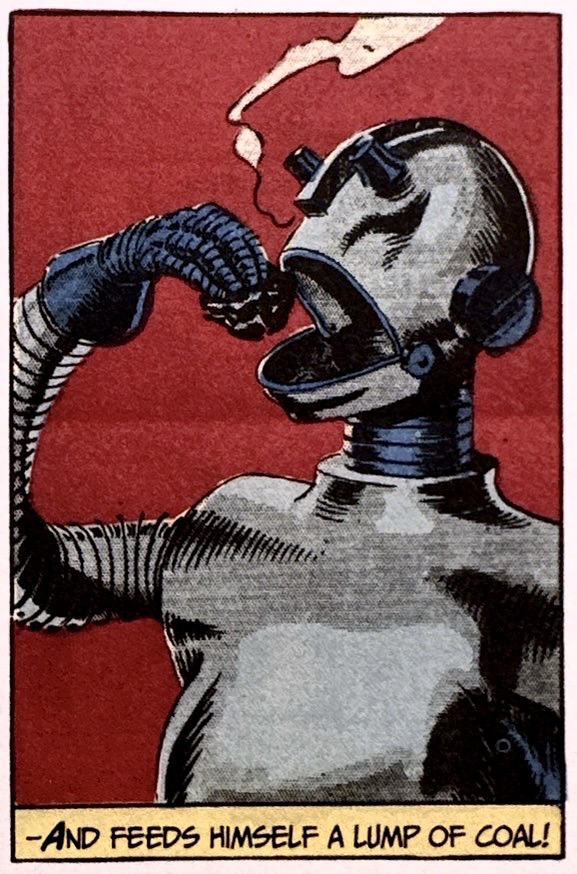

Here is your Weekly Weird. Call it comfort food for robots. When Lee Falk and Phil Davis sent their Mandrake the Magician into “Dimension X” in 1937 they found early stage AI. Metal Men were made of conscious “living metal” that dined on coal and oil and enslaved humans. This was a remarkable episode with loads of compellng art and wildly imaged alternative physics. We went into it in depth here.

Tag Archives: 1930s

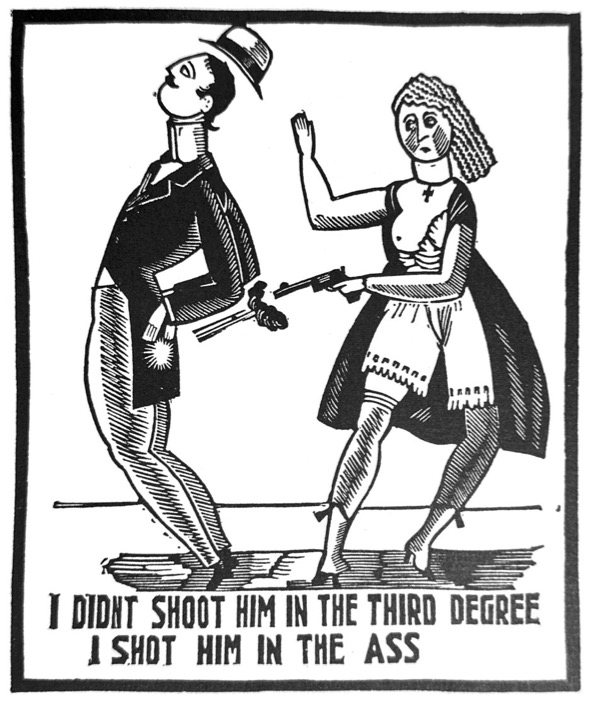

“I Shot Him In the Ass!” John Held Jr.’s Lewd Linocuts

John Held Jr.’s highly stylized, fine line cartoons are identified with “The Jazz Age” of Fitzgerald’s 1920s for good reason. His imagery on the covers of Fitzgerald books, in his Oh, Margy and Merely Margy comic strips and especially in his work for the early New Yorker and other humor magazines pretty much defined that decade visually. He found a way toi make privileged youth look even more air-headed and frivolous than they prbably were. It made him enormously wealthy, for a time, and in constant demand. Yet, for all of his identification with modernity, Held was deeply nostalgic. Many of his other illustrated works departed radically from his signature flapper stylings and used instead a pre-modern linocut technique that gouged an image into a linoleum surface to effect a primitive woodcut-like effect. Rob Stolzer recently posted the full run of Held’s Civilization’s Progress series from Liberty magazine (1931-32), where Held contrasted the Gay Nineties with contemporary life by juxtaposin his flapper and linocut styles.

