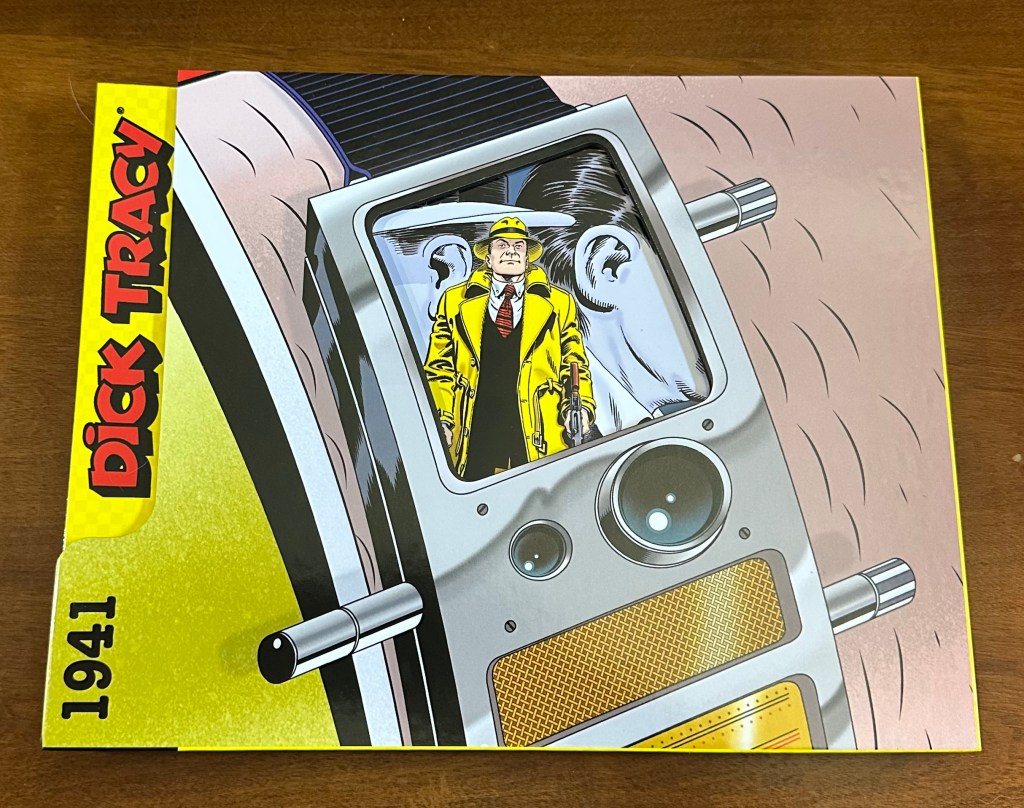

Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy has been among the most reprinted strips of all time. The reasons are obvious, and I don’t need to rehash this site’s exegesis on my personal favorite. Tracy was the strip that turned me on to classic newspaper comics. Gould’s singular visual signature, his grisly violence, grotesque villains and deadpan hero made Dick Tracy compelling on so many levels. And now we get yet another packaging style from the same Library of American Comics group that finished its magisterial 29-volume complete Gould run, 1931-77. With new publishing partner Clover Press, LOAC has reworked some of its earliest projects, like the magnificent upgrade of Terry and the Pirates and the first six volumes of The Complete Dick Tracy. And now we get slipcased, paperback editions of prime-time Gould, 1941 through 1944. Much more affordable, manageable, and available than the original LOAC volumes, each of which covered about two years of comics, the four $29.99 books are also available as a discounted set from Clover. This new series started as a crowd-funded BackerKit project last year.

