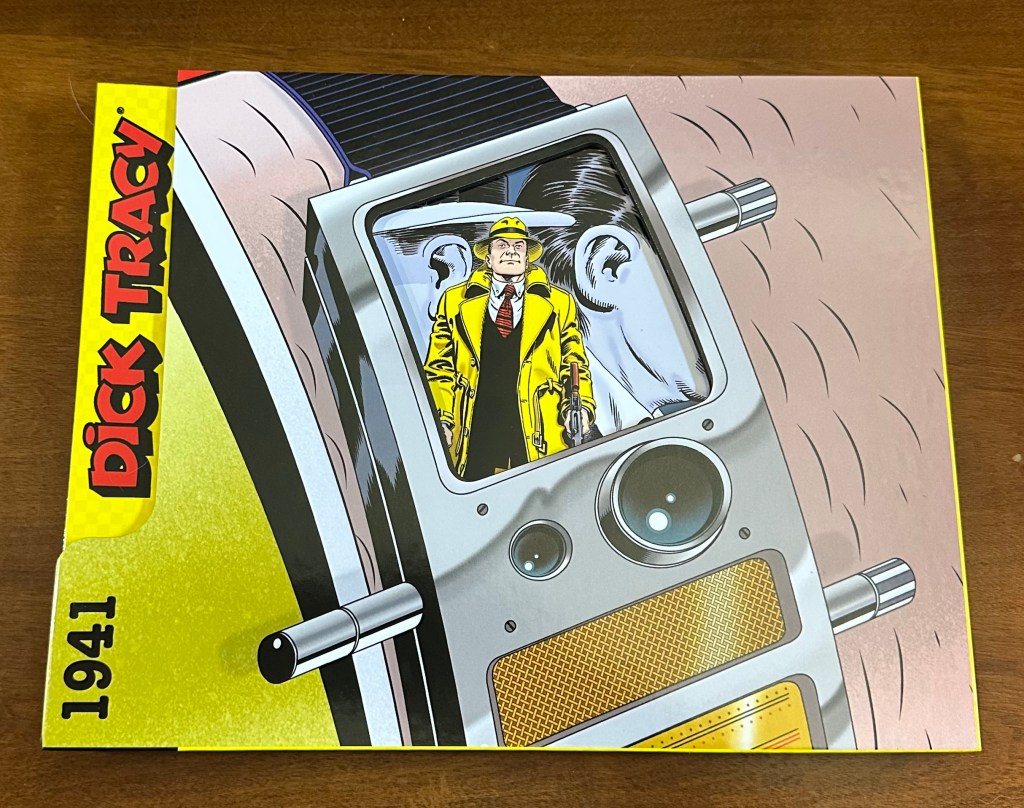

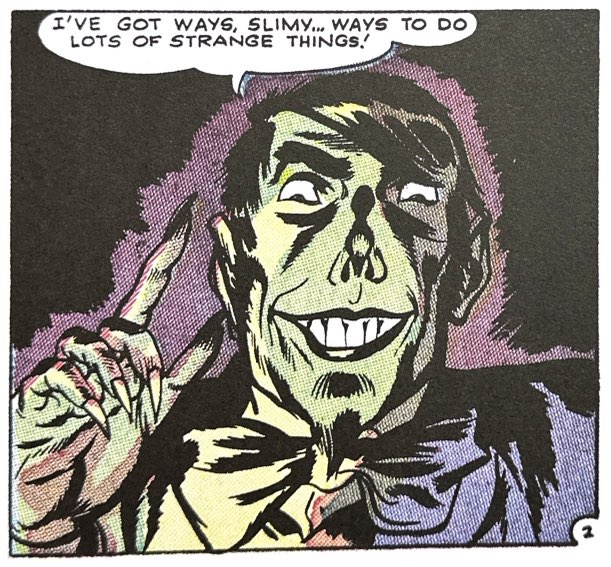

Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy has been among the most reprinted strips of all time. The reasons are obvious, and I don’t need to rehash this site’s exegesis on my personal favorite. Tracy was the strip that turned me on to classic newspaper comics. Gould’s singular visual signature, his grisly violence, grotesque villains and deadpan hero made Dick Tracy compelling on so many levels. And now we get yet another packaging style from the same Library of American Comics group that finished its magisterial 29-volume complete Gould run, 1931-77. With new publishing partner Clover Press, LOAC has reworked some of its earliest projects, like the magnificent upgrade of Terry and the Pirates and the first six volumes of The Complete Dick Tracy. And now we get slipcased, paperback editions of prime-time Gould, 1941 through 1944. Much more affordable, manageable, and available than the original LOAC volumes, each of which covered about two years of comics, the four $29.99 books are also available as a discounted set from Clover. This new series started as a crowd-funded BackerKit project last year.

Continue readingCategory Archives: Reviews

The Year in Pre-Code Comic Book Reprints, 2025

I am an EC chauvinist. I should cop to this before rounding up the notable pre-code comic book reprints from the last year. For decades now I have been devouring the many crime, horror, sci-fi, and romance comics that were part of the glut of adult titles after WWII, in part because they represented the unrealized potential of the comics format in post-war America. This was a real pop culture moment. War veterans ate a steady diet of comic books “over there” and seemed primed to follow the