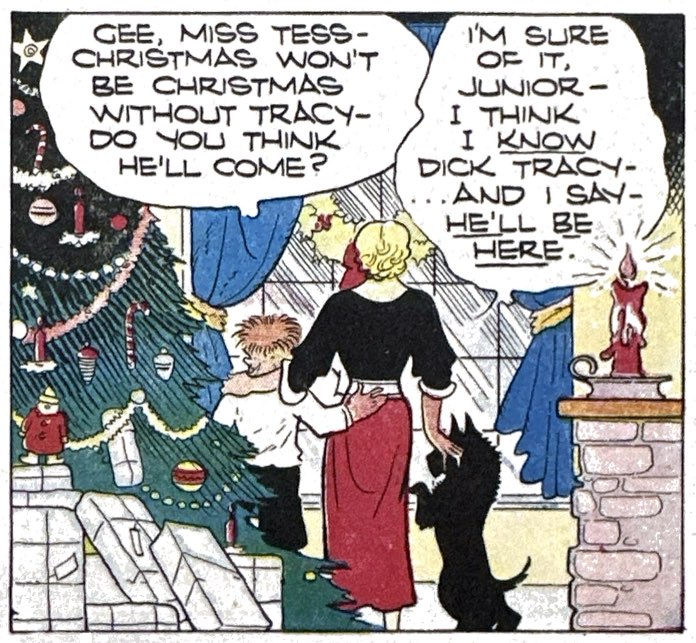

Continue readingA Merry Dick Tracy Christmas

Christmas always had a special place on the comic strip page. Many artists creatively wove Yuletide celebrations into their storyline or just broke the fourth wall for a day to send holiday messages directly to readers. Over the next few days we will recall some of the most creative examples. But let’s start with one of the heartiest celebrants of the holidays, Dick Tracy, and trace how he and Chester Gould treated the holiday.

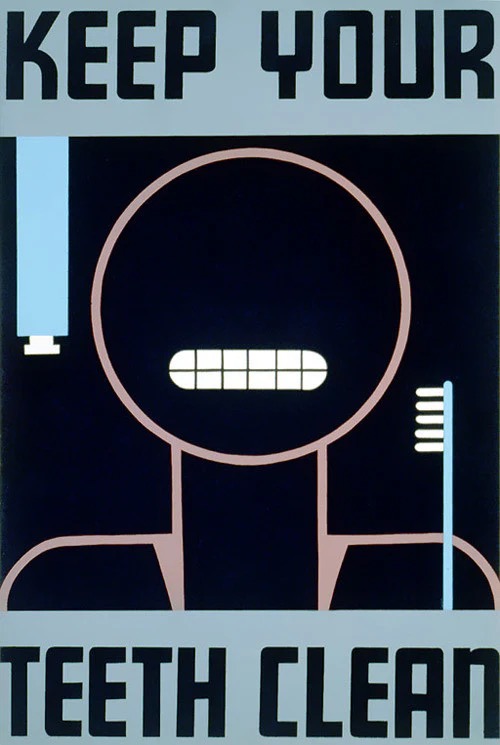

Continue readingShelf Scan 2025: That Modern Look

Two of my favorite books this year were not about comics specifically but about the larger visual culture in which comics emerged during the first half of the American 20th Century. Christopher Long’s overview of commercial graphic ideas, Modern Americanness: The New Graphic Design in the United States 1890–1940 takes us from the poster art craze of the 1890s to the streamlining motif that flourished in late 1930s graphic storytelling. And Ennis Carter’s Posters for the People: Art of the WPA reproduces nearly 500 of the best posters from the New Deal-funded Federal Art Project of the 1930s. Between the two books we peer into a comics-adjacent history of commercial art and how it was incorporating design ideas that expressed the experience of modernity and absorbed some of the artistic concepts of formal modernist art. Although neither book mentions cartooning per se, their subjects are engaged in the same cultural project as cartoonists – to find visual languages that capture and often assuage the dislocations of modern change.