Continue readingTag Archives: writing

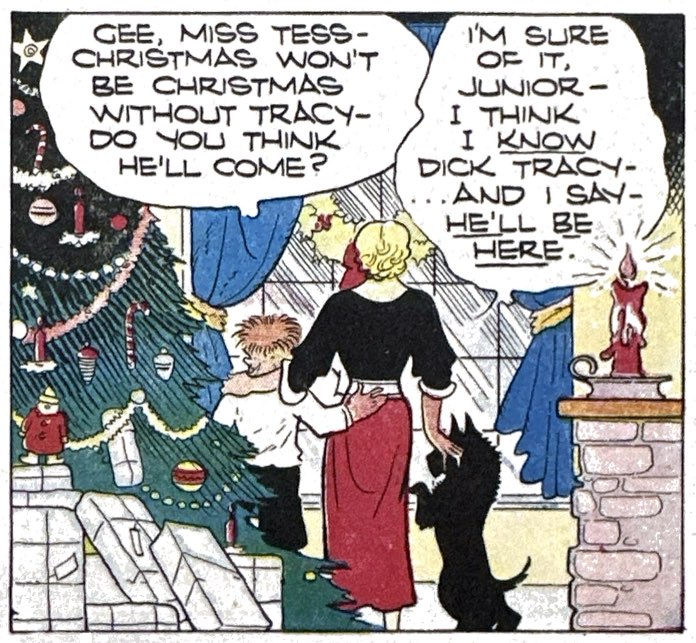

A Merry Dick Tracy Christmas

Christmas always had a special place on the comic strip page. Many artists creatively wove Yuletide celebrations into their storyline or just broke the fourth wall for a day to send holiday messages directly to readers. Over the next few days we will recall some of the most creative examples. But let’s start with one of the heartiest celebrants of the holidays, Dick Tracy, and trace how he and Chester Gould treated the holiday.

Continue readingGet Me to The Church on Time: Decoding the Postwar Cartoon Marriage Boom

“It is a old comical strip trick – pretendin’ th’ hero gotta git married.” It keeps “stupid readers excited,” Li’l Abner claims in 1952. Days later he unwittingly weds Daisy Mae, ending a nearly 20 year tease. But this time it was no “comical strip” trick. In fact, several perennial bachelors of the comics pages fell in a post-WWII rush to the altar. Along with Abner, Prince Valiant, Buz Sawyer, Dick Tracy and Kerry Drake all enjoyed funny page weddings between 1946 and 1957. Comic strip heroes were just following the lead of the real-world heroes returning from WWII. Desperate to make up for lost time and return to normality, over 16 million Americans got hitched in 1946, the year after war ended in Europe and the Pacific. But each of these strips framed the new normal in American life differently. As the best of popular art often does, Vale, Dick, Abner, Buz, Kerry and their mates offered Americans a range of stories, myths really, about what this new normal meant.

Continue readingDoes This Zeitgeist Make Me Look Fat?: An Overdue Appreciation of “Cathy”