medium into more nuanced and adult storylines in the 40s and 50s. Likewise overseas, Japanese manga and Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées were on a similar path towards the popular, if not literary, mainstream. But in the U.S. that evolution was derailed and slammed into reverse by anti-comics crusades and the industry’s own “Comics Code Authority” in 1954. Self-censorship effectively arrested the medium in pre-adolescence, focused the industry on anodyne morality tales and pubescent fantasies of super-human prowess for at least a couple of decades.

Continue reading2025 Comic Reprints: Rediscovering Lost Classics

We have already reviewed some of the major 2025 comic reprint releases from major publishers: the reissue of Sunday Press’s Society is Nix, the anniversary celebrations of Peanuts, Hagar and Beetle Bailey as well as Cathy, and the resurfacing if Rea Irvin’s The Smythes. But this year saw a number of self-publishers bring back everything from Sky Masters of the Space Patrol to Milt Gross. I wanted to devote one round-up that highlights these laudable efforts and the often-obscure treasures they have unearthed.

Continue readingShelf Scan: Celebrating Peanuts, Beetle Bailey, Hagar and Donald

Before Thanksgiving and the shopping season overcomes us, let’s make sure we start our annual Panels & Prose quick takes on recent books for comic strip fans. The pile of new releases is high and teetering, so let’s break this down into several posts this week and next. Today, we handle the celebratory and anniversary collections involving Peanuts, Hagar, Beetle Baley. For a hands-on look at these books, look for the video “Quick Flip” at the end.

Continue readingReview: A Few Words on Anarchy: “Society Is Nix” Gets Shrunken Yet Enlarged (Updated)

