flattop, Jr., the son of one of Tracy’s most famous nemeses of the prior decade.

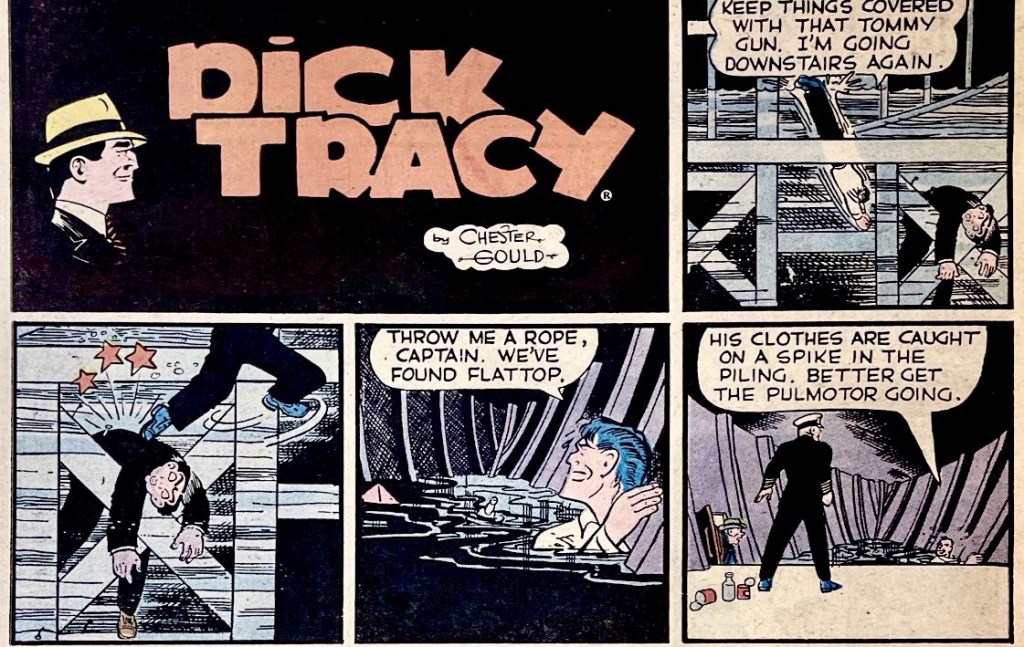

Continue readingThe Death of Flattop (1944)

Feels like peak Gould. This May 1944 Sunday shows off Gould’s visual sense of place, love of clean geometry and perspective, retributive Justice.