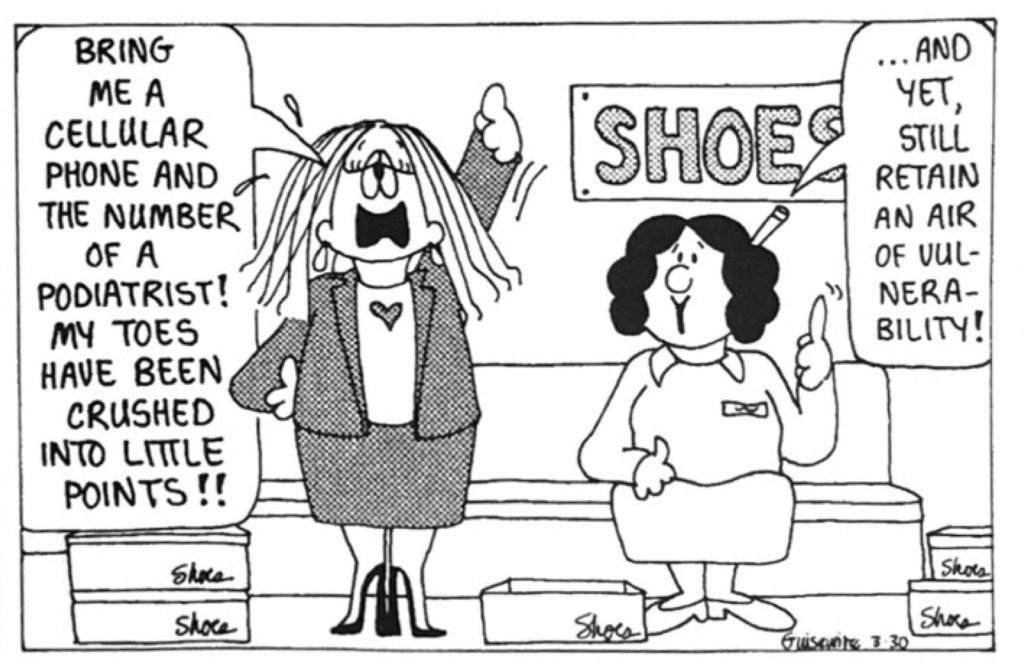

Across five decades of adulthood, every woman I have ever known was familiar, often intimately, with Cathy Guisewite’s Cathy (1976-2010). Our heroine’s struggles with new and old gender roles, the pressures of fashion and body messaging, diet trends, new tech, workplace culture…and MOM, always MOM, found their way into more diaries, onto more refrigerators and clipped into mother/daughter exchanges than any comic of its day. Tis a pity that so many of us male comics readers passed it over as “not for us” or simply unfunny. Spending a couple of days immersed in the new and most welcome 4-volume Cathy 50th Anniversary Collection ($225, Andrews McMeel) makes clear that Cathy was among the most insightful, witty and intelligent strips we had about the experience of post-counter-culture America. And I could have avoided a lot of stupid missteps with the women in my life if I had paid even glancing attention to Guisewite’s wisdom.

Continue readingOur Snooty Neighbors: When The Smythes Moved In

If you let the original art designer of The New Yorker loose on the Sunday comics page, then Rea Irvin’s The Smythes is pretty much what you would expect to get. For six years in the early 1930s, Irvin rendered the foibles and class anxiety of upper-middle class ex-urbanites Margie and John Smythe with impeccable Art Deco taste and reserve. Could we get anything less from the creator of Eustace Tilley, the monocled, effete and outdated New Yorker magazine mascot who appeared as the inaugural cover in 1925? Irvin was also responsible for the design motifs and even the typeface (“NY Irvin”) still in use at the fabled weekly. And The Smythes newspaper strip carried much of that magazine’s class ambivalence and self-consciousness, its droll observational humor, as well as its lack of real satirical edge. The Sunday feature ran in The New York Herald Tribune from June 15, 1930 to Oct. 25, 1936. It was among the most strikingly designed and colored pages in any Sunday supplement, even if its humor may have been too dry for most readers. Beyond the Trib, The Smythes only ran in about half a dozen major metros.