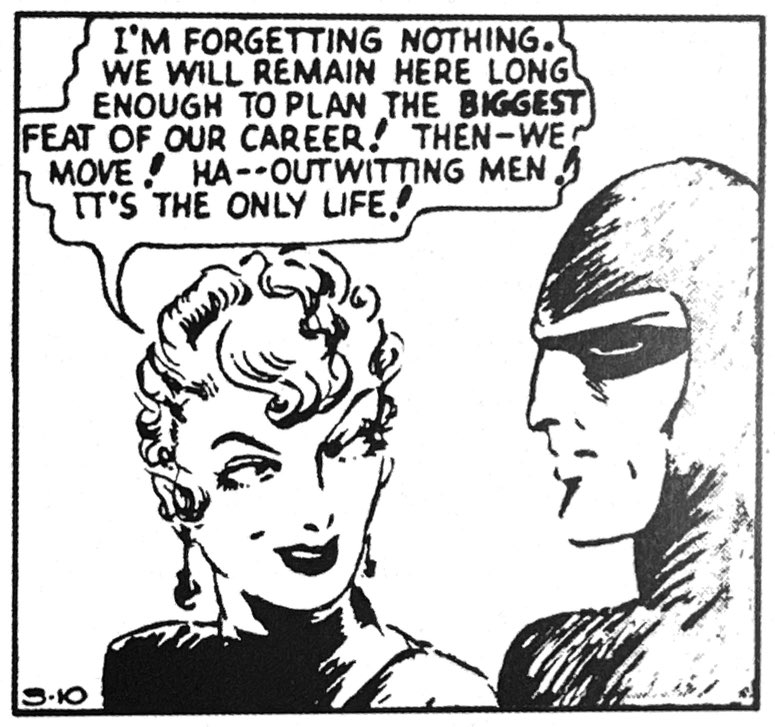

Continue readingGal Gangs, Femdoms and Queen Bees: Matriarchal Mayhem in the 1930s

Women-led “Amazon” worlds popped up in a ranges of comic strips during the 1930s and 40s, and they voiced a range of ideas about the prospects for matriarchal rule. In an earlier article we explored otherworldy femtopias in Buck Rogers 25th Century, the Connie strip’s vision of the 30th Century and even in the “Bone Age” of caveman Alley Oop. More muscular he-men heroes like The Phantom and Tarzan, however, found the prospect of matriarchy a bit more, well, shall we say, threatening?