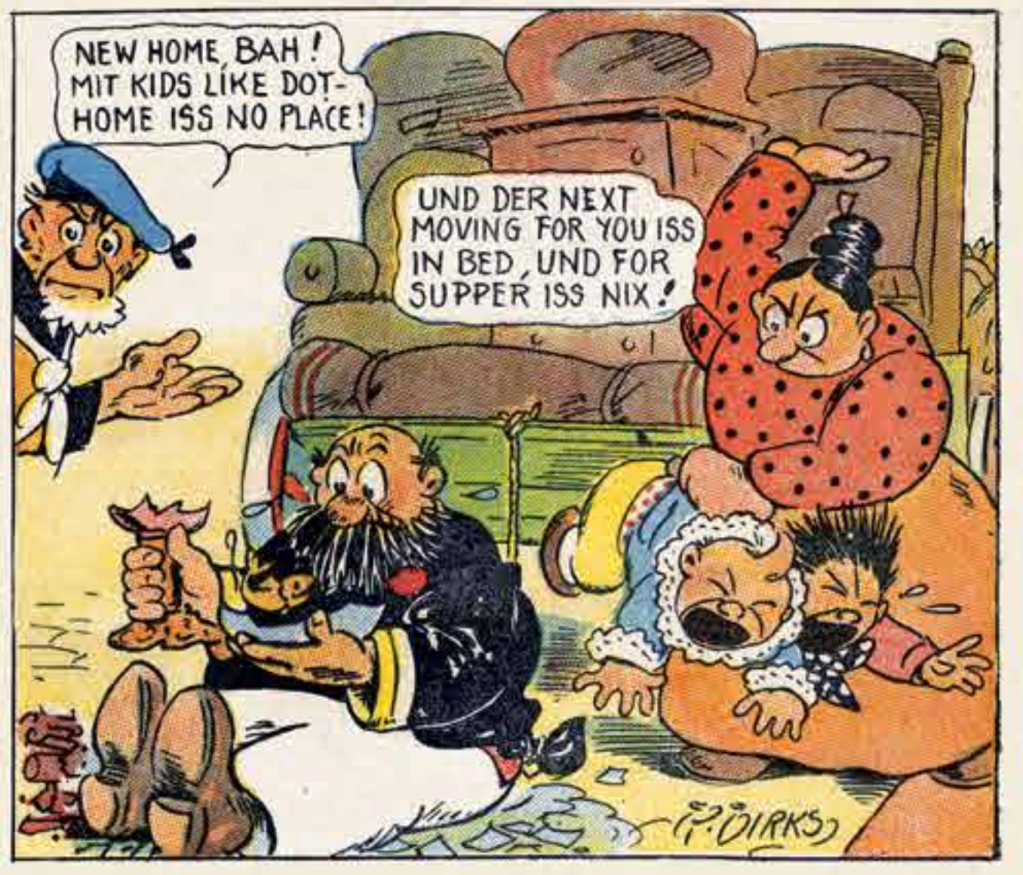

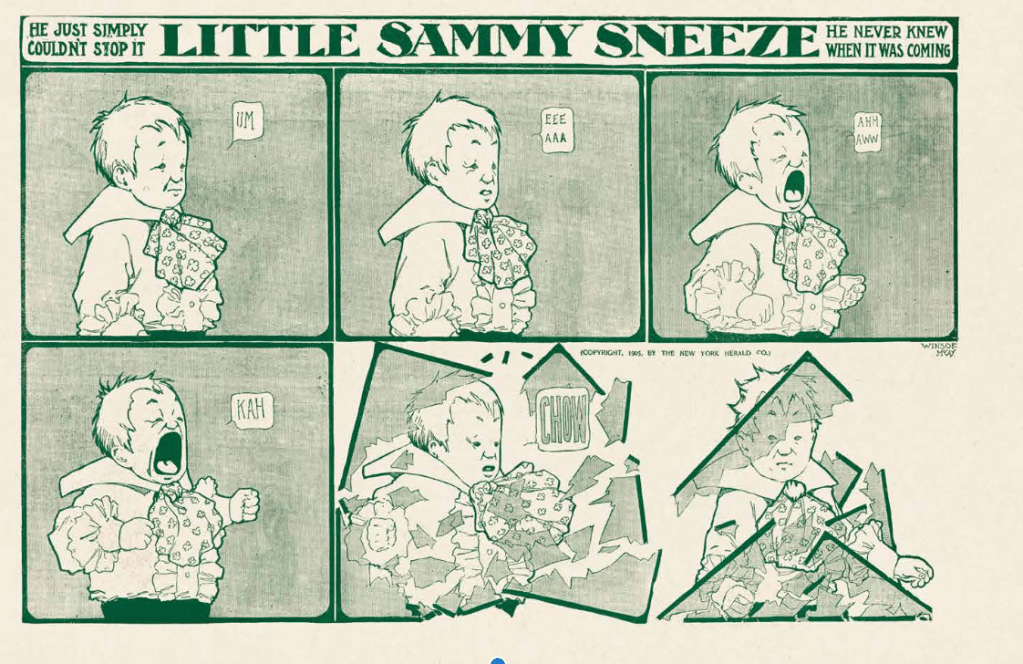

When the massive 21-inch by 17 inch, 152 page slab of early newspaper comic reprints bruised our laps in 2013, Sunday Press’s Society is Nix was a milestone. First of all, we had never seen so many examples from the innovative birthing years of the medium curated so intelligently, restored so beautifully and scaled to the original experience of the first Sunday supplements. Here we got that familiar crumbling mushroom forest in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, but now with the tonal nuance and size McCay intended. The Yellow Kid’s Hogan’s Alley was clear and detailed enough to appreciate all of that background business R.F. Outcault helped pioneer. We could best appreciate the sense of motion, and symmetry of Opper’s signature spinning figures in Happy Hooligan and Her Name Was Maude. And James Swinnerton’s often primitive-seeming linework revealed its expressiveness and intentionality when viewed closer up. Taking its title from a proclamation by the Inspector about the unruly Katzenjammers (“Mit dose kids, society iss nix!”), the book captured the creative freedom of a medium that hadn’t settled yet on a form, let alone a business model. Editor/Restorer Peter Maresca was unrivaled both in his eye for the right exemplary strip as well as his sheer skill in reviving the original color and detail from these yellowed, faded paper. For the last. Decade, Society is Nix remained indispensable for any fan or historian of the medium.