Continue reading

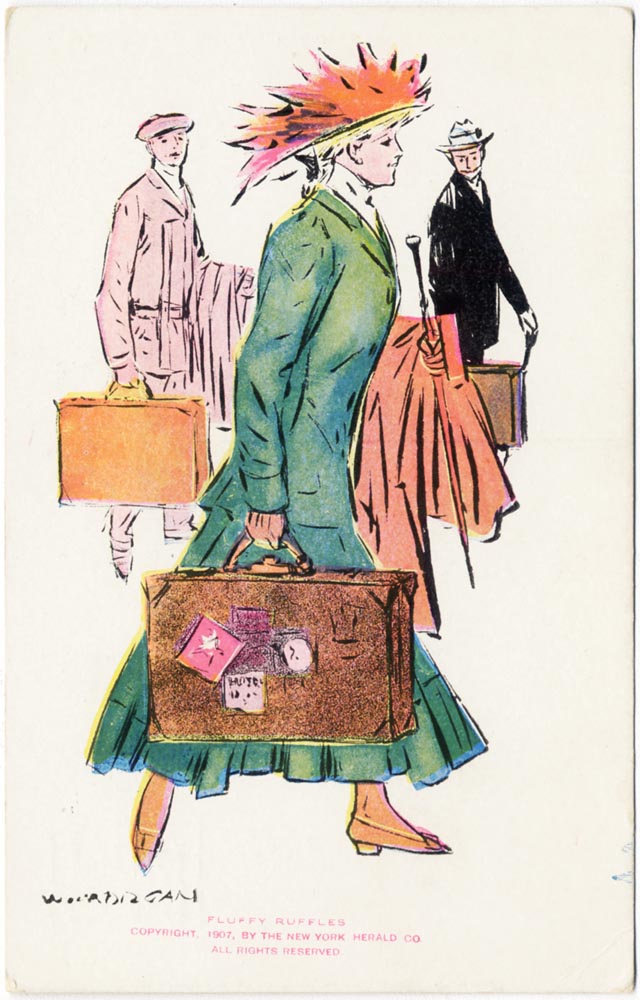

“Who Is Fluffy Ruffles?”: The Forgotten Cartoon Feminist of 1907

“Bah, for Mr. Charles Dana Gibson,” declared the Spokane Press in early 1908. Who needs the signature Gibson Girl anymore. “Miss Fluffy Ruffles is the newest type to which all the girls aspire.”1 The job-hunting, resourceful, and decidedly independent heroine became a national sensation shortly after her Feb. 3 premiere in the New York Herald. Fluffy was a pioneering woman in the workplace battling a reversal in fortune by making weekly tries as a journalist, florist, schoolteacher, dairy maid, waitress and more. The full page Sunday story was conceived and told in comic verse by a professional woman of note herself, the children’s and mystery writer Carolyn Wells. Herald illustrator Wallace Morgan dramatized the tale in vignettes that seemed to channel Charles Dana Gibson’s genteel magazine style. The series ran until early 1909 and quickly a multimedia juggernaut. The early episodes of her job-seeking stage were reprinted in book form before 1907 ended. Within six months of the launch The Herald started contests to find real-life Fluffy Ruffles that migrated to partner newspapers around the country. Paper dolls, chocolates, sheet music, branded hats and suits, even cigars, soon carried the Fluffy Ruffles brand. A 1908 Broadway musical production would travel the country until at least 1910, a year after the strip itself had ended.

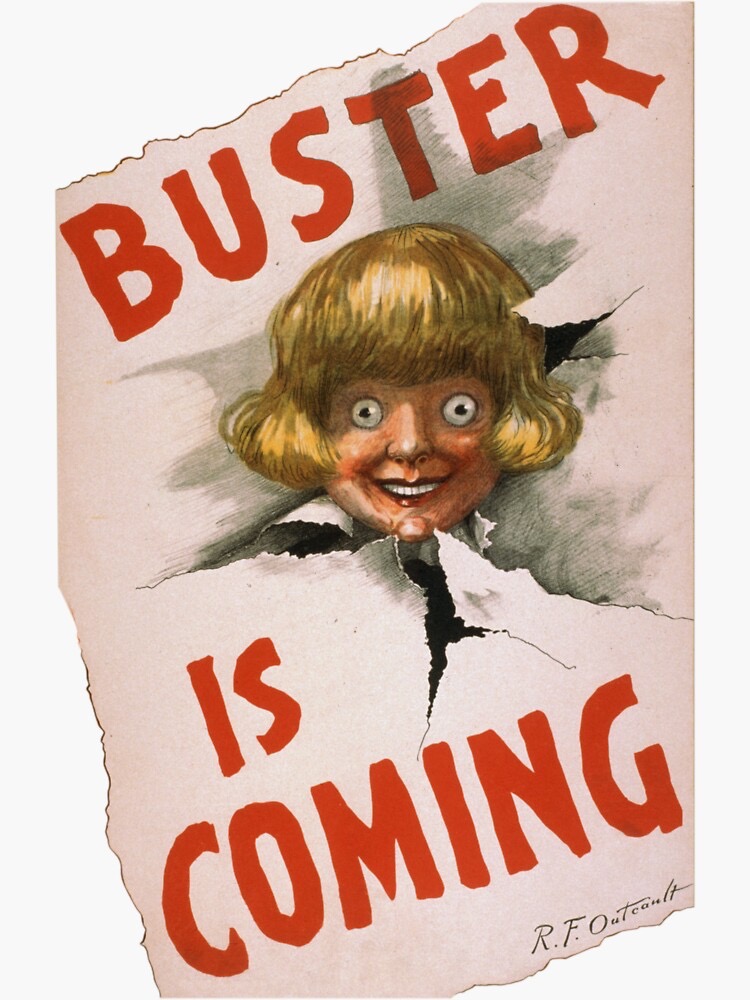

The Great Buster Brown ‘Scheme’ of 1906: Inventing Celebrity Endorsement

A 43-year-old man, something over 3 feet tall, is dressed in the signature, foppish, Buster Brown garb and wig. He commands his trained dog Tige to do tricks and then engages an audience of schoolchildren, sometimes hundreds, and prompts their pledge only to wear Buster Brown shoes. It was a good pitch in 1906. For local shoe merchants who secured this road show from the Brown shoe Company, “the scheme is the best they ever tried,” reported the trade publication Profitable Advertiser. This was the dawn of mass media celebrity endorsements and syndicated point-of-sale marketing programs.