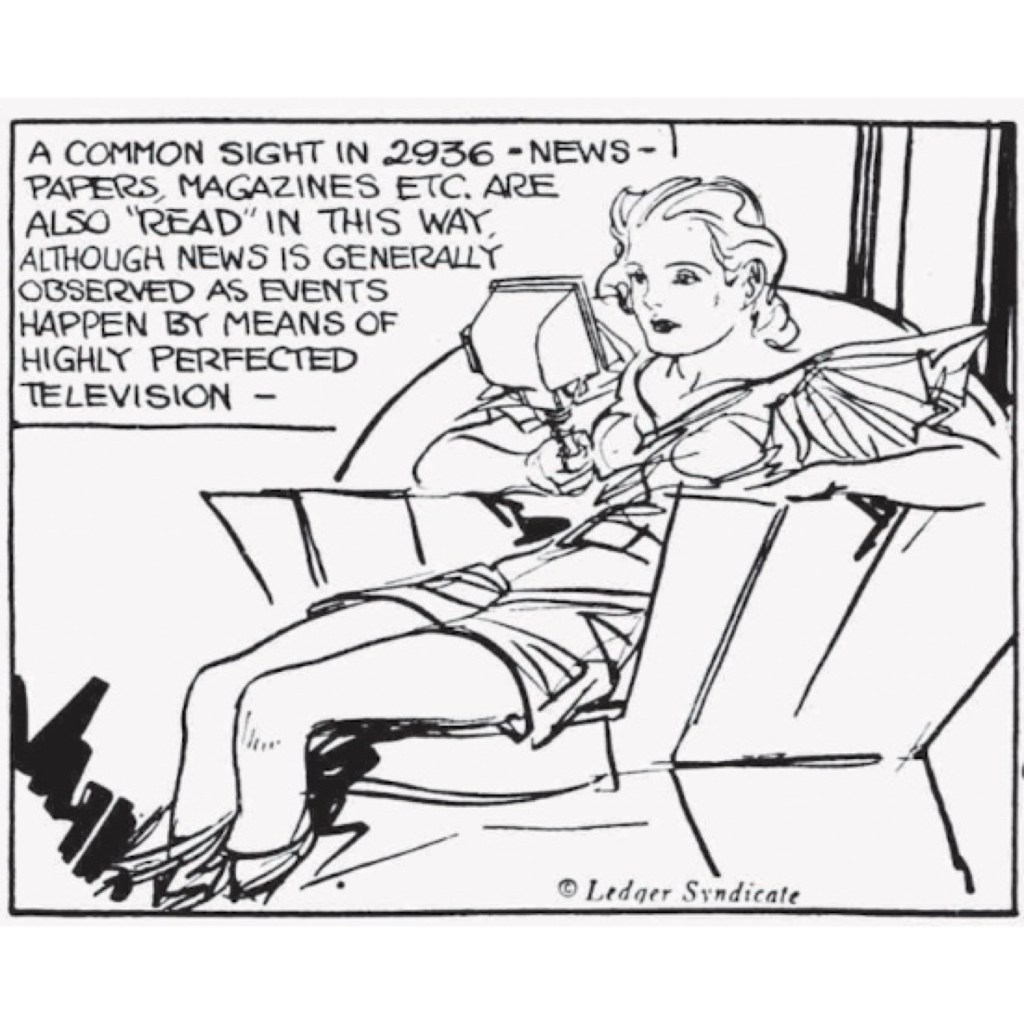

Continue readingYour 2936 Model iPad…Via 1936

When Frank Godwin sent his adventure comic strip heroine Connie Kurridge a thousand yeas into the future, this amateur engineer had a field day imagining technologies of the next millennium. During the extended story arc, the Connie strip ran a “topper” on the bottom each week called Wonder Land. The content was often hosted by the “Dr. Chrono” character from the main storyline who had invented the time travel machine. the strip served as a kind of explainer series that elaborated on technical details related to that week’s tech of the future. But one week we get a particularly prescient future gadget that resembles the best steampunk visions from Buck Rogers.

Continue readingAmazon Dreams: Defending The Matriarchy in Depression Era Comics

“A hundred yard jump! And a girl soldier, too! Say, sister, need help?

The first thing Buck Rogers sees when he wakes from his 500 year slumber is a flying bare-legged woman…with a gun. That Jan. 7, 1929 strip launched American newspaper comics into a new age of heroic continuity strips, which historians have dubbed “The Adventurous Decade.”1 And across Buck, Flash (Gordon), Dick (Tracy), Pat (Ryan), the Prince (Valiant) and of course Tarzan, this decade in the newspaper back pages became famous for a pulpy hyper-masculinity that culminated in the rise of the superhero in the late 30s. And yet, as Buck’s premiere strip suggests, it would also be one of the weirdest stretches in the depiction of powerful women in popular culture. This would play out especially in adventure comics’ curious fixation with putting women in charge during the Depression years. Amazon tribes, criminal gal gangs, and futuristic matriarchies peppered adventure strips. We are all familiar with the creation of Wonder Woman in 1941 and her origin on the ladies-only Paradise Island.2 But this trope started in comics more than a decade earlier, first with Buck but then resurfacing in The Phantom, Tarzan, Alley Oop, and Frank Godwin’s Connie. Fantasizing about matriarchal societies within the adventure genre was not just a clever escapist plot device. Each of these Amazon worlds imagined different alternative societies where women called the shots and shaped the culture. Taken as a while, this pop culture trope suggested a deep ambivalence about the changing roles and independence of women. Putting women in charge was a kind of gender lab that played with ideas of feminine power under the stress of both Depression and modernization.