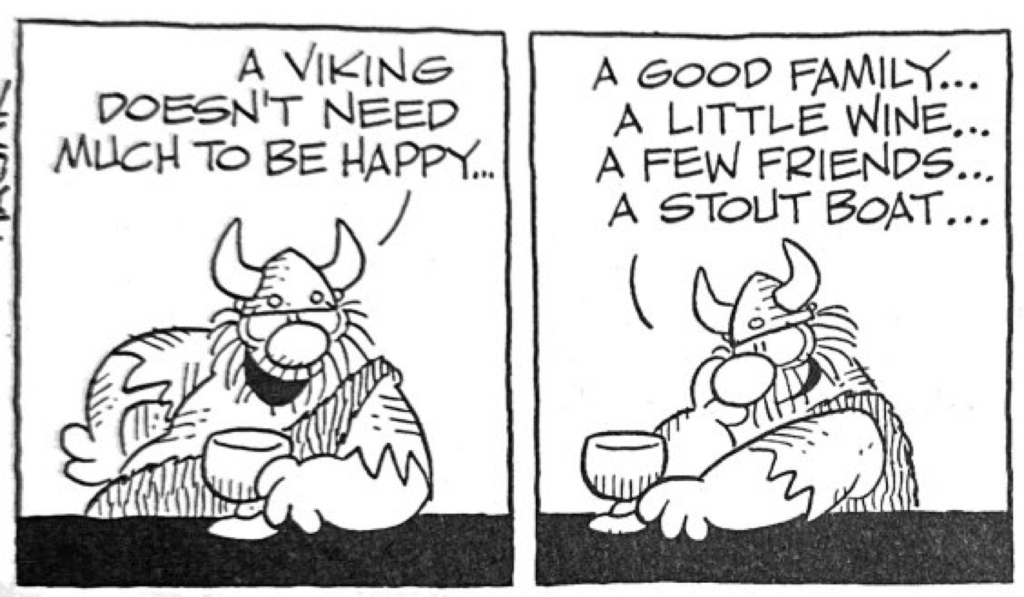

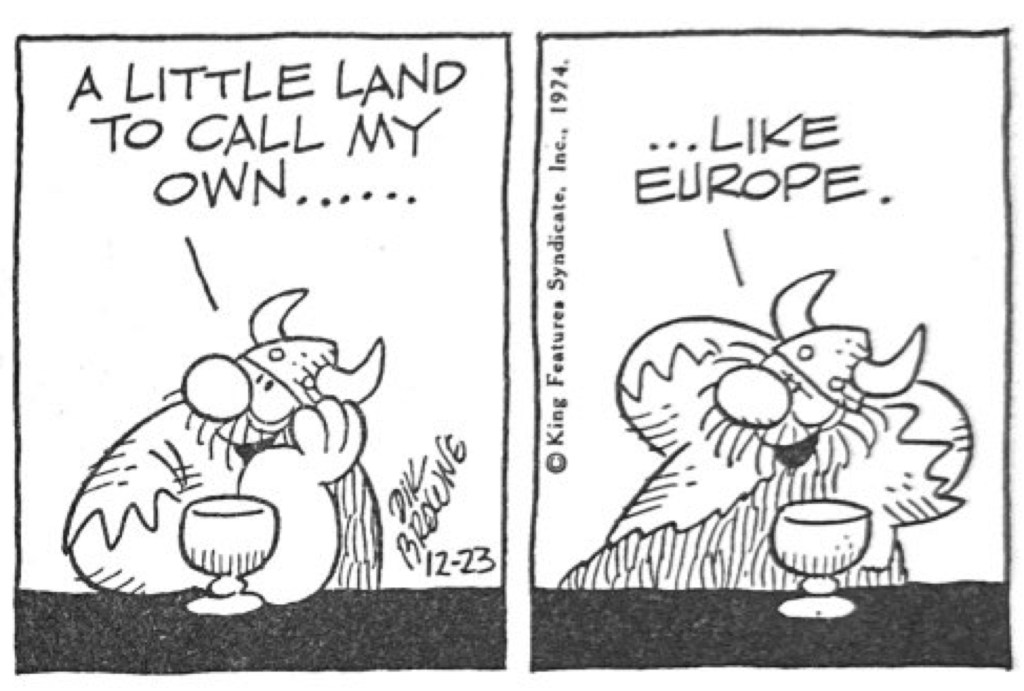

Continue readingThe Daily Anachronism: Fifty Years of Hagar

Like all of the most endearing comic strips. Dik Browne’s Hagar the Horrible came from a personal place. As Dik’s son Chris Browne tells it in the barbarian-sized collection, Hagar the Horrible: The First 50 Years (Titan, $49.99), the Brownes often joked about dad’s beefy, bearded, playfully irascible demeaner as Hagar-like. And it turns out, most of the eventual strip was loosely based on the character types and dynamics of the Browne household.

Continue readingEC Sci-Fi At Scale: Taschen’s XXL Weird Science

The EC science fiction titles hold a special place in American pop culture. The books that ran from 1950 to 1955 (Weird Science, Weird Fantasy, Weird Science-Fantasy) were indispensable waystations for the still-niche genre of science-based speculative fiction. I would argue they were the crucible in which pop sci-fi as we have known it was forged. These comics not only popularized some of the foundational tropes of the genre. But EC’s stable of premiere artists then visualized many of these themes in ways that were far more sophisticated than the typically awful B- and C-level production values Hollywood applied to the sci-fi genre. Even though these comics were among the least popular of the EC titles, they likely were legitimating sci-fi in more young readers’ minds than any pulp mag or film c-lister could. And at the same time, artists like Wally Wood, Al Feldstein, Joe Orlando, Harvey Kurtzman and Jack Kamen were inventing a visual language for sci-fi themes: post-apocalyptic vistas, space travel, the romance of a starship launch, bug-eyed and fish-faced aliens. Their influence on the subsequent conceits of sci-fi fiction, art and film, as well as their look, is undeniable. From Forbidden Planet (1956) to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Star Trek (1966), Star Wars (1977) and beyond, these comics were the first rough sketches of what our fantasies of the future would become.

Continue reading