By the time creator R.F. Outcault started licensing his spectacular Buster Brown comic strip character in 1904, its boyish pranks and domestic chaos were familiar to audiences across the nation. Soon after premiering on May 4, 1902 in The New York Herald, the strip became a national sensation. At first blush, Buster seems an unlikely brand ambassador. Along with the Katzenjammer Kids and the many other copy cat pranksters of the “Sunday Supplements,” he was a quintessential comics “smart boy,” just more obviously middle class. His were the kind of antics that were commonly denounced by social reformers, clergy and teachers’ associations for their cruel pranks and disrespect for authority. And yet, here he was, his weekly sins somehow whitewashed by commodification. When Outcault sold licensing rights to the Brown Shoe Company in 1904, and launched the partnership at the St. Louis World’s Fair that year, he was also contracting Buster out to another 200 brands.

But it was the Brown Shoe Company that elevated the Buster Brown partnership into one of the longest-running comic character associations in history. And this was among the first examples of an emerging mass media ecosystem driving a new consumer culture of mass consumption. Brown not only married a celebrity to a mass produced and distributed product, but it showed how to standardize and syndicate a marketing program to a new nationwide market. Along the way, the Buster Brown marketing program pioneered marketing directly to kids in order to influence their parents’ buying habits.

Dubbed “Reception Tours,” the model provided for a Buster actor and a Tighe for day-long visitation to the retail outlet to drum up attention and drive shoe sales for the shoes. According to the St. Louis government’s history site, the Brown company hired up to 20 “midget” actors and trained dogs to staff the many road shows, which ran until 1930. But a forgotten article, “Buster Brown, Advertiser” in the obscure trade paper Profitable Advertiser gives us a more detailed look at “how the scheme is worked.” Retailers who agreed to buy at least 50 dozen pairs of Buster Brown shoes could access the program from Brown. The company provided a package that included the talent as well as marketing templates for local newspaper ads and handbills which the retailer agreed to buy in support of the Reception.

In this 1906 iteration, the company hired a 3-foot tall, 43-year old former salesman and “orator of ability,” Major Ray. In a trip to the town of Berwick, Buster and Tighe enjoyed a full day touring the local sites and manufacturing plants, visiting local officials and leading a parade through town. These tours became wildly popular local events. A Brown salesman claimed that “There were in the neighborhood of 8,000 to 10,000 people out to witness the reception.”

But Buster and Tighe kept their aim at the sales job. As Profitable Advertiser describes it, organizers scheduled the parade to pass local schools around dismissal time. Kids would gather back at the shoe store (or even rented theaters) to watch Tighe perform tricks and Buster entertain and pitch the crowd. They stood before a 30-foot banner across the store window declaring “Buy Buster Brown Shoes for boys and girls here. Every pair the best.” At times the crowd of youngsters were asked to raise their hands to acknowledge they will wear only Buster Brown shoes.

The Brown Shoe Company was writing the early scripts around modern media celebrity endorsement. Arguably, the American comic strip represented the first truly mass medium of the new century. Via newspaper networks and early syndication, premiere strips like Happy Hooligan, Katzenjammer Kids, Foxy Grandpa and Buster Brown were read on the same day coast to coast, a simultaneous, communal experience. That common content drafted nicely onto the new processes of mass production and distribution in manufacturing. Commodities now needed national identities. Consumer product branding emerged at precisely the time national entertainment heroes emerged in comic strips and soon in movies. The marriage of branding and celebrity seems natural and inevitable in part because they both came from a common source, the nationalization and standardization of both media and consumer goods. Consumer culture was being born, and in Buster Brown Shoes we see one of its weirder contours. Characters could be made into anodyne brands, while inert commodities could be given the gloss